Forget the sugar-coated narratives. Let’s delve into the unvarnished truth: feminism, a tapestry woven with threads of defiance, resilience, and unwavering conviction, has been a relentless struggle for autonomy. It’s not a linear progression, a neat ascent toward equality. Instead, it’s a jagged climb, fraught with setbacks, betrayals, and the constant recalibration of strategies. Prepare to have your assumptions challenged.

I. Seeds of Discontent: Pre-18th Century Murmurs of Resistance

The notion that women’s subjugation is a modern phenomenon is a convenient fiction. Long before the Enlightenment, sparks of rebellion flickered in the margins of patriarchal societies. Think of Hypatia of Alexandria, a Neoplatonist philosopher whose intellectual prowess threatened the established order and led to her brutal murder. Or consider the Beguines, semi-monastic communities of women in medieval Europe who carved out spaces for independent living and intellectual pursuits, challenging the Church’s control over female lives. These weren’t organized movements, not in the modern sense. But they represent crucial pre-feminist rumblings, whispers of dissatisfaction that foreshadowed the storm to come. These are the forgotten forerunners, the individuals who dared to question the divinely ordained hierarchy that relegated women to a subordinate position. Even in religious contexts, figures like Hildegard of Bingen utilized visionary experiences and profound writing to carve out spaces of authority. How dare they? Her audacity echoes across the centuries.

II. The Enlightenment’s Paradox: Liberty and Equality… For Whom?

The Enlightenment, that lauded era of reason and progress, proclaimed liberty and equality as universal rights. But universal, it turned out, meant “for men.” This hypocrisy ignited the first major wave of feminist thought. Mary Wollstonecraft, a beacon of intellectual courage, shattered the prevailing narrative of female inferiority with her seminal work, *A Vindication of the Rights of Woman*. She argued, with biting precision, that women’s perceived intellectual limitations were a product of their limited education and social constraints, not inherent deficiencies. Her voice was a clarion call, demanding access to education and political participation. This was not merely about bettering individual lives; it was about transforming the very fabric of society. However, progress was slow, fiercely resisted by those clinging to the old order. The French Revolution, while promising liberation, ultimately sidelined women’s demands for equal rights, demonstrating the deep-seated misogyny that even revolutionary fervor couldn’t eradicate. A bittersweet taste of freedom, indeed.

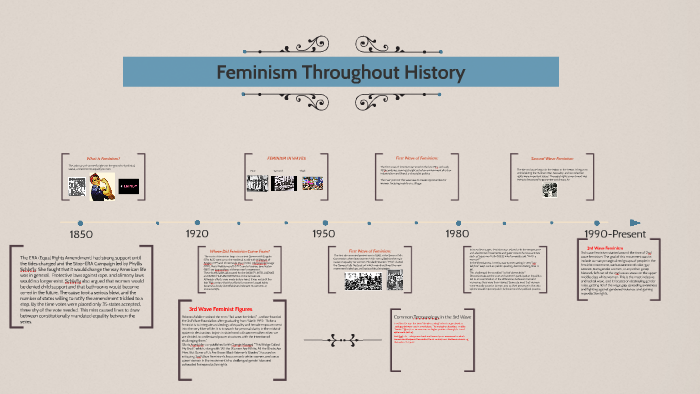

III. The First Wave: Suffrage and Beyond (19th-Early 20th Century)

The 19th century witnessed the emergence of organized feminist movements, primarily focused on securing the right to vote. Suffrage became the rallying cry, the symbol of women’s political agency. Think of the militant tactics of the suffragettes in Britain, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, who embraced civil disobedience and direct action to force the government to take their demands seriously. It was a strategic disruption, a deliberate challenge to the status quo. The Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, a watershed moment in the American women’s rights movement, produced the Declaration of Sentiments, a bold manifesto that called for equal rights in all spheres of life, from property ownership to education. But the fight for suffrage was not monolithic. Internal divisions emerged, particularly around race and class. White suffragists often excluded Black women from their organizations, perpetuating the very inequalities they claimed to oppose. This exclusionary practice reveals the complexities of intersectionality that would gain more prominence in later waves of feminism. Even within the pursuit of a single goal, the seeds of internal conflict were sown.

