Darling, ever pondered why we’re still dissecting the anatomy of inequality when history is littered with the bones of battles fought for equality? It’s because feminism, like a hydra, regenerates with ever more potent heads. The movement, a protean force, hasn’t been a monolithic entity; rather, a series of overlapping, sometimes conflicting, waves. Each cresting upon the shores of societal consciousness, leaving behind both flotsam and jetsam of progress. But also, tragically, new arenas for contestation.

Let us embark on a journey, shall we? To map this turbulent sea, delineating the contours of each wave, and understanding the undertow that threatens to pull us back into the abyssal depths of patriarchy. A journey not just through history, but through the very sinews of social change. Buckle up, buttercups; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

The Proto-Feminist Stirrings: A Whispered Rebellion (Pre-19th Century)

Before the organized clamor, there were whispers. A quiet rebellion brewing in the margins, penned by women deemed “eccentric” or “hysterical”. Proto-feminists, they were. These women dared to question the divinely ordained order of things, the presumed intellectual and moral inferiority of their sex. Figures like Christine de Pizan, in the 15th century, challenged misogynistic tropes with her pen, a dangerous weapon wielded with grace and intellect. Mary Wollstonecraft, writing during the Enlightenment, penned “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” (1792), a clarion call for education and rational liberty. A bold move for the era. Her words, a prescient articulation of feminist principles, reverberate even now. These were not merely isolated cries in the wilderness; they were the seeds of a future uprising, the embryonic stages of a movement yet to be born.

The challenge here is not simply acknowledging their existence, but grappling with the limited scope of their impact. How far did their revolutionary ideas travel beyond the gilded cages of the elite? Did they truly challenge the bedrock of patriarchal structures, or merely chip away at the edges?

First-Wave Feminism: Suffrage and Beyond (Late 19th – Early 20th Century)

The first wave crashed onto the shores of the 19th and early 20th centuries, fueled by a burning desire for enfranchisement. Suffrage, the right to vote, was the lodestar guiding their actions. Women, deemed too emotional, too irrational, too delicate for the political sphere, were rising up to demand their rightful place at the table. Figures like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, titans of the movement, tirelessly campaigned, organized, and endured ridicule and imprisonment. Their arguments, steeped in the language of natural rights and republicanism, resonated with a growing segment of society. It was not simply about casting a ballot; it was about asserting their citizenship, their personhood, their inherent equality.

However, let’s not romanticize this era. The first wave, while transformative, was not without its blind spots. Its focus often remained firmly rooted in the experiences of white, middle-class women. The voices and concerns of women of color, working-class women, and women from marginalized communities were frequently sidelined or outright ignored. The fight for suffrage, while undeniably crucial, became a singular objective that sometimes eclipsed other pressing issues, like economic justice and reproductive rights. So, the question lingers: how do we reconcile the undeniable achievements of the first wave with its inherent limitations and exclusions?

Second-Wave Feminism: Liberation and Radicalism (1960s-1980s)

