So, here we are, still battling the same old patriarchal dragons. Only now, instead of swords, we’re armed with… dialectical materialism? The question that keeps me up at night, swirling around like a particularly potent cocktail, is this: Can Marxism, a framework forged in the fiery heart of industrial capitalism, truly liberate women? Or is it just another boys’ club, albeit one with slightly better vocabulary and a penchant for overthrowing regimes? Let’s dive in, shall we, and dismantle this historical behemoth piece by infuriating piece.

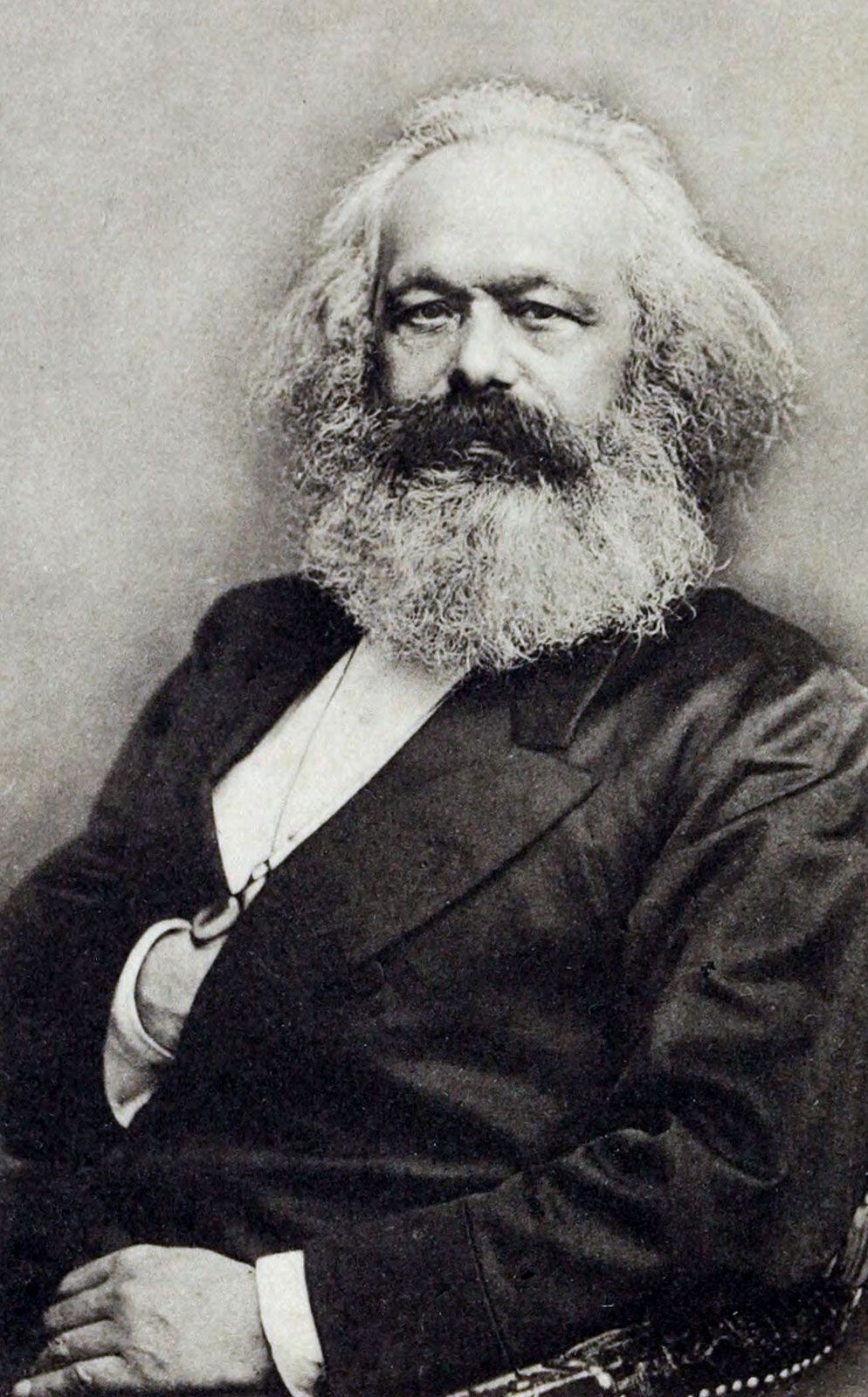

The Foundational Fracture: Marx and the Woman Question

Let’s be clear, Marx himself wasn’t exactly a proto-feminist icon. His analysis, groundbreaking as it was, largely relegated women to the domestic sphere. The labor movement in his time was often as mysoginistic as it was progressive. He viewed them primarily as reproducers of the proletariat, churning out future generations of wage slaves. Not exactly the most inspiring vision, is it? While he recognized the oppression inherent in the capitalist system, he often failed to fully grasp the specificity of women’s subjugation within it. This is what constitutes the “foundational fracture,” a critical gap in the original Marxist framework that later feminist thinkers would attempt to bridge. The early labor movement was a sausage fest, and its male comrades would be slow to accept women’s active participation in the workforce, especially considering their limited reproductive rights.

Engels’ Attempted Amends: “The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State”

Enter Friedrich Engels, Marx’s indispensable partner in crime and intellectual co-conspirator. In “The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State,” Engels attempted to rectify this oversight, arguing that the oppression of women stemmed from the rise of private property and the patriarchal family structure it engendered. He posited that pre-class societies were characterized by a relative equality between the sexes, which was eroded with the development of agriculture and the subsequent accumulation of wealth. This work, a valiant effort, nonetheless suffers from its own limitations. It tends to reduce women’s oppression to an economic phenomenon, neglecting the complex interplay of cultural, ideological, and psychological factors that contribute to their subjugation. Moreover, Engels falls prey to a certain evolutionary determinism, suggesting a linear progression from matriarchy to patriarchy that has been largely debunked by anthropological research. The material conditions are not the only important factors. The cultural conditions and shared social values are also important.

