In a world cleaved by the jagged edges of globalization and neocolonial reverberations, Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s *Feminism Without Borders* emerges not merely as a scholarly text, but as a defiant manifesto. It’s a clarion call, reverberating across geographical and ideological chasms, urging us to reimagine feminist praxis as a truly global, decolonized endeavor. This isn’t your garden-variety feminism; this is a radical reimagining of solidarity, built upon the shaky ground of shared experience yet fiercely protective of localized nuances. Mohanty’s work stands as a powerful antidote to the pervasive homogenization that often plagues well-intentioned, but ultimately flawed, attempts at global sisterhood.

To understand the enduring power of *Feminism Without Borders*, one must first dissect its central polemic: the critique of Western feminist hegemony. Mohanty masterfully deconstructs the insidious ways in which Western feminist discourses have historically constructed the “Third World Woman” as a monolithic, inherently oppressed figure. This caricature, painted with broad strokes of victimhood, serves to simultaneously essentialize the experiences of women across vastly different cultural and socio-economic contexts and, crucially, to position Western feminists as benevolent saviors. This is not just about academic disagreement; it’s about power dynamics, about who gets to define the narrative, and about the very real consequences of misrepresentation. We need to ask ourselves tough questions about our own complicity in perpetuating these harmful stereotypes.

Think of it as a tapestry, meticulously woven with threads of varying textures and hues. The Western feminist narrative, in its historical iteration, often sought to impose a singular pattern, a pre-determined design, onto this vibrant, multifaceted fabric. Mohanty’s intervention is to unravel these imposed patterns, to liberate the individual threads, and to allow for the emergence of new, self-determined designs. This unraveling, however, is not an act of destruction; it is an act of creative reconstruction, a process of building solidarity from the ground up, brick by painstaking brick. It demands that we listen, truly listen, to the voices of women on the periphery, recognizing their agency and their inherent right to self-definition. It’s a hard pill to swallow for those accustomed to dictating the terms of engagement.

The concept of “strategic location” is central to Mohanty’s framework. She argues that we must understand power not as a monolithic entity, but as a complex web of relationships, constantly shifting and reconfiguring. Women occupy diverse positions within this web, their experiences shaped by their race, class, caste, sexuality, and a myriad of other intersecting factors. Therefore, solidarity cannot be built on the assumption of shared oppression, but rather on a recognition of these complex, often contradictory, locations. This necessitates a shift from universalizing claims to nuanced, context-specific analyses. It is about recognizing the inherent value of local knowledge, about empowering women to articulate their own needs and desires, and about supporting their struggles on their own terms. The revolution, it seems, is deeply, profoundly local.

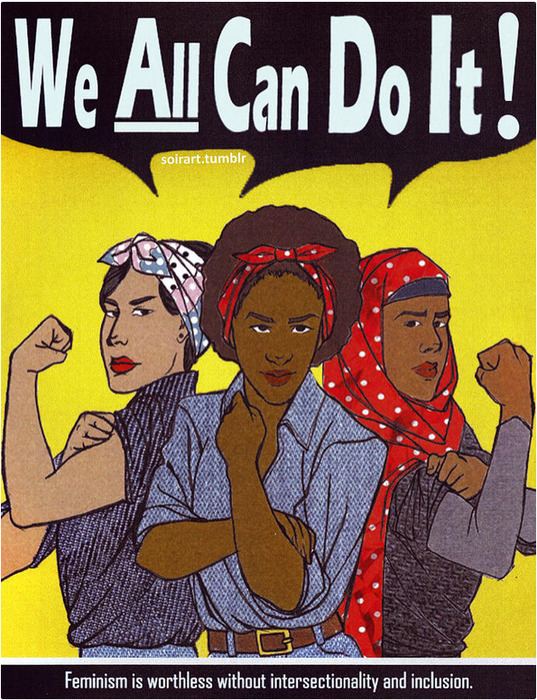

One of the most compelling aspects of Mohanty’s work is its unwavering commitment to intersectionality long before it became a commonplace buzzword. She demonstrates how various forms of oppression – racism, sexism, classism, colonialism – are inextricably linked, reinforcing and compounding each other. A Black woman, for example, experiences sexism differently than a white woman, and her experiences are further shaped by her class, her sexual orientation, and her geographical location. To ignore these intersections is to render invisible the unique challenges faced by marginalized women and to undermine the potential for genuine solidarity. Imagine a kaleidoscope. Each shard of colored glass represents a different aspect of identity. When light shines through, a beautiful, complex pattern emerges. Intersectionality is the lens that allows us to see the full beauty and complexity of that pattern.