IV. Interwar Lull and the Rise of the “New Woman”: A False Dawn?

The achievement of suffrage in many Western countries in the early 20th century was hailed as a major victory. But the euphoria was short-lived. The interwar period saw a shift in focus, with the rise of the “New Woman,” characterized by her increased independence and participation in public life. Flapper culture, with its rejection of Victorian norms, symbolized this newfound freedom. However, this image was often superficial, masking the persistent inequalities that remained. Women continued to face discrimination in the workplace, and their roles were still largely confined to the domestic sphere. The gains were tenuous, easily reversible. It was a period of apparent progress, undercut by the insidious persistence of patriarchal structures. This era served as a stark reminder: legal rights alone do not guarantee true equality. A deeper societal transformation was needed.

V. The Second Wave: Liberation and Radicalism (1960s-1980s)

The 1960s witnessed a resurgence of feminist activism, fueled by the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-war protests. The Second Wave broadened the feminist agenda, challenging not only legal and political inequalities but also deeply ingrained cultural norms and attitudes. “The personal is political” became the defining slogan, highlighting the interconnectedness of individual experiences and broader social structures. Issues such as reproductive rights, domestic violence, and sexual harassment gained prominence. Think of Betty Friedan’s *The Feminine Mystique*, which exposed the widespread dissatisfaction among middle-class housewives, trapped in the confines of domesticity. Or consider the radical feminist collectives that emerged, advocating for fundamental social change. This wave was marked by its diversity of perspectives, from liberal feminists who sought to reform existing institutions to radical feminists who called for a complete dismantling of patriarchy. The rise of intersectionality, acknowledging the interconnectedness of gender with other forms of oppression, such as race, class, and sexuality, further complicated the landscape. The Second Wave was a period of intense intellectual ferment, challenging the very foundations of Western society. The battles fought then continue to resonate today.

VI. Backlash and Consolidation: The 1980s and 1990s

The gains of the Second Wave were met with a fierce backlash in the 1980s, as conservative forces mobilized to roll back feminist advances. The rise of the New Right and the Reagan administration in the United States marked a shift toward traditional family values and a resistance to feminist demands. The concept of “post-feminism” emerged, suggesting that feminism was no longer necessary. This was a calculated move, designed to undermine the movement’s credibility and discourage activism. However, feminism did not disappear. Instead, it adapted and evolved. The 1990s saw the emergence of Third Wave feminism, characterized by its emphasis on individualism, cultural diversity, and the reclamation of traditionally feminine symbols. Riot Grrrl, a punk rock feminist movement, provided a powerful voice for young women, challenging patriarchal norms through music and activism. This period was characterized by a more nuanced understanding of power and a greater willingness to engage with popular culture. The battles shifted, becoming more subtle, more insidious. The opposition regrouped, and so did the movement.

VII. The Digital Age and Beyond: Intersectional Feminism in the 21st Century

The internet has revolutionized feminist activism in the 21st century. Social media platforms have provided new avenues for communication, organizing, and mobilizing. The #MeToo movement, which exposed widespread sexual harassment and assault, demonstrated the power of online activism to effect real change. Fourth Wave feminism is characterized by its focus on intersectionality, its embrace of technology, and its commitment to addressing global issues. Transgender rights, environmental justice, and economic inequality have become central concerns. This wave is characterized by a global consciousness, recognizing the interconnectedness of struggles for justice around the world. The digital age has amplified voices that were previously marginalized, creating a more inclusive and diverse feminist movement. But the digital landscape also presents new challenges, including online harassment and the spread of misinformation. The fight for equality continues, now waged on a global scale, in the digital realm and beyond. This new era of feminism is nothing if not interconnected and digitally driven.

VIII. Unfinished Business: The Persistent Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the significant progress that has been made, feminism still has much work to do. Gender inequality persists in all spheres of life, from the workplace to politics to the home. Women continue to face discrimination, harassment, and violence. The gender pay gap remains stubbornly persistent, and women are still underrepresented in positions of power. The challenge now is to address the root causes of these inequalities and to create a more just and equitable society for all. This requires a multi-pronged approach, including legal reforms, cultural shifts, and individual actions. The future of feminism depends on its ability to adapt to changing circumstances and to embrace new perspectives. It requires a commitment to intersectionality, a willingness to challenge power structures, and an unwavering belief in the possibility of a better world. The journey is far from over. The fight continues, demanding constant vigilance and unwavering commitment. The future of feminism hinges on our ability to learn from the past, adapt to the present, and envision a future where true equality reigns supreme. The tapestry of feminism remains unfinished, its threads waiting to be woven into a more vibrant and equitable design. Let us continue to weave.

Leave a Comment