The hallowed halls of international relations, traditionally a boys’ club reeking of testosterone and strategic posturing, have long ignored a fundamental truth: gender isn’t some fluffy, extraneous variable. It’s the damn architecture upon which the entire edifice of global power is built. To ignore it is to fundamentally misunderstand the game, the players, and the stakes. We’re not talking about adding a few female faces to the negotiating table and patting ourselves on the back for inclusivity. We’re demanding a paradigm shift, a seismic reassessment of everything we thought we knew about how the world works. Prepare to have your assumptions demolished.

For too long, mainstream international relations theory has operated under the delusion of a “gender-neutral” framework. This is, quite frankly, a load of patriarchal poppycock. The very concepts of power, security, and the state are imbued with deeply ingrained masculine biases. Realism, with its emphasis on rational actors and the relentless pursuit of national interest, conveniently overlooks the gendered dimensions of these pursuits. Consider, for a moment, the military-industrial complex, that behemoth of destruction and profit. It thrives on a hyper-masculine culture of aggression and dominance, reinforcing traditional gender roles and perpetuating cycles of violence.

Liberalism, with its focus on cooperation and international institutions, fares little better. While it may advocate for women’s rights in certain contexts, it often fails to address the systemic inequalities that underpin the global order. The “free market,” for example, often exacerbates gender disparities, particularly in developing countries where women are disproportionately employed in precarious and low-paying jobs. The very idea of a level playing field is a myth when the rules of the game are rigged from the outset.

So, where do we begin to dismantle this deeply entrenched system of patriarchal power? We start by deconstructing the dominant narratives and exposing the gendered assumptions that underpin them. We need to move beyond simply acknowledging the existence of women and start analyzing the ways in which gender shapes every aspect of international politics. This requires a multi-faceted approach, a radical reimagining of the discipline from the ground up.

I. The Gendered Construction of the State: A Phallogocentric Illusion

The state, that supposedly objective and impartial arbiter of power, is anything but. Its very foundation is built upon a gendered division of labor, both in the domestic and international spheres. The traditional model of the state, with its emphasis on territorial sovereignty and military might, is inherently masculine. Think of the imagery associated with the state: flags, anthems, soldiers – all symbols of strength, dominance, and control, all traditionally associated with masculinity. But this is a deceptive facade, a carefully constructed phallogocentric illusion designed to mask the underlying inequalities and power dynamics.

A. The Dichotomy of Public vs. Private: Silencing the Feminine

The rigid separation of the public and private spheres is a cornerstone of patriarchal ideology. The public sphere, the realm of politics and power, is traditionally associated with men, while the private sphere, the realm of the home and family, is relegated to women. This division serves to silence women’s voices and exclude them from the decision-making processes that shape their lives. It reinforces the idea that women’s concerns are somehow separate from and less important than the “real” issues of international politics. This needs to change.

B. The State as Protector: A Gendered Contract

The state often presents itself as the protector of its citizens, particularly women and children, from external threats. However, this “protection” is often contingent on women’s subordination to the state and its patriarchal structures. Women are expected to support the state’s agenda, including its military endeavors, and to uphold traditional gender roles in the name of national security. This is a deeply problematic dynamic, one that reinforces women’s vulnerability and undermines their agency.

II. Gender and Security: Beyond the Battlefield

The traditional understanding of security, focused on military might and territorial integrity, is woefully inadequate. Security is not simply the absence of war; it’s the presence of safety, well-being, and justice for all. This requires a broader, more inclusive understanding of security that takes into account the gendered dimensions of violence, poverty, and environmental degradation. The narrow focus on state-centric security often ignores the everyday insecurities faced by women around the world.

A. The Continuum of Violence: From Domestic Abuse to War Crimes

Violence against women is not a separate issue from international politics; it’s intimately connected. The same patriarchal attitudes and power dynamics that fuel domestic abuse also contribute to war crimes and other forms of gender-based violence in conflict zones. Rape, sexual slavery, and forced pregnancy are used as weapons of war, targeting women’s bodies and undermining their communities. To ignore this is to perpetuate the cycle of violence.

B. The Gendered Impacts of War: Beyond the Body Count

War affects men and women differently. While men are more likely to be on the front lines, women often bear the brunt of the humanitarian consequences of conflict. They are more likely to be displaced, to experience food insecurity, and to be subjected to sexual violence. They also often become the primary caregivers for children and the elderly, struggling to rebuild their lives in the aftermath of war. The trauma and displacement experienced by women in conflict zones have long-lasting repercussions on their health, well-being, and economic security.

III. Gender and the Global Economy: Exploitation and Empowerment

The global economy is not gender-neutral. It is shaped by patriarchal structures and biases that disadvantage women and reinforce their economic vulnerability. Women are disproportionately employed in low-paying, precarious jobs, often in the informal sector, with little or no access to social protection. They also face discrimination in hiring, promotion, and pay, and are often excluded from leadership positions.

A. The Feminization of Labor: A Race to the Bottom

The increasing feminization of labor in the global economy has led to a “race to the bottom,” with companies seeking to exploit cheap female labor in developing countries. Women are often subjected to exploitative working conditions, including long hours, low wages, and unsafe environments. This is not simply a matter of economic necessity; it’s a deliberate strategy to maximize profits at the expense of women’s well-being.

B. Microfinance and Empowerment: A Double-Edged Sword

Microfinance has been touted as a tool for empowering women in developing countries, providing them with access to credit and enabling them to start their own businesses. However, microfinance can also have negative consequences, trapping women in debt and exacerbating their economic vulnerability. It’s crucial to ensure that microfinance programs are designed to meet the specific needs of women and that they are accompanied by other support services, such as training and education.

IV. Reimagining International Politics: Towards a Feminist Future

A feminist approach to international politics is not simply about adding women to the existing system; it’s about transforming the system itself. It requires a fundamental rethinking of the concepts of power, security, and the state, and a commitment to creating a more just and equitable world for all. It necessitates a move away from the narrow, state-centric focus of traditional international relations theory and towards a more inclusive, people-centered approach.

A. Challenging the Dominant Narratives: Amplifying Marginalized Voices

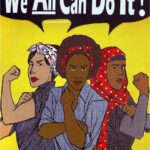

One of the key tasks of feminist international relations is to challenge the dominant narratives that perpetuate patriarchal power structures. This involves amplifying the voices of marginalized groups, including women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ individuals, and bringing their experiences and perspectives to the forefront. It also requires deconstructing the myths and stereotypes that are used to justify inequality and oppression.

B. Building Solidarity and Collective Action: A Global Sisterhood

A feminist future requires building solidarity and collective action across borders. This involves connecting women’s movements around the world and working together to challenge patriarchal power structures at the local, national, and international levels. It also requires building alliances with other social justice movements, such as environmental justice and anti-racism movements, to create a more comprehensive and intersectional approach to social change. It is in unity that our true power resides.

The path towards a feminist international politics will be long and arduous. But it is a path worth fighting for. The stakes are too high to continue down the same road, a road paved with inequality, violence, and oppression. We must embrace a new vision, a vision of a world where gender equality is not just a slogan, but a reality. A world where power is shared, not hoarded. A world where peace is not just the absence of war, but the presence of justice. The future of international politics, and indeed the future of the world, depends on it.

Leave a Comment