Darling, let’s not mince words. We’re diving headfirst into the literary maelstrom that birthed modern feminism. Forget your vapid self-help guides and your influencer-endorsed affirmations. We’re talking about the bedrock, the sacred texts, the intellectual dynamite that shattered the patriarchal edifice. These books aren’t just “good reads;” they are blueprints for revolution. Why are we still drawn to them? Because the fight, sadly, rages on, and their wisdom remains tragically relevant. Because beneath the dust of ages, their radical hearts still beat.

So, grab your metaphorical battle axe, sharpen your wit, and let’s dissect these classics, shall we?

I. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) by Mary Wollstonecraft: The O.G. Disrupter

Ah, Wollstonecraft. The audacious broad who dared to suggest, in the late 18th century, that women weren’t just decorative ornaments but thinking, feeling beings capable of… gasp… rational thought! Her *Vindication* isn’t some polite request for equality; it’s a full-throated denunciation of societal structures that deliberately infantilize women.

Wollstonecraft’s central thesis revolves around education. She argues that women are rendered frivolous and dependent because they are denied access to proper education, a tool wielded deliberately to maintain patriarchal control. Is it a stretch to see echoes of this in contemporary debates about access to STEM fields for girls, or the persistent societal pressure on women to prioritize appearance over intellect? I think not.

Think about it. She boldly proclaimed that women should be educated, not for mere amusement or to become more appealing to men, but to become autonomous, virtuous citizens. The ramifications were, and still are, seismic. She advocates for a societal restructuring that values reason and virtue in all individuals, irrespective of gender. This isn’t just about women; it’s about the moral and intellectual health of society as a whole.

Her prose, while occasionally verbose by modern standards, pulsates with righteous indignation. She skewers the performative femininity of her time, exposing it as a tool of oppression. She challenges the very foundation of societal expectations. Consider the enduring power of that challenge. How often do we still see women judged by their adherence to antiquated notions of femininity? How often are their accomplishments minimized or dismissed based on their gender?

II. The Subjection of Women (1869) by John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill: A Liberal Lament

Moving forward almost a century, we encounter the intellectual powerhouse that was John Stuart Mill, aided significantly by his wife, Harriet Taylor Mill. *The Subjection of Women* is a meticulously argued, rational indictment of the legal and social subjugation of women. While less fiery than Wollstonecraft, its impact is no less profound.

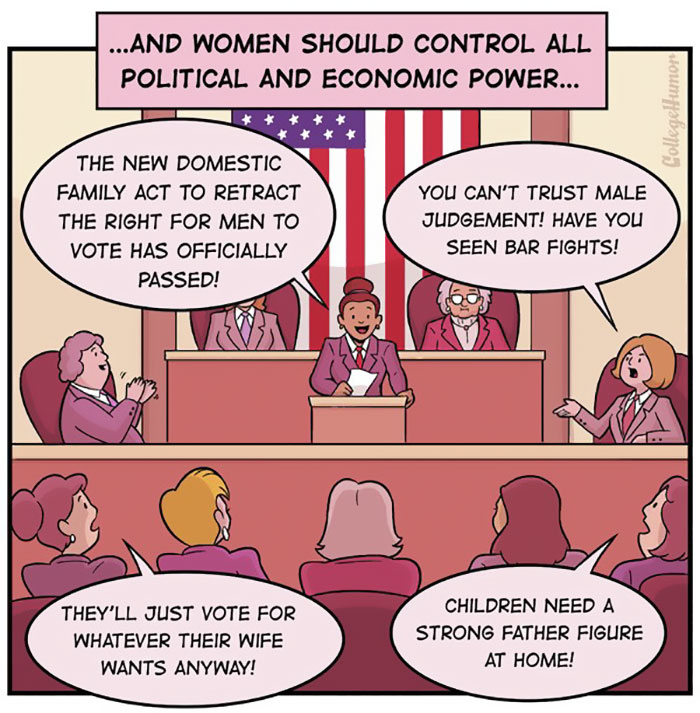

The Mills dissect the institution of marriage, exposing it as a legal contract that essentially enslaved women to their husbands. They argue that women’s lack of legal rights, their exclusion from education and employment, and their confinement to the domestic sphere constitute a grave injustice and a profound loss to society.

What truly sets this work apart is its unflinching commitment to logic and reason. They methodically dismantle the prevailing arguments for female inferiority, demonstrating that these arguments are based on prejudice and conjecture, not on empirical evidence. They highlight the insidious nature of societal conditioning, showing how women are taught from a young age to accept their subordinate status.

However, some critics have pointed to the Mills’s liberal individualism as a potential weakness. They emphasize individual rights and opportunities, which, while important, can sometimes overlook the systemic nature of oppression. Is true liberation possible within a system that remains inherently unequal? A question worth pondering.

III. A Room of One’s Own (1929) by Virginia Woolf: Literary Enfranchisement

Woolf, the queen of modernist prose, shifts the focus from legal and political rights to the more subtle but equally potent realm of artistic and intellectual freedom. In *A Room of One’s Own*, she famously argues that a woman needs “money and a room of her own” to write fiction. Simple, yet devastatingly true.

Her essay is not a polemic but a beautifully crafted exploration of the historical and social barriers that have prevented women from achieving literary greatness. She inventively creates the fictional character of Judith Shakespeare, William Shakespeare’s equally talented sister, to illustrate how societal constraints would have inevitably crushed her artistic aspirations.

Think about the subtle ways in which women are still denied the space, time, and resources to pursue their creative passions. Think about the disproportionate burden of domestic labor and childcare that often falls on women, limiting their opportunities for intellectual and artistic development. Woolf’s argument resonates just as powerfully today.

