Darling, isn’t it quaint how history loves to neatly package complex sociopolitical upheavals into digestible little stages? As if centuries of struggle, dissent, and radical reimagining can be squeezed into three tidy boxes, each labeled with a cutesy moniker. Can we really capture the unruly, multifaceted beast that is feminism in such a circumscribed framework? Perhaps we can, if we dare to delve into the nuances and challenge the inherent limitations of this periodization.

The truth is, the notion of “three waves” of feminism, while providing a semblance of historical architecture, often glosses over the immense diversity within the movement. It risks homogenizing the experiences of women from various backgrounds, erasing the contributions of marginalized groups, and obscuring the continuities and ruptures that have shaped feminist thought. Still, for the sake of deconstruction, let’s navigate these purported stages, armed with skepticism and a critical eye.

First-Wave Feminism: Suffrage and the Cult of Domesticity’s Demise

Ah, first-wave feminism. Picture it: corsets, suffragette sashes, and a fervent desire to crack open the ballot box. But reducing this era to mere suffrage is a disservice to its complexities. The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a profound interrogation of societal norms and legal structures that relegated women to a subordinate position. It was a time of nascent critiques of patriarchal power, albeit largely framed within the confines of a white, middle-class perspective. Very few black women were involved. The era did little to advance their rights.

The Legal and Political Battlefield:

Suffrage, undeniably, was a cornerstone of the first-wave agenda. Obtaining the right to vote was perceived as a crucial step towards achieving political agency and influencing legislation that directly impacted women’s lives. Visionaries like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton spearheaded the charge, deploying eloquent rhetoric and tireless organizing to challenge the prevailing dogma that women were intellectually inferior and therefore unfit for political participation. But the fight extended beyond the ballot box. First-wave feminists also campaigned for property rights, access to education, and reforms to divorce laws. They sought to dismantle the legal framework that rendered women dependent on men and deprived them of autonomy over their own lives.

Challenging the Cult of Domesticity:

Simultaneously, the movement confronted the insidious “cult of domesticity,” which idealized women as pious, pure, submissive, and domestic. This ideology, deeply embedded in Victorian society, confined women to the private sphere, relegating them to the roles of wife, mother, and homemaker. First-wave feminists challenged this restrictive paradigm, arguing that women were capable of intellectual pursuits, professional careers, and civic engagement beyond the confines of the home. They questioned the notion that a woman’s worth was solely determined by her ability to maintain a flawless household and raise virtuous children. The era was limited. It had a difficult time making traction with non-white women and working-class women.

Limitations and Exclusions:

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge the limitations of first-wave feminism. Its focus was largely on the concerns of white, middle-class women. The movement often failed to address the specific challenges faced by women of color, working-class women, and immigrant women. Racism, classism, and nativism were pervasive within the movement, leading to the marginalization and exclusion of those who did not fit the dominant demographic. The struggle for suffrage, while a significant achievement, often prioritized the enfranchisement of white women over the needs of other marginalized groups.

Second-Wave Feminism: The Personal is Political and the Revolution of the Body

Enter second-wave feminism, a rebellious child born from the social and political ferment of the 1960s and 70s. This era witnessed a radical expansion of feminist discourse, moving beyond legal and political reforms to encompass a broader critique of patriarchal power structures that permeated every aspect of women’s lives. The slogan “the personal is political” became a rallying cry, underscoring the interconnectedness of individual experiences and systemic oppression.

Radical Feminism and the Critique of Patriarchy:

Second-wave feminism saw the rise of radical feminist thought, which posited that patriarchy—a system of male dominance—was the root cause of women’s oppression. Radical feminists challenged traditional gender roles, sexual norms, and power dynamics within intimate relationships. They argued that women’s liberation required a fundamental restructuring of society, dismantling the institutions and ideologies that perpetuated male supremacy. The concept of “consciousness-raising” became a central practice, encouraging women to share their experiences and collectively analyze the ways in which patriarchy operated in their lives. The movement was diverse but not cohesive. It had different goals depending on the particular group.

Reproductive Rights and Bodily Autonomy:

Reproductive rights emerged as a key battleground in the second-wave feminist struggle. Access to contraception and abortion were viewed as essential for women’s control over their own bodies and their ability to participate fully in society. Second-wave feminists challenged restrictive abortion laws, arguing that they violated women’s fundamental right to privacy and bodily autonomy. The landmark Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973, which legalized abortion nationwide, was a significant victory for the movement. The movement did not include enough voices from the queer community.

Challenging Gender Roles in the Workplace and the Home:

Second-wave feminists also tackled gender inequalities in the workplace and the home. They challenged discriminatory hiring practices, wage gaps, and the lack of opportunities for women in traditionally male-dominated fields. They also questioned the division of labor within the household, arguing that women disproportionately bore the burden of childcare and housework. The movement advocated for equal pay, affordable childcare, and a re-evaluation of traditional gender roles in both the public and private spheres. The group was heavily concerned with issues of discrimination.

