Honey, does the patriarchy wear Prada? A frivolous query, perhaps, but it underscores a salient point: power, even patriarchal power, often masquerades behind alluring facades, demanding a discerning eye to unveil its machinations. Feminism, when wielded as a critical theory, becomes that eye, a tool to dissect the pervasive and insidious ways gender shapes – and often constrains – our lives.

To approach feminism as a critical theory is to move beyond simplistic notions of equality and delve into the intricate architecture of power relations. It’s not merely about equal pay for equal work, although that remains crucial. It’s about understanding why women are systematically undervalued in the workforce in the first place. It’s about dismantling the entire edifice of patriarchal privilege, brick by excruciating brick.

Let’s break this down, shall we? Our journey will proceed through the following stages:

I. Genesis of Critique: Tracing Feminism’s Theoretical Roots

A. The First Wave: Suffrage and its Discontents. Focusing primarily on legal and political rights, the first wave, while groundbreaking, often overlooked the intersecting oppressions faced by women of color and working-class women. It was, in essence, a project largely defined by and for white, bourgeois women. It demanded entry into a system that, arguably, needed dismantling, not merely integration.

B. The Second Wave: A Personal is Political. The second wave broadened the scope, highlighting issues like reproductive rights, sexuality, and domestic violence. The iconic rallying cry, “the personal is political,” underscored the understanding that seemingly private experiences are often shaped by larger power structures. Consciousness-raising groups became crucibles for feminist thought, forging solidarity and a shared understanding of patriarchal oppression.

C. Third Wave and Beyond: Intersectionality Ascendant. The third wave and subsequent iterations grappled with the limitations of previous waves, emphasizing intersectionality. This recognizes that gender oppression is inextricably linked to other forms of oppression, such as race, class, sexuality, and ability. One cannot fully understand the experiences of a Black woman, for instance, without considering the combined impact of racism and sexism. This wave critiques essentialism, the notion that all women share a universal experience. Instead, it celebrates the diversity and complexity of lived experiences.

II. Unpacking the Lexicon: Key Concepts in Feminist Critical Theory

A. Patriarchy: The Systemic Subjugation of Women. This isn’t about individual men being misogynistic (although that’s often part of it!). Patriarchy refers to a system of social structures and practices that privilege men and subordinate women. It operates at multiple levels: legal, economic, cultural, and interpersonal. It’s the invisible hand guiding resource allocation, shaping social norms, and perpetuating gender stereotypes.

B. Gender as a Social Construct: Beyond Biological Determinism. Gender is not simply determined by biology. It is a social construct, a set of norms and expectations about how individuals should behave based on their perceived sex. These norms are often rigid and oppressive, limiting individuals’ self-expression and reinforcing power imbalances. The performance of gender, as theorized by Judith Butler, is key to understanding how these norms are internalized and perpetuated. It’s a daily theatrical production, and we are all, to some extent, actors playing roles assigned to us.

C. Intersectionality: The Interlocking of Oppressions. As previously mentioned, this is crucial. It’s a corrective to universalizing narratives that fail to account for the diverse experiences of women. Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term, used the analogy of a traffic intersection: imagine different forms of oppression – racism, sexism, classism – as different lanes of traffic. Someone standing in the intersection is vulnerable to being hit by multiple streams of traffic simultaneously. This framework allows for a more nuanced understanding of power dynamics and challenges simplistic solutions.

D. Hegemonic Masculinity: The Dominant Ideal. This refers to the culturally idealized form of masculinity that legitimizes and maintains patriarchal dominance. It often involves characteristics like aggression, stoicism, and economic success. It’s not just about how men behave, but also about the standards against which they are judged. Men who deviate from this ideal are often marginalized or punished, reinforcing the power of hegemonic masculinity.

E. The Gaze: Objectification and Power. Laura Mulvey’s concept of the “male gaze” illuminates how women are often depicted in visual media as objects of male desire. This gaze is not neutral; it shapes how women are perceived and ultimately contributes to their objectification and subordination. It’s about who is looking and who is being looked at, and the power dynamics inherent in that act of looking.