Woolf’s brilliance lies in her ability to connect the personal and the political. She shows how the seemingly mundane realities of daily life—lack of privacy, financial dependence, societal expectations—can have a profound impact on a woman’s ability to express herself creatively. It’s a reminder that liberation isn’t just about grand gestures and political pronouncements; it’s about the freedom to pursue one’s own passions, to create, to think, to be.

IV. The Second Sex (1949) by Simone de Beauvoir: Existential Excavations

Behold, de Beauvoir. *The Second Sex* is a monumental work of feminist philosophy that remains a cornerstone of feminist thought. De Beauvoir delves into the very essence of womanhood, arguing that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” This isn’t biology, darling; it’s a construction.

She meticulously examines the historical, mythological, and social forces that have shaped women’s identities, revealing how women have been consistently defined in relation to men, as “the Other.” This “Otherness” is the crux of her argument. Women are not seen as autonomous subjects but as objects, defined by their reproductive capacity, their roles as wives and mothers, and their perceived inferiority to men.

Consider the relentless pressure on women to conform to unrealistic beauty standards, to prioritize their appearance over their intellect, to define their worth in terms of their relationships with men. These are all manifestations of the “Otherness” that de Beauvoir so brilliantly dissects. It is a subjugation so insidious that it becomes internalized, shaping women’s self-perceptions and limiting their aspirations.

De Beauvoir encourages women to reject this imposed identity and to embrace their freedom and autonomy. She argues that women must actively create their own identities, define their own values, and pursue their own goals, independent of societal expectations. A call to arms, wrapped in philosophical prose.

V. The Feminine Mystique (1963) by Betty Friedan: Unveiling the Suburban Malaise

Friedan, armed with sociological insight, exposed “the problem that has no name”: the pervasive dissatisfaction and unhappiness of middle-class American housewives in the 1950s and early 1960s. *The Feminine Mystique* struck a nerve, sparking a wave of feminist consciousness across the nation.

Friedan argues that women were being systematically brainwashed into believing that their only fulfillment could be found in marriage, motherhood, and domesticity. She exposes the manipulative tactics of advertisers and the media, who relentlessly promoted this idealized image of the happy housewife, while simultaneously ignoring the intellectual and creative aspirations of women.

Think about the lasting impact of this “feminine mystique.” How many women still feel pressured to conform to traditional gender roles, to prioritize their families over their careers, to sacrifice their own ambitions for the sake of others? The problem may have evolved, but it hasn’t disappeared.

Friedan’s work is not without its limitations. Critics have pointed out that it primarily focuses on the experiences of white, middle-class women, neglecting the perspectives of women of color and working-class women. Nonetheless, its impact on the feminist movement cannot be denied. It gave voice to the unspoken discontent of a generation of women and helped to pave the way for a more inclusive and equitable society.

VI. Sisterhood Is Powerful (1970) edited by Robin Morgan: A Multifaceted Manifesto

Morgan’s edited collection is a kaleidoscopic blast of second-wave feminist thought. *Sisterhood Is Powerful* brought together essays, poems, and manifestos from a diverse range of feminist voices, addressing issues ranging from reproductive rights to workplace discrimination to violence against women. It’s a cacophony of rage, hope, and unwavering determination.

The book is a testament to the power of collective action. It shows how women from different backgrounds and with different experiences can come together to fight for a common cause. It challenges the notion that feminism is a monolithic movement and celebrates the diversity of feminist perspectives.

Consider the anthology’s groundbreaking discussions of sexuality, motherhood, and the intersection of gender with race, class, and sexual orientation. These were radical ideas at the time, and they continue to be relevant today.

VII. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981) by bell hooks: Intersectional Illumination

hooks, the sage of intersectionality, challenges the dominant narratives of feminism, arguing that they often neglect the experiences of Black women. *Ain’t I a Woman* is a searing critique of white feminism’s exclusionary practices and a powerful call for a more inclusive and intersectional feminist movement.

hooks argues that Black women face a unique form of oppression, rooted in the intersection of racism and sexism. She exposes the ways in which slavery and Jim Crow laws have historically marginalized Black women, denying them access to education, employment, and political power. She also critiques the ways in which mainstream feminist discourse often overlooks the specific challenges faced by Black women.

Think about the continued marginalization of Black women in politics, in the workplace, and in popular culture. Think about the persistent stereotypes that portray Black women as strong, independent, and resilient, while simultaneously denying them their vulnerability and humanity. hooks’s work is a reminder that feminism must be inclusive and intersectional if it is to truly liberate all women.

VIII. Gender Trouble (1990) by Judith Butler: Deconstructing the Binary

Butler, the academic provocateur, throws a grenade into the heart of gender essentialism. *Gender Trouble* is a dense, challenging, but ultimately groundbreaking work that deconstructs the very notion of gender as a fixed and stable identity. She argues that gender is not something we *are*, but something we *do*, a performance that is constantly reiterated and challenged through social interactions.

Butler challenges the binary opposition of male and female, arguing that gender is not a natural or biological given, but a social construct. She introduces the concept of “gender performativity,” which suggests that gender is not an internal essence but a set of behaviors and performances that are shaped by social norms and expectations.

Consider the implications of this theory for our understanding of gender identity. If gender is a performance, then it is fluid and malleable. It is not something that we are born with, but something that we actively create and negotiate throughout our lives. This opens up the possibility of challenging and subverting traditional gender roles and embracing a more diverse and inclusive understanding of gender identity.

These books are more than just historical artifacts; they are living documents that continue to inform and inspire the feminist movement. They remind us of the challenges that women have faced throughout history and the progress that has been made. But they also remind us of the work that still needs to be done. The fight for equality is far from over, and these classics provide us with the intellectual ammunition we need to continue the struggle.

Leave a Comment