The ceaseless ebb and flow. A surge forward, followed by a seemingly inevitable retreat. This is the rhythm of the ocean, and, dare I say, a mirror reflecting the multifaceted, often frustrating, history of feminism. Why are we so captivated by this “wave” metaphor? Is it merely a convenient descriptor, or does it tap into something deeper, a primal understanding of power, resistance, and the perpetual struggle against entrenchment? Let’s dismantle this construct, shall we? Let’s excavate the sedimentary layers of feminist history, exposing the fault lines and the points of triumphant upheaval.

The fetishization of the “wave” is insidious. It compartmentalizes, sanitizes, and ultimately, diminishes the complexities of our collective fight. But, alas, we’re stuck with it. So, let’s deconstruct it, shall we?

The Fabled First Wave: Suffrage and the Specter of Domesticity

The First Wave, supposedly, crashes onto the shores of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is a story told through sepia-toned photographs of suffragettes, white women (notice a trend?), demanding the right to vote. A critical victory, undoubtedly. However, to frame this solely as a quest for enfranchisement is a gross oversimplification. It ignores the interwoven threads of abolitionism, temperance, and the burgeoning labor movement, all of which contributed to the era’s ferment of social change. The iconic suffragette, clad in white, becomes a symbol, deliberately curated to project respectability and quell the anxieties of a patriarchal society.

The demand for the vote was inextricably linked to the era’s understanding of women’s roles. Proponents argued that women, by virtue of their inherent moral superiority (a dubious claim in itself!), were uniquely positioned to cleanse the political system of corruption. This argument, while strategically effective, also reinforced the very domestic sphere that limited women’s agency. It was a tightrope walk between challenging the status quo and appeasing its gatekeepers. We needed allies, even if those allies held repugnant opinions about our intrinsic worth.

This wave, then, was a qualified victory, achieving political gains for some, while simultaneously perpetuating existing inequalities. Its legacy is a complex tapestry of progress and compromise.

The Second Wave: Liberation, Revolution, and the Personal as Political

The Second Wave, roaring onto the scene in the 1960s and 70s, was a seismic shift. Fueled by the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-war protests, it challenged not just legal discrimination, but the very fabric of patriarchal society. “The personal is political” became the rallying cry, shattering the illusion of a private sphere untouched by systemic oppression. It was a time of consciousness-raising groups, bra-burning (a myth, mostly), and a radical re-evaluation of gender roles.

Reproductive rights took center stage, with the landmark Roe v. Wade decision offering a hard-won, and perpetually threatened, victory. The focus expanded beyond suffrage to encompass issues of sexuality, domestic violence, workplace equality, and the objectification of women in media. The very language we used was scrutinized, challenged, and ultimately, transformed. “Ms.” replaced “Miss” and “Mrs.,” signaling a woman’s identity independent of her marital status. This seemingly small act was a potent symbol of the Second Wave’s commitment to dismantling patriarchal structures at their root.

But, and there’s always a “but,” the Second Wave was not without its blind spots. Its focus remained largely centered on the experiences of white, middle-class women, often marginalizing the voices of women of color, working-class women, and queer women. The concept of “universal sisterhood” proved to be a fallacy, revealing the uncomfortable truth that even within feminism, power dynamics persist. The wave crashed, leaving behind both significant advancements and unresolved fissures.