The First Wave: Socialist Feminists and the Battle for Suffrage

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the emergence of socialist feminism, a vibrant movement that sought to integrate Marxist analysis with feminist concerns. Figures like Clara Zetkin and Alexandra Kollontai recognized the limitations of both mainstream feminism, which often focused solely on legal and political rights, and orthodox Marxism, which tended to overlook the specific oppression of women. These women understood that capitalism and patriarchy were mutually reinforcing systems, and that true liberation required a revolutionary transformation of both. They advocated for women’s suffrage, equal pay, access to education, and an end to discriminatory labor practices. They understood that a purely legalistic approach to social change would not be enough, that it would be necessary to address the material conditions of women and their roles in the workforce. Their contributions were indispensable to the burgeoning movement.

The Second Wave: Radicals, Revolutionaries, and the Re-Evaluation of Labor

The second wave of feminism, which exploded onto the scene in the 1960s and 70s, brought with it a renewed engagement with Marxist thought. Radical feminists, while often critical of Marxism’s perceived sexism, nonetheless drew upon its insights into power dynamics and social structures. They expanded the concept of “labor” to include unwaged domestic work, arguing that women’s unpaid contributions to the household were essential to the reproduction of the capitalist system. This “domestic labor debate” sparked fierce controversy but ultimately forced Marxist thinkers to confront the hidden costs of capitalism and the ways in which women’s unpaid work subsidized the economy. Furthermore, second-wave feminists challenged the traditional Marxist focus on class as the primary axis of oppression, arguing that gender, race, and sexuality were equally important categories of analysis. These intersectional insights challenged some of the orthodoxy of the time.

