Does the very act of claiming a ‘woman’ identity solidify the patriarchal structures we desperately seek to dismantle? A tantalizing, perhaps terrifying, proposition. Judith Butler, with her seismic work *Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity*, didn’t just stir the pot of feminist discourse; she detonated a philosophical grenade within it. The reverberations continue to shape and reshape our understanding of gender, power, and the very foundations of identity itself.

The feminist project, traditionally anchored in the assertion of a unified female experience, found itself facing an uncomfortable mirror. Butler held it up, reflecting back the inherent dangers of essentialism, of assuming a singular, universal “woman” around which to rally. Such an assumption, she argued, risks replicating the exclusionary practices it seeks to overthrow, marginalizing those who don’t fit neatly into the pre-defined mold. The implications? Profound, necessitating a re-evaluation of feminist strategies and goals.

I. Deconstructing the Category of ‘Woman’: A Foundational Challenge

Butler’s deconstruction of “woman” isn’t about denying the reality of female experience. It’s about interrogating the very construction of that category. She challenges the notion of a pre-existing, stable identity onto which social and cultural meanings are simply grafted. Instead, she posits that “woman,” like all identities, is a product of discourse, of power relations, constantly being (re)made through language and social practices.

A. The Problem of Essentialism: To claim that all women share a common essence, a set of innate characteristics, is to fall prey to essentialism. This, according to Butler, inevitably leads to exclusion. Women of color, queer women, disabled women – all are potentially rendered invisible by a feminism that prioritizes a narrow, often white, middle-class ideal. Short-sighted indeed.

B. Beyond Biological Determinism: Butler rejects the idea that biology is destiny. Sex, she argues, is not simply a given but is itself discursively constructed. The way we understand and categorize bodies is shaped by cultural norms and power dynamics, not by some objective biological reality. A provocative claim, to be sure, but one with far-reaching consequences.

C. The Role of Discourse: Language doesn’t merely describe reality; it actively shapes it. The way we talk about gender, the categories we use, the stories we tell – all contribute to the construction of gendered identities. Butler draws heavily on post-structuralist thought, particularly the work of Michel Foucault, to demonstrate how power operates through discourse, producing and regulating subjects.

II. Gender as Performance: Beyond the Binary

Perhaps the most controversial and widely misunderstood aspect of Butler’s work is her concept of gender as performance. It is crucial to underscore that ‘performance’ is not synonymous with theatricality or conscious choice. Rather, it refers to the repeated, stylized acts through which we enact and embody gendered norms.

A. The Iterative Nature of Gender: Gender is not a fixed attribute but an ongoing process. We “do” gender through our everyday actions, our clothing, our speech, our interactions with others. These acts, repeated over time, solidify into what we perceive as a coherent gender identity. It is through this reiteration that the illusion of a stable self is created.

B. Subversion and Agency: While gender is imposed upon us by social norms, Butler insists that there is always room for agency. By consciously disrupting and subverting these norms, we can challenge the very foundations of the gender binary. Drag, for example, can be seen as a form of gender parody, exposing the constructed nature of gender itself.

C. Beyond Mimicry: The concept of performance does not suggest that gender is simply a matter of mimicking pre-existing roles. It’s more complex than that. We are all, in a sense, performing gender, even when we believe we are being “authentic.” The very notion of authenticity is itself a product of the system we are trying to escape.

III. The Matrix of Gender, Sex, and Sexuality: Untangling the Knots

Butler argues that gender, sex, and sexuality are intertwined in a complex and often contradictory manner. The traditional view posits a linear relationship: sex determines gender, and gender determines sexuality. Butler disrupts this model, demonstrating that each category is socially constructed and mutually constitutive.

A. Challenging the Sex/Gender Distinction: The distinction between sex (biological) and gender (social) has been a cornerstone of feminist thought. Butler argues that this distinction, while seemingly helpful, ultimately reinforces the idea that there is a natural, pre-cultural basis for gender. Instead, she proposes that sex itself is already gendered, shaped by cultural norms and power relations.

B. Heteronormativity and its Discontents: Heteronormativity, the assumption that heterosexuality is the natural and inevitable form of sexuality, is a key target of Butler’s critique. She argues that heteronormativity is not just a set of beliefs but a powerful system of regulation that shapes our understanding of gender and sexuality, marