Alright, sisters, brace yourselves. We’re diving headfirst into the murky, often infuriating, but ultimately triumphant saga of how this whole feminism thing kicked off. Forget the whispers and the revisionist history. We’re going back to the root, to the primal scream that birthed a movement. This isn’t your grandmother’s history lesson; this is a battle cry.

The Seeds of Discontent: A Pre-Feminist Ferment

Before we get to the “official” start, let’s acknowledge the simmering pot of injustice that had been brewing for centuries. The inherent patriarchal structures, the systemic subjugation of women, were not new. What was new was the burgeoning awareness, the nascent articulation of this oppression. Think of it as the tectonic plates of social consciousness beginning to shift. Women, despite being relegated to the domestic sphere, weren’t exactly blissfully ignorant. They felt the iron grip of societal constraints; they just lacked the vocabulary, the platform, and the collective power to effectively challenge it. Let’s face it, the deck was stacked.

Consider the literary salons of the 17th and 18th centuries. These weren’t just tea parties. They were vital spaces where women, often aristocrats or those connected to intellectual circles, could engage in discourse, debate ideas, and, crucially, disseminate subversive thoughts under the guise of polite conversation. These women, often marginalized and silenced, carved out spaces for intellectual rebellion, setting the stage for the more overt activism to come. This groundwork laid the foundation for the arguments that would later be formalized and presented in manifestos and treatises.

Mary Wollstonecraft and the Vindication of Rights: A Clarion Call

And then came Mary Wollstonecraft. The name should be etched into every feminist’s memory. Her 1792 publication, *A Vindication of the Rights of Woman*, was nothing short of a revolutionary manifesto. She didn’t mince words. She eviscerated the notion that women were inherently inferior, arguing instead that their perceived deficiencies stemmed from a deliberate lack of education and opportunity. The patriarchy, she asserted, had strategically kept women ignorant in order to maintain its power. Her work was not just a critique but a potent call for radical social change. She demanded access to education, economic independence, and political representation for women. In essence, she challenged the entire edifice of societal norms, demanding women be recognized as rational, autonomous beings, not mere ornaments or domestic servants.

Wollstonecraft’s arguments, though groundbreaking, weren’t without their limitations. Her focus tended to skew toward middle-class women, inadvertently overlooking the plight of working-class women and those from marginalized communities. Nevertheless, *A Vindication* remains a seminal text, a pivotal moment in the nascent feminist movement. It provided a philosophical framework, a moral imperative, and a roadmap for future generations of activists.

The Abolitionist Connection: A Symbiotic Struggle

The 19th century witnessed a surge in social reform movements, and the fight for women’s rights became inextricably linked with the abolitionist movement. Many early feminists, particularly in the United States, were deeply involved in the fight against slavery. They saw the parallels between the subjugation of enslaved people and the oppression of women. This intersectional consciousness, though imperfect, was crucial in shaping the early feminist agenda.

Women like Sojourner Truth, a former slave and a powerful orator, became vocal advocates for both abolition and women’s rights. Her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, delivered at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, challenged the prevailing notions of womanhood, particularly the exclusion of Black women from the feminist narrative. Truth’s words resonated with an urgency that demanded inclusivity and recognition of the intersectional nature of oppression. This intersectionality, however, faced resistance, with many white suffragists prioritizing their own enfranchisement over the rights of Black women.

The abolitionist movement provided women with valuable organizational and rhetorical skills. They learned how to lobby, organize rallies, and write persuasive arguments. These skills would prove invaluable in the fight for suffrage and other women’s rights issues. The intertwined struggles, however, also exposed the fault lines within the burgeoning movement, revealing the persistent challenges of race and class within the quest for gender equality. The intersection of movements created a powerful force for change, pushing the boundaries of social justice and challenging the status quo in ways that neither movement could have achieved alone.

The Seneca Falls Convention: A Declaration of Independence, Reimagined

1848. Seneca Falls, New York. This is often cited as the official launchpad of the American women’s rights movement. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, along with other activists, organized the first women’s rights convention, attended by around 300 people. The centerpiece of the convention was the “Declaration of Sentiments,” a bold reimagining of the Declaration of Independence. It proclaimed that “all men and women are created equal” and listed a litany of grievances against men, mirroring the complaints leveled against King George III. The audacity!

