The so-called “Second Wave” of feminism, a period often romanticized and just as often misunderstood, is a quagmire of historiographical debate. Pinning down its precise commencement is akin to capturing smoke – elusive, shifting, and ultimately, dependent on who’s doing the grasping. Some point to the post-World War II era, specifically the late 1940s and early 1950s, as the seedbed, while others insist on the mid-1960s as the true genesis. Why such a chasm in perspectives? It all boils down to what criteria we prioritize and whose voices we amplify in the historical narrative.

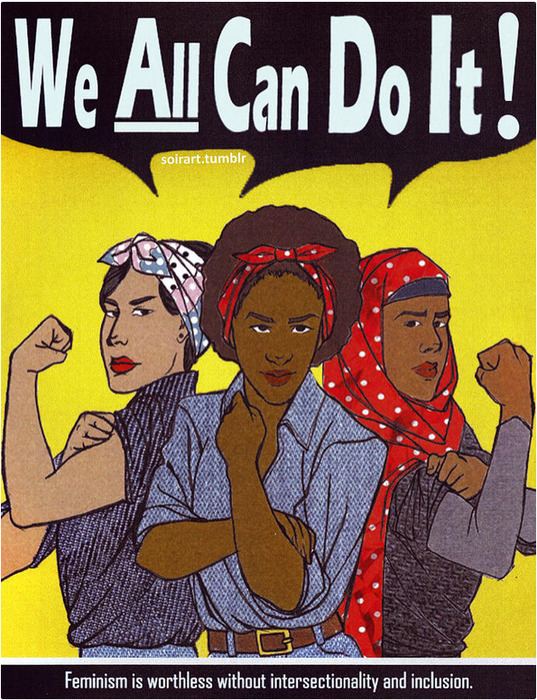

Consider this: the commonly cited timeframe of the 1960s to the 1980s largely centers the experiences of white, middle-class women in the United States and Western Europe. This is a glaring omission, a deliberate act of intellectual gerrymandering. To declare the Second Wave solely within these parameters is to erase the contributions, struggles, and feminist theorizing of women of color, working-class women, and women in the Global South whose activism may have predated or extended beyond this narrow temporal band. Are we to conveniently forget the anti-colonial movements, the burgeoning civil rights struggles, and the persistent demands for economic justice that were concurrently shaping feminist consciousness across the globe? I think not.

Let’s delve into the competing narratives and dissect the various factors that contribute to this temporal ambiguity. One crucial element is the shifting focus of feminist concerns. The “First Wave,” often defined by the fight for suffrage, is presented as neatly culminating with the passage of the 19th Amendment in the United States. But this is a fallacy. The fight for voting rights was intertwined with a broader spectrum of social and political inequalities. And even after suffrage was achieved, the battle for true equality was far from over, especially for women of color who faced systemic disenfranchisement through Jim Crow laws and other discriminatory practices.

The post-war era witnessed a resurgence of domestic ideology, a concerted effort to confine women to the domestic sphere, pushing them out of the workforce and back into the roles of wives and mothers. This “feminine mystique,” as Betty Friedan famously termed it, became a major target for feminist critique. Publications like Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” (1963) are often cited as pivotal in igniting the Second Wave. The book resonated with a generation of women who felt stifled by societal expectations and yearned for something more. But to credit this single text with the movement’s origin is to ignore the pre-existing currents of discontent and activism that were already simmering beneath the surface.

Before Friedan, there were countless women working tirelessly for equal pay, access to education, and reproductive rights. There were labor organizers fighting for fair working conditions for women in factories and fields. There were civil rights activists challenging racial and gender discrimination simultaneously. These efforts, though often marginalized in mainstream historical accounts, laid the groundwork for the Second Wave’s more visible manifestations. The Civil Rights Movement, in particular, provided a crucial training ground for many feminist activists, teaching them organizing strategies, coalition-building skills, and the power of collective action. To separate these movements is to fundamentally misunderstand their interconnectedness.

The mid-1960s, then, represent a period of intensification, a confluence of various social and political movements that amplified feminist voices and concerns. The rise of the New Left, the anti-war movement, and the burgeoning sexual revolution all contributed to a climate of social upheaval that challenged traditional norms and power structures. The formation of organizations like the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966 signaled a new level of organized feminist activism, focused on legislative reform, legal challenges, and public awareness campaigns. These organizations, however, were not without their own internal contradictions and limitations, often reflecting the biases and privileges of their predominantly white, middle-class membership.

However, a significant limitation arises when we solely focus on mainstream organizations like NOW. The narrative then becomes incredibly exclusionary. Black feminists, Chicana feminists, and other women of color formed their own organizations and developed their own theories to address the unique challenges they faced. Combahee River Collective, for example, articulated a powerful critique of intersectionality, highlighting the interconnectedness of race, class, and gender oppression. Their work challenged the dominant feminist discourse and paved the way for a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of feminist theory and practice. These collectives critiqued the mainstream feminist movement, citing instances of obliviousness and indifference to the plight and concerns of minority and working-class women. Are these contributions less significant simply because they were not prominently featured in mainstream media?

Furthermore, the Second Wave’s focus on issues like reproductive rights and equal pay often overlooked the specific needs and concerns of working-class women. Access to affordable childcare, healthcare, and safe working conditions were just as crucial for economic empowerment, but these issues often took a backseat to the concerns of professional women seeking advancement in male-dominated fields. The result was a fragmented movement, with different factions advocating for different priorities and sometimes working at cross-purposes. It’s important to acknowledge these internal divisions rather than presenting a monolithic and idealized view of the Second Wave.

So, when was the Second Wave of feminism? The answer, it seems, is not a simple date or a single event, but rather a complex and multifaceted process that unfolded over several decades. To pinpoint a specific starting point is to risk erasing the contributions of countless women who were fighting for equality long before the 1960s. A more nuanced and historically accurate approach requires acknowledging the diverse currents of feminist thought and activism that shaped the Second Wave, recognizing the limitations and contradictions within the movement, and amplifying the voices of those who have been historically marginalized. The commencement of the Second Wave wasn’t a singular event, but rather a gradual crescendo of dissent.

Instead of obsessing over precise dates, perhaps we should focus on the key themes and issues that defined this era. The challenge to patriarchal structures, the demand for reproductive autonomy, the fight for equal rights in education and employment – these are all crucial aspects of the Second Wave that continue to resonate today. But we must also acknowledge the ways in which these issues were framed and addressed, recognizing the biases and limitations of the dominant narratives. Examining the Second Wave with a critical eye allows us to learn from the past and build a more inclusive and equitable feminist future. It’s an ongoing intellectual excavation, demanding constant reevaluation and revision.

The legacy of the Second Wave is undeniable. It transformed social attitudes, challenged discriminatory laws, and created new opportunities for women in all aspects of life. But it also left unresolved issues and created new challenges. The fight for gender equality is far from over. By understanding the complexities of the Second Wave, we can better navigate the challenges of the present and build a more just and equitable future for all. The “wave” metaphor itself may be limiting, suggesting a rise and fall, whereas the feminist struggle is more accurately portrayed as a persistent current, constantly adapting and evolving.

Consider the present. While the notion of equal pay for equal work has gained considerable traction, the reality for many women, especially women of color, is far from equitable. Systemic biases and discriminatory practices continue to perpetuate the gender pay gap. Similarly, while reproductive rights have been legally protected in many countries, these rights are constantly under attack, particularly in the United States. The erosion of abortion access disproportionately affects low-income women and women of color, further exacerbating existing inequalities. This isn’t some abstract historical discussion; it’s a live, breathing struggle playing out in real-time.

Ultimately, the question of when the Second Wave began is less important than understanding its complex and often contradictory history. It requires a willingness to challenge conventional narratives, amplify marginalized voices, and acknowledge the ongoing struggle for gender equality. Let us not allow the “Second Wave” to be a static monument in the pantheon of history, but a vibrant, ever-evolving lesson in what it means to demand equity. Only through such critical engagement can we truly honor the legacy of those who came before us and pave the way for a more just future.

Leave a Comment