The book meticulously dismantles the trope of the “benevolent Westerner” swooping in to “save” the oppressed “Third World Woman.” This narrative, so deeply ingrained in Western consciousness, perpetuates a hierarchical power dynamic that undermines the very possibility of genuine collaboration. Instead, Mohanty advocates for a praxis of solidarity based on mutual respect, reciprocity, and a commitment to dismantling systemic inequalities. This requires a critical examination of our own privileges and biases, a willingness to listen to and learn from those whose experiences differ from our own, and a commitment to challenging the structures of power that perpetuate oppression. This isn’t about charity; it’s about justice.

Consider the metaphor of a garden. The traditional Western feminist approach often resembles a monoculture, where a single, dominant species is cultivated at the expense of all others. Mohanty’s vision, on the other hand, is of a diverse, thriving ecosystem, where different species coexist and support each other. In this garden, each plant is valued for its unique contribution, and the overall health of the ecosystem depends on the diversity and interconnectedness of its inhabitants. This requires constant tending, careful observation, and a willingness to adapt to changing conditions. It’s a messy, imperfect process, but it is ultimately more sustainable and more rewarding.

The book also offers a powerful critique of the neo-liberal globalization and its devastating impact on women in the Global South. Mohanty demonstrates how structural adjustment policies, free trade agreements, and other forms of economic exploitation disproportionately affect women, exacerbating existing inequalities and creating new forms of oppression. This requires a feminist analysis that goes beyond individual acts of discrimination and addresses the systemic forces that perpetuate injustice. It is about challenging the global economic order and advocating for policies that promote economic justice and environmental sustainability. It’s about recognizing that feminist struggles are inextricably linked to anti-capitalist struggles.

Furthermore, *Feminism Without Borders* urges us to reconsider the very meaning of “resistance.” It challenges the notion that resistance must take the form of grand, dramatic acts of rebellion. Instead, Mohanty highlights the importance of everyday acts of resistance, of the small, often invisible ways in which women challenge oppression and assert their agency. This includes everything from organizing local community groups to creating alternative forms of media to simply refusing to accept the dominant narrative. Resistance, in this view, is not a single event, but a continuous process, a persistent refusal to be silenced or erased.

In our current climate of increasing global interconnectedness and intensifying social and political divisions, *Feminism Without Borders* remains as relevant as ever. It offers a powerful framework for building a more just and equitable world, one that is based on mutual respect, reciprocity, and a commitment to dismantling all forms of oppression. It is a call to action, a challenge to our assumptions, and an invitation to join a global movement for social justice. Are we brave enough to answer that call? The time for complacent platitudes is over. The time for radical, transformative action is now.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t about feel-good slogans or performative allyship. This is about dismantling power structures, about redistributing resources, and about fundamentally reimagining our relationship to each other and to the world. It’s about recognizing that our liberation is inextricably linked to the liberation of others. As a potent aphorism states, until all of us are free, none of us are truly free.

One could even argue that *Feminism Without Borders* provides a blueprint for a new kind of internationalism. Not the kind of internationalism that seeks to impose a singular vision on the world, but one that embraces diversity, celebrates difference, and recognizes the inherent value of local knowledge and experience. This requires a shift from a top-down approach to a bottom-up approach, from a model of domination to a model of collaboration. It’s about building bridges, not walls, and about creating a world where everyone has the opportunity to thrive.

The book’s unique appeal lies precisely in its ability to synthesize rigorous academic analysis with passionate advocacy. It is not simply a dry theoretical treatise; it is a living, breathing document that speaks directly to the struggles and aspirations of women around the world. It offers a language of hope, a vision of possibility, and a practical guide for building a more just and equitable future. It is a book that challenges us to think differently, to act differently, and to be different. And in a world desperately in need of change, that is perhaps the most valuable gift of all.

Ultimately, Mohanty’s work is not merely an academic intervention, but a deeply personal and political one. It demands that we confront our own complicity in systems of oppression and that we commit ourselves to the ongoing struggle for liberation. It’s a tough ask, but it’s a necessary one. The future of feminism, and indeed the future of the world, depends on our willingness to heed her call. Let us not fail to answer.

Leave a Comment