The Declaration of Sentiments covered a wide range of issues, from property rights and educational opportunities to employment discrimination and the right to vote. While all the resolutions were debated, the most contentious was the demand for suffrage. Many attendees, including Mott, initially thought the idea too radical, fearing it would undermine the credibility of the movement. But Stanton, with her unwavering conviction, persuaded them otherwise. The inclusion of suffrage transformed the convention from a gathering of reform-minded women into a full-fledged political movement. The document was a seismic event that shook the foundations of societal norms and challenged the very definition of citizenship.

The Suffrage Struggle: A Long and Arduous Road

The fight for suffrage became the central focus of the women’s rights movement for the next several decades. It was a long, grueling, and often frustrating struggle, marked by internal divisions, external opposition, and countless setbacks. Suffragists employed a variety of tactics, from peaceful lobbying and petitioning to more militant forms of protest, such as picketing, civil disobedience, and even hunger strikes. They faced ridicule, arrest, and violence. But they persisted.

Organizations like the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, advocated for suffrage at the state and federal levels. The NWSA took a broader approach, addressing a wider range of women’s rights issues, while the AWSA focused primarily on suffrage. These tactical differences, though sometimes divisive, ultimately contributed to the movement’s overall effectiveness. The diversity of strategies allowed for a multi-pronged approach that pressured lawmakers and the public from various angles.

The suffrage movement also faced significant internal challenges, particularly regarding race. While some white suffragists, like Anthony, initially supported Black women’s suffrage, many others prioritized the enfranchisement of white women, often at the expense of Black women’s rights. This betrayal led to the formation of organizations like the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which advocated for both women’s suffrage and racial equality. The struggle for suffrage was far from a monolithic effort; it was a complex tapestry of diverse voices, conflicting priorities, and persistent inequalities. The journey towards enfranchisement highlighted the ongoing need for intersectional awareness and the importance of addressing the specific needs of marginalized communities within the broader feminist agenda.

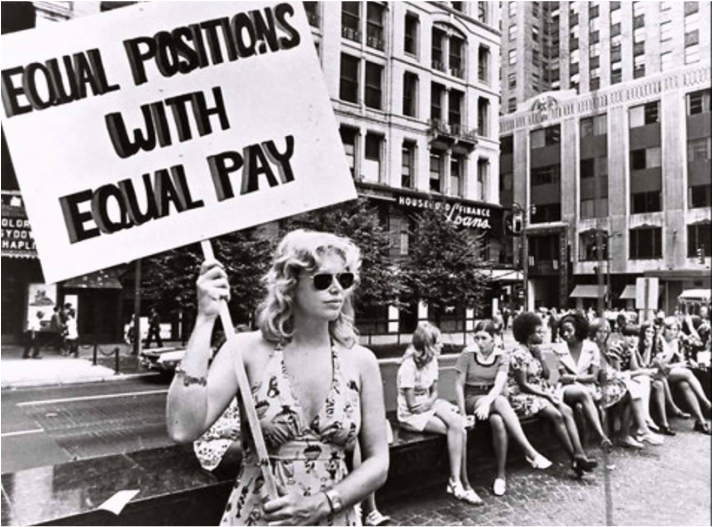

Beyond Suffrage: Laying the Groundwork for Second-Wave Feminism

While suffrage was a monumental achievement, it was not the end of the feminist struggle. In fact, it was just the beginning. The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 marked a significant victory, but it also revealed the limitations of focusing solely on political rights. Women still faced discrimination in education, employment, and reproductive healthcare. The fight for economic equality, reproductive autonomy, and an end to gender-based violence was far from over. The groundwork laid by the early feminists paved the way for the second-wave feminism of the 1960s and 1970s, which would tackle these issues head-on. The seeds of discontent, planted centuries earlier, had finally blossomed into a full-fledged revolution. The fight continues, sisters. The fight always continues.

Leave a Comment