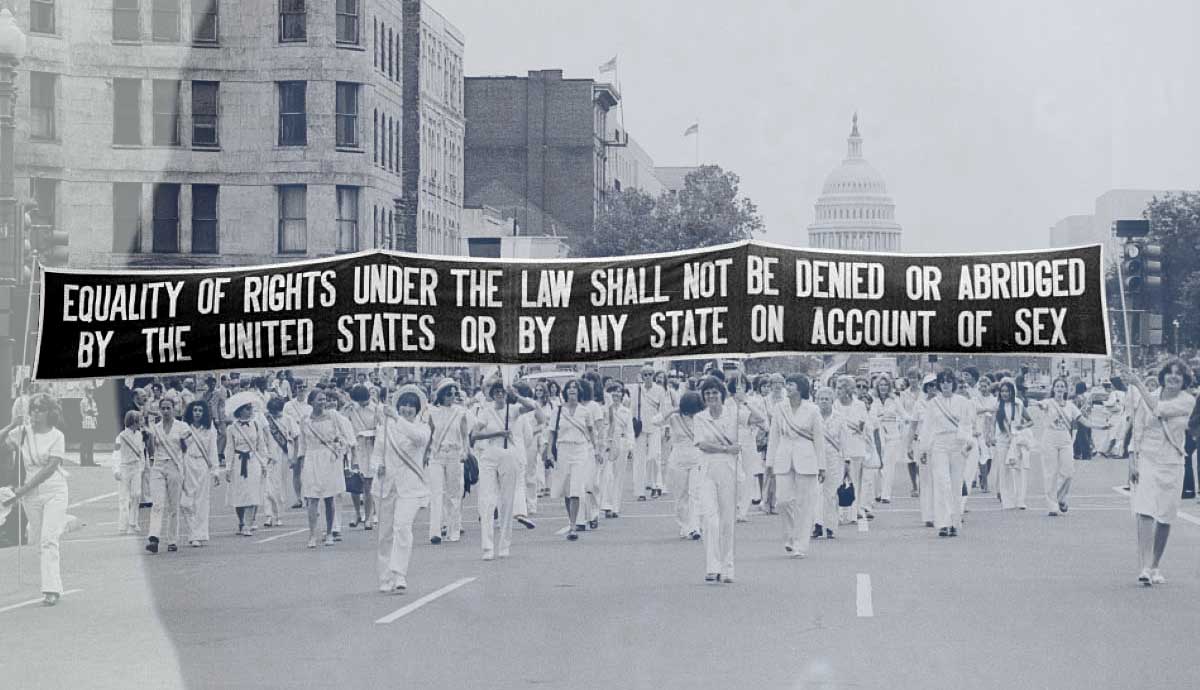

The second wave, emerging from the social and political ferment of the 1960s, expanded the feminist agenda exponentially. Fueled by the burgeoning Civil Rights movement and anti-war protests, second-wave feminists challenged not just legal inequalities, but also deeply ingrained cultural norms and societal expectations. “The personal is political” became the mantra of the movement, highlighting the ways in which seemingly private issues, like domestic violence, reproductive health, and sexual harassment, were in fact manifestations of systemic oppression. Works like Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” (1963) exposed the suffocating confines of suburban domesticity, while radical feminists like Shulamith Firestone called for a complete dismantling of patriarchal structures.

This wave witnessed the rise of consciousness-raising groups, women coming together to share their experiences, analyze the root causes of their oppression, and collectively strategize for change. They demanded equal pay, access to abortion, and an end to all forms of discrimination. The second wave was a kaleidoscope of diverse voices and perspectives, from liberal feminists advocating for legislative reform to socialist feminists critiquing the capitalist underpinnings of patriarchy. However, internal divisions and competing priorities threatened to fracture the movement.

A critical challenge arises: did the second wave truly transcend the limitations of its predecessors, or did it simply replicate them in new and insidious ways? The persistent critique that second-wave feminism was predominantly white and middle-class, failing to adequately address the experiences of women of color and working-class women, remains a potent and uncomfortable truth. Furthermore, the debate over sexuality and gender roles often proved divisive, leading to clashes between radical feminists and lesbian activists.

Third-Wave Feminism: Intersectionality and Individualism (1990s-2010s)

The third wave, a reaction to the perceived shortcomings of its predecessor, emerged in the 1990s, characterized by a heightened awareness of intersectionality. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality, highlighting the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, became a cornerstone of third-wave feminist thought. Rejecting essentialist notions of womanhood, third-wave feminists embraced diversity and celebrated individual expression. They challenged traditional gender roles, reclaimed derogatory terms like “slut” and “bitch”, and embraced a more fluid and nuanced understanding of identity.

The internet and social media became powerful tools for third-wave feminists to connect, organize, and disseminate their ideas. Online blogs, zines, and social media campaigns amplified the voices of marginalized women and provided platforms for challenging misogyny and sexism in popular culture. However, the emphasis on individualism and self-expression also drew criticism. Some argued that third-wave feminism had become too focused on personal empowerment, neglecting the structural inequalities that continued to oppress women.

The central challenge here revolves around the tension between individual agency and collective action. Did the third wave, in its celebration of individual expression, lose sight of the need for systemic change? Did the focus on micro-aggressions and everyday sexism overshadow the more profound forms of oppression that disproportionately affect women of color, working-class women, and women from marginalized communities?

Fourth-Wave Feminism: Digital Activism and Global Solidarity (2010s-Present)

The fourth wave, fueled by the power of the internet and social media, is characterized by a renewed focus on issues such as sexual harassment, rape culture, body positivity, and transgender rights. The #MeToo movement, a watershed moment in the fight against sexual assault and harassment, demonstrated the power of collective action in the digital age. Fourth-wave feminists are using social media platforms to expose perpetrators of abuse, share their stories, and demand accountability. This wave also emphasizes global solidarity, recognizing that the struggle for gender equality is a global one, with women around the world facing unique challenges and forms of oppression.

Online activism, however, is not without its perils. The echo chambers of social media can reinforce existing biases and create new forms of division. Cyberbullying, online harassment, and the spread of misinformation pose significant threats to the movement. Furthermore, the accessibility of online activism can sometimes lead to performative allyship, where individuals engage in symbolic gestures of support without making meaningful contributions to the cause.

A crucial challenge for the fourth wave lies in translating online activism into tangible social change. How can we harness the power of the internet to build lasting coalitions, enact meaningful legislation, and dismantle the systemic structures that perpetuate gender inequality? How do we ensure that online activism does not become a substitute for real-world engagement, but rather a catalyst for it?

The Unfolding Future: Intersectional Praxis and the Enduring Struggle

So, where do we stand now? The tides of feminism continue to ebb and flow, shaped by the ever-changing social and political landscape. We are at a critical juncture, facing a resurgent backlash against feminist gains and a proliferation of new forms of misogyny and inequality. The challenges are formidable, but so is our resolve. The future of feminism lies in embracing intersectional praxis, acknowledging the interconnected nature of oppression, and building inclusive movements that prioritize the voices and experiences of the most marginalized. It requires a commitment to critical self-reflection, a willingness to challenge our own biases and assumptions, and a deep understanding of the historical context in which we operate. It is a call to action, a demand for justice, and a promise of a more equitable and just world for all. The task ahead is monumental, requiring an intricate dance between radical vision and pragmatic strategy. Are we up to the challenge, darlings? The future is feminist, or it is nothing at all.

Leave a Comment