Feminism, a protean and perpetually evolving socio-political crucible, has long been intimately intertwined with the rigorous and often unsettling realm of philosophy. Why this enduring dance? Why this relentless interrogation of power, knowledge, and being through the lens of gender? It’s not simply about achieving parity in the workplace or equal representation in government. It’s about excavating the very foundations of Western thought, exposing the fault lines beneath patriarchal structures, and building anew, a world where flourishing isn’t predicated on subjugation. It’s a project of epistemological and ontological recalibration.

This article delves into the seminal ideas that have fueled this transformative movement, charting a course through the philosophical terrain where feminism has not only challenged established norms but fundamentally reshaped our understanding of power itself. From Simone de Beauvoir’s existentialist rebellion to Judith Butler’s deconstruction of gender, we will explore the key theoretical interventions that have redefined what it means to be, to know, and to resist.

The Existentialist Uprising: Beauvoir’s Challenge to Immanence

Before the second wave crested, Simone de Beauvoir, a philosopher of profound insight, penned *The Second Sex*, a text that arguably ignited the modern feminist project. Beauvoir, steeped in the existentialist tradition of Sartre and Heidegger, argued that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” This wasn’t a mere biological observation; it was a philosophical declaration of independence. Society, she argued, conspires to confine women to a state of “immanence,” a passive existence defined by their relationship to men.

Contrast this with the masculine prerogative of “transcendence,” the active, self-defining pursuit of projects and goals. Patriarchy, in Beauvoir’s analysis, systematically denies women the opportunity to transcend, trapping them in roles of wife, mother, and muse, thereby hindering their full realization as autonomous beings. This concept is not merely sociological; it’s deeply philosophical, challenging the very essence of what it means to be human. Beauvoir’s work laid the groundwork for a feminism that demanded not just equality but the freedom to define oneself, to forge one’s own essence through lived experience.

Deconstructing the Phallus: Psychoanalysis and the Feminist Critique

Psychoanalysis, with its focus on the unconscious and the dynamics of desire, initially seemed an unlikely ally to feminism. Freud’s theories, particularly his concept of “penis envy,” were often interpreted as reinforcing patriarchal norms. However, feminist thinkers, notably those influenced by Jacques Lacan, embarked on a critical deconstruction of psychoanalytic theory, turning its own tools against it.

Thinkers like Luce Irigaray questioned the very notion of the phallus as the singular signifier of power and desire. Irigaray argued that Western thought is fundamentally phallocentric, privileging the masculine perspective and marginalizing the feminine. She advocated for a re-evaluation of female sexuality, moving beyond the phallus as the sole source of erotic pleasure and exploring the multiplicity of female desire. This involves not just a critique of Freud, but a radical reimagining of the symbolic order itself.

Julia Kristeva, another influential figure, introduced the concept of the “semiotic,” a pre-linguistic realm of drives and affects that exists outside the symbolic order. She argued that the semiotic, often associated with the maternal, offers a source of disruption and creativity that can challenge the rigid structures of patriarchal language and thought. This critique pushes beyond simple equality; it seeks to destabilize the very foundations upon which patriarchal power rests.

The Personal is Political: Radical Feminism and the Micropolitics of Power

The second wave of feminism witnessed the rise of radical feminism, a movement that sought to dismantle patriarchy at its roots. Radical feminists challenged the traditional separation between the personal and the political, arguing that seemingly private experiences, such as domestic violence and reproductive rights, are in fact deeply political issues.

Key figures like Carol Hanisch articulated the now-famous phrase, “the personal is political,” highlighting the ways in which power operates not just in the public sphere but also in the intimate relationships of everyday life. This insight led to the development of consciousness-raising groups, where women shared their experiences and collectively analyzed the systemic nature of their oppression. This wasn’t just about airing grievances; it was about building a collective understanding of how power structures operate at the micro-level, shaping individual identities and experiences.

Radical feminists also challenged traditional notions of sexuality, arguing that heterosexuality is a social construct designed to maintain male dominance. Some advocated for lesbian separatism, a radical rejection of heterosexual relationships as inherently oppressive. This emphasis on sexuality as a site of political struggle was a crucial contribution to feminist theory, paving the way for later discussions of intersectionality and queer theory.