The Rise of Intersectionality: A New Paradigm for Understanding Oppression

The concept of intersectionality, developed by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, has become a cornerstone of contemporary feminist thought. Intersectionality recognizes that individuals experience oppression based on the intersection of multiple social categories, such as race, gender, class, and sexuality. This framework allows us to understand how the experiences of a Black working-class woman, for example, differ significantly from those of a white middle-class woman or a Black working-class man. It challenges the tendency to view oppression as a monolithic phenomenon and highlights the importance of addressing the specific needs and concerns of marginalized groups. Intersectionality compels us to consider a panoply of influences on any individual’s life, and the particular form of struggle they may face.

Beyond the Wage: The Gendered Division of Labor and the Reproduction of Inequality

A key area where Marxism and feminism intersect is in the analysis of the gendered division of labor. Even in societies that have achieved a degree of formal equality, women continue to bear the brunt of domestic work, childcare, and elder care. This unpaid labor not only limits their opportunities for economic advancement but also reinforces traditional gender roles and expectations. Moreover, women are often concentrated in low-paying, precarious jobs with limited benefits, making them particularly vulnerable to economic exploitation. Addressing the gendered division of labor requires not only policies that promote equal pay and access to employment but also a fundamental rethinking of the value we place on care work and the social infrastructure that supports it. The notion of meritocracy is often used as justification, but it ignores the material inequalities that impact women and minorities. It becomes nothing more than a smokescreen.

The State, Sexuality, and the Specter of Reproductive Justice

The Marxist feminist perspective also sheds light on the role of the state in regulating sexuality and reproduction. Throughout history, states have sought to control women’s bodies and reproductive capacities, often in the service of nationalist or economic agendas. From forced sterilization to restrictive abortion laws, women’s reproductive rights have been consistently under attack. Marxist feminists argue that reproductive justice is not simply a matter of individual choice but a fundamental aspect of social and economic equality. Access to abortion, contraception, and quality healthcare is essential for women to control their own lives and participate fully in society. It’s time to stop telling women what to do with their own bodies and respect them as autonomous and free individuals.

Capitalism’s New Clothes: Neoliberalism and the Commodification of Feminism

In recent decades, neoliberalism has posed a new challenge to feminist movements. The rise of free markets, deregulation, and privatization has exacerbated economic inequality and undermined social safety nets, disproportionately affecting women. Moreover, neoliberal ideology has co-opted feminist language and imagery to promote individualistic notions of empowerment and self-reliance. This “commodity feminism” celebrates female CEOs and girlbosses while ignoring the systemic barriers that prevent most women from achieving economic success. It’s a cynical attempt to repackage capitalism as a feminist project, obscuring the inherent contradictions between profit maximization and social justice. This kind of posturing does not move society forward. It simply allows the wealthy and powerful to amass more wealth and power.

The Future of Feminist Marxism: Solidarity, Strategy, and the Specter of Revolution

So, where does this leave us? Is a synthesis of Marxism and feminism still possible, or are they fundamentally incompatible projects? I would argue that a critical engagement with both traditions remains essential for understanding and challenging the multifaceted oppression of women. By integrating Marxist insights into the dynamics of class and capital with feminist analyses of gender, sexuality, and the body, we can develop a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the forces that shape our lives. More importantly, we can build a more effective movement for social transformation, one that prioritizes solidarity, intersectionality, and a commitment to dismantling all forms of oppression. The question is not whether a feminist Marxism is possible, but whether we have the courage and vision to create it. It will not be easy. Our enemies are powerful, but so are we.

Ultimately, the task before us is to forge a new radical and transformative vision. A vision of true liberation that is neither purely Marxist nor purely feminist, but something altogether new, something more powerful. Because, let’s be honest, the revolution won’t be televised. It will be intersectional, it will be queer, and it will be led by the women who have always been on the front lines, fighting for a world where everyone is truly free. The time for half measures is over. It is time to reclaim our power and build a world that is fair and just for all.

Leave a Comment