Internal Divisions and the Rise of Intersectionality:

However, second-wave feminism was not without its internal divisions. Debates raged over issues such as sexuality, pornography, and the role of women in the military. The movement also faced criticism for its lack of inclusivity, particularly its failure to adequately address the experiences of women of color and other marginalized groups. The emergence of intersectionality, a framework that recognizes the interconnectedness of various forms of oppression, challenged the homogenizing tendencies within second-wave feminism and paved the way for a more nuanced understanding of gender inequality.

Third-Wave Feminism: Embracing Complexity and Challenging Essentialism

Then comes third-wave feminism, a child of the 1990s and early 2000s, born into a world shaped by globalization, digital technology, and the rise of multiculturalism. This era represented a conscious effort to move beyond the perceived limitations of second-wave feminism, embracing complexity, challenging essentialist notions of womanhood, and prioritizing individual agency and self-expression.

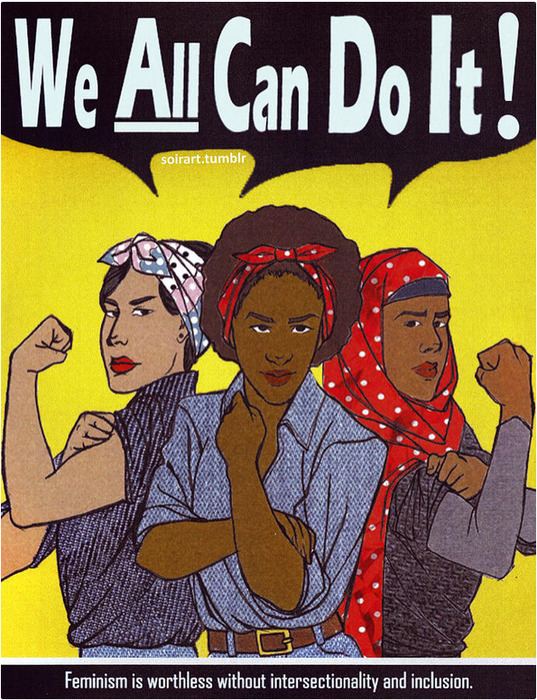

Embracing Diversity and Intersectionality:

Third-wave feminism placed a strong emphasis on diversity and intersectionality. It acknowledged that women’s experiences are shaped by a complex interplay of factors, including race, class, sexuality, disability, and nationality. Third-wave feminists sought to create a more inclusive and representative movement, amplifying the voices of marginalized women and challenging the dominance of white, middle-class perspectives. The wave of activism was much more intersectional than previous waves.

Challenging Essentialism and Embracing Ambiguity:

Third-wave feminism challenged essentialist notions of womanhood, rejecting the idea that there is a single, universal female experience. It embraced ambiguity, recognizing that women have diverse desires, identities, and experiences. Third-wave feminists resisted prescriptive definitions of feminism, arguing that individuals should be free to define their own feminist praxis. The movement was fluid and much more nuanced.

Reclaiming Sexuality and Challenging Rape Culture:

Third-wave feminism reclaimed sexuality as a site of empowerment and agency. It challenged the notion that women’s sexuality should be defined by male desire and advocated for women’s right to explore and express their sexuality on their own terms. Third-wave feminists also confronted rape culture, challenging the normalization of sexual violence and promoting consent and accountability. They sought to create a culture where women felt safe and empowered to assert their boundaries. The wave also began focusing on new societal and cultural issues.

The Role of Technology and Digital Activism:

Third-wave feminism utilized technology and digital media to amplify its message and connect with a wider audience. Blogs, online forums, and social media platforms became important tools for feminist activism, enabling women to share their stories, organize campaigns, and challenge online harassment and misogyny. The digital realm provided new avenues for feminist expression and resistance. This made a lot of organizing easier.

Is There a Fourth Wave?:

The question of whether we are currently in a “fourth wave” of feminism is a subject of ongoing debate. Some argue that the current moment, characterized by the #MeToo movement, increased focus on transgender rights, and the use of social media for activism, constitutes a distinct phase in feminist history. Others maintain that these developments are simply continuations of the themes and concerns that have animated third-wave feminism. Regardless of how we label it, it’s clear that feminism continues to evolve and adapt to the changing social and political landscape. The movement has changed a lot over time.

So, have we managed to neatly package the sprawling, messy saga of feminism into three (or four) easily digestible stages? Of course not. These are merely frameworks, imperfect tools for understanding a movement that defies easy categorization. The real challenge lies in recognizing the nuances, acknowledging the complexities, and celebrating the diverse voices that have shaped and continue to shape the feminist project. The future remains unwritten, and it is up to us to ensure that it is a future where all women can thrive, free from oppression and empowered to realize their full potential. The struggle continues.

Leave a Comment