Epistemological Disobedience: Challenging the Gaze and Reclaiming Knowledge

Feminist epistemology challenges the assumption that knowledge is objective and value-neutral. Thinkers like Sandra Harding argued that knowledge is always situated, shaped by the social and political context in which it is produced. This insight has profound implications for how we understand science, history, and other fields of knowledge.

Harding introduced the concept of “standpoint theory,” which argues that marginalized groups, such as women and people of color, have a unique perspective on the world because of their experiences of oppression. This perspective can provide valuable insights that are often overlooked by those in positions of power. It’s not about claiming moral superiority, but about recognizing the epistemic privilege that comes from being positioned outside the dominant narrative.

Other feminist epistemologists, like Donna Haraway, have challenged the notion of objectivity altogether, arguing that all knowledge is partial and situated. Haraway’s concept of “situated knowledges” emphasizes the importance of acknowledging the limitations of our own perspectives and engaging with other viewpoints in a spirit of humility and openness. This represents a fundamental challenge to the traditional Western pursuit of universal and objective truth. A pursuit which often masks entrenched power dynamics.

Gender as Performance: Butler’s Deconstruction of Identity

Judith Butler’s *Gender Trouble* is a landmark text in queer theory and feminist thought. Butler challenged the very idea of gender as a fixed and stable category, arguing that it is instead a performance, a repeated set of acts that create the illusion of an underlying essence. This concept of “performativity” is crucial to understanding how gender norms are constructed and maintained.

Butler argued that gender is not something we *are*, but something we *do*. By repeatedly performing certain acts, we reinforce the idea that there are only two genders, male and female. However, because gender is performative, it is also open to subversion. By disrupting gender norms through drag, cross-dressing, or other forms of gender transgression, we can expose the artificiality of gender and create space for new possibilities of identity.

Butler’s work has been both lauded and criticized. Some argue that it undermines the political project of feminism by deconstructing the very category of “woman.” Others argue that it provides a powerful tool for challenging gender norms and creating a more inclusive and just society. It is a complex and challenging argument, but one that has profoundly shaped contemporary feminist thought. It forces us to confront the very nature of identity and the ways in which it is shaped by power.

Intersectionality: Recognizing the Complexities of Oppression

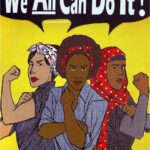

The concept of intersectionality, developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, recognizes that individuals can experience multiple forms of oppression simultaneously. A Black woman, for example, may face both racism and sexism, which interact in complex ways to shape her experiences. This insight is crucial for understanding the limitations of a feminism that focuses solely on gender, without considering the impact of race, class, sexuality, and other forms of social inequality.

Intersectionality challenges us to move beyond single-axis frameworks of analysis and to recognize the interconnectedness of different forms of oppression. It requires us to listen to the voices of marginalized groups and to understand how their experiences are shaped by the intersection of multiple identities. It’s a call for a more nuanced and inclusive feminism, one that recognizes the complexities of human experience.

The Future of Feminist Philosophy: Towards a More Just and Equitable World

Feminist philosophy continues to evolve, grappling with new challenges and expanding its horizons. Contemporary feminist thinkers are engaging with issues such as transgender rights, environmental justice, and the impact of technology on gender relations. They are also exploring new methodologies, such as affect theory and posthumanism, to better understand the complexities of power and identity.

The ongoing project of feminist philosophy is not just about critiquing existing power structures; it is also about envisioning and creating a more just and equitable world. It’s about building a world where all individuals have the opportunity to flourish, regardless of their gender, race, or other social identities. It’s a challenging and complex task, but one that is essential for the future of humanity.

The dance between philosophy and feminism is far from over. It is a vital and ongoing conversation, one that continues to challenge our assumptions, disrupt our complacency, and push us towards a more just and equitable future. The very act of questioning, of relentlessly interrogating the foundations of power, remains the most potent tool in the feminist arsenal. And it is a tool that must be wielded with both precision and passion if we are to truly reshape the world.

Leave a Comment