The Third Wave: Intersectionality, Riot Grrrls, and the Embrace of Ambiguity

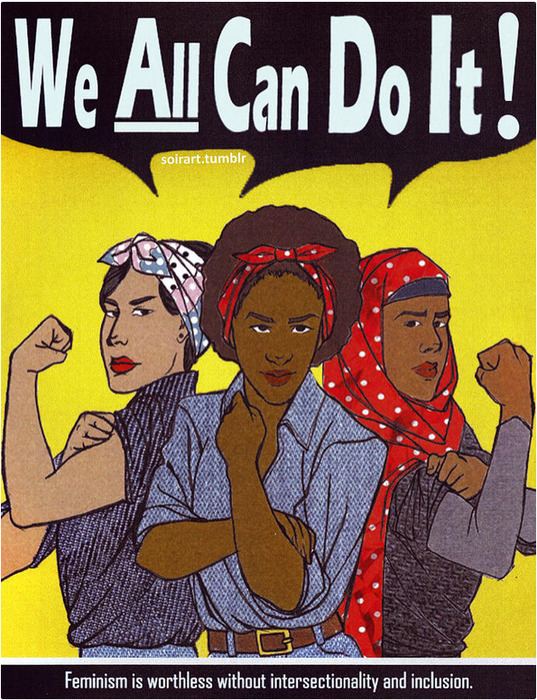

The Third Wave, emerging in the 1990s, was a direct response to the perceived shortcomings of its predecessor. It embraced intersectionality, recognizing that gender oppression is inextricably linked to other forms of discrimination based on race, class, sexuality, and ability. The riot grrrl movement, with its DIY ethos and unapologetically feminist lyrics, provided a soundtrack for a generation of young women rejecting traditional notions of femininity.

This wave celebrated fluidity and challenged binary thinking. There was no longer a singular, prescribed way to be a feminist. Individual expression, personal agency, and the rejection of rigid ideologies became paramount. Zines proliferated, providing a platform for marginalized voices to share their stories and challenge dominant narratives. This emphasis on inclusivity and diversity was a crucial corrective to the Second Wave’s exclusionary tendencies.

However, some critics argued that the Third Wave’s emphasis on individual choice diluted its political focus. The rise of “girl power,” while ostensibly empowering, was often co-opted by corporate interests, transforming feminism into a marketable commodity. The wave, fractured and decentralized, struggled to maintain a cohesive political agenda.

The Fourth Wave: Social Media, Hashtag Activism, and the Hyper-Visibility of Struggle

The Fourth Wave, fueled by the internet and social media, is characterized by its hyper-visibility and global reach. Hashtag activism has become a powerful tool for raising awareness, mobilizing support, and challenging perpetrators of harassment and violence. #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, and #TimesUp are just a few examples of how online platforms have amplified marginalized voices and sparked global conversations about inequality.

This wave is also marked by its focus on online harassment and digital safety. The anonymity of the internet has emboldened perpetrators of cyberbullying, doxxing, and other forms of online abuse. The fight for online spaces that are safe and inclusive for all is a crucial battleground in the Fourth Wave.

But this wave is not without its drawbacks. The echo chambers of social media can reinforce existing biases and limit exposure to diverse perspectives. The performative nature of online activism can also lead to “slacktivism,” where online engagement substitutes for real-world action. The constant barrage of information can be overwhelming, leading to burnout and a sense of hopelessness. The wave is vast and turbulent, its direction often unclear.

Beyond the Waves: A Sea of Constant Change

Perhaps the “wave” metaphor is fundamentally flawed. It suggests a linear progression, a series of distinct periods with clear beginnings and ends. But the reality is far more complex. Feminist struggles are ongoing, overlapping, and interconnected. They are not confined to specific historical moments or geographical locations. They are a constant sea of change, ebbing and flowing, rising and falling, but always present.

We must move beyond the simplistic categorization of “waves” and embrace a more nuanced understanding of feminist history. We must acknowledge the contributions of all women, regardless of their race, class, sexuality, or geographical location. We must be critical of our own biases and strive for inclusivity in all that we do. The fight for gender equality is far from over. It requires a sustained and collective effort, a refusal to be silenced, and a unwavering commitment to justice.

The “wave” metaphor, with all its limitations, reminds us that progress is not always linear. There will be setbacks, defeats, and moments of despair. But the tide will continue to turn. The struggle will continue. And we, as feminists, must continue to rise to meet the challenge, armed with knowledge, courage, and an unwavering belief in the possibility of a more just and equitable world. So, let the ceaseless ferment continue. The revolution, after all, is a marathon, not a sprint.

Leave a Comment