III. Feminism in Action: Applying Critical Theory to Real-World Issues

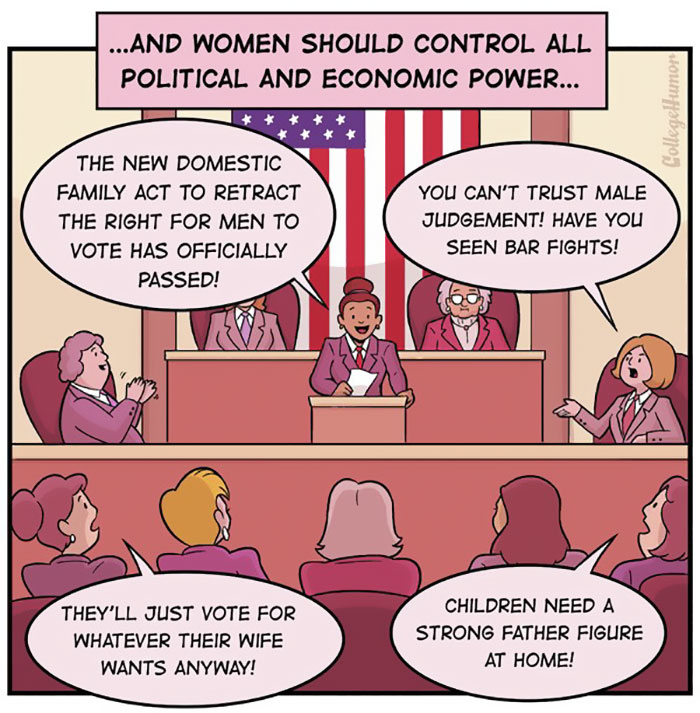

A. Media Representation: Deconstructing Stereotypes. Feminist critical theory provides tools to analyze media representations of women. Are women portrayed as passive objects, or as active agents? Are their stories diverse and complex, or are they reduced to simplistic stereotypes? Media analysis reveals how patriarchal norms are reinforced through the constant repetition of limiting narratives.

B. The Wage Gap: Beyond Simple Economics. The wage gap is not simply a matter of women being paid less for the same work. It reflects a deeper devaluation of women’s labor and skills. Feminist economists have demonstrated how the wage gap is linked to factors like occupational segregation, the undervaluing of care work (disproportionately performed by women), and the lack of adequate family leave policies. It’s about dismantling the systemic biases that perpetuate economic inequality.

C. Violence Against Women: A Spectrum of Coercion. Violence against women is not an isolated phenomenon; it is a manifestation of patriarchal power. It ranges from physical and sexual assault to emotional abuse and microaggressions. Feminist theorists have emphasized that violence against women is not just about individual acts; it is about a culture that normalizes and perpetuates male dominance.

D. Reproductive Rights: Bodily Autonomy as a Foundation. Access to safe and legal abortion is a fundamental human right. Feminist activists argue that reproductive rights are essential for women’s autonomy and equality. Restricting access to abortion disproportionately affects women of color and low-income women, exacerbating existing inequalities. It’s about control over one’s own body and the power to make informed decisions about one’s reproductive health.

E. Political Representation: Amplifying Marginalized Voices. Increasing women’s representation in political leadership is crucial, but it’s not enough. Feminist political theorists argue that it’s also necessary to challenge the patriarchal norms and structures that shape political discourse. It’s about creating a political landscape where diverse voices can be heard and where women can exercise genuine power.

IV. Challenges and Critiques: Navigating the Complexities of Feminist Thought

A. Essentialism vs. Anti-Essentialism: Reconciling Shared Experiences and Individual Differences. This is an ongoing debate. Can we speak of “women” as a unified group, or does that erase the diversity of experiences? Finding a balance between acknowledging shared experiences of gender oppression and recognizing individual differences is crucial.

B. The Problem of Male Allies: Navigating Power Dynamics. Can men be feminists? While male allyship is important, it’s crucial to be mindful of power dynamics. Allies should listen to and amplify the voices of women, rather than taking over the conversation. True allyship involves actively dismantling patriarchal structures and challenging misogynistic behavior.

C. Postfeminism: The Myth of Gender Equality. Postfeminism is the belief that feminism is no longer necessary because gender equality has already been achieved. This is a dangerous myth that ignores the persistent inequalities faced by women around the world. It’s a way of silencing feminist voices and dismissing the ongoing struggle for liberation.

D. Internalized Misogyny: Policing Ourselves and Each Other. This refers to the internalization of patriarchal beliefs and values by women. It can manifest as self-deprecating behavior, competition with other women, and the policing of other women’s choices. Recognizing and challenging internalized misogyny is crucial for dismantling patriarchal power within ourselves.

V. The Future of Feminist Critical Theory: Embracing Complexity and Intersectionality

A. Global Feminism: Addressing Transnational Inequalities. Feminism must be global in scope, addressing the specific challenges faced by women in different cultural contexts. This requires understanding the interplay of gender, colonialism, and globalization. It’s about solidarity and collaboration across borders.

B. Transgender Inclusion: Expanding the Definition of Gender. Transgender rights are feminist rights. Transgender women are women, and their experiences are essential to understanding the complexities of gender. Embracing transgender inclusion requires challenging rigid gender binaries and advocating for the rights of all individuals to self-determination.

C. Environmental Feminism (Ecofeminism): Connecting Gender and Environmental Justice. Ecofeminism argues that there is a connection between the oppression of women and the exploitation of the natural world. Both are seen as being devalued and dominated by patriarchal systems. Addressing environmental issues requires dismantling these systems and promoting a more sustainable and equitable future for all.

D. Technofeminism: Navigating the Digital Landscape. Technofeminism explores the intersection of gender and technology. It examines how technology can be used to empower women and challenge patriarchal norms, but also how it can perpetuate existing inequalities. It’s about creating a more equitable and inclusive digital world.

So, where does this leave us? Feminism, as a critical theory, is not a static dogma. It is a dynamic and evolving framework for analyzing power relations and challenging injustice. It demands constant self-reflection, a willingness to engage with diverse perspectives, and a commitment to dismantling all forms of oppression. It’s not just about tearing down the old; it’s about building a new world, one where everyone can thrive, free from the constraints of patriarchal norms.

Now, go forth and subvert!

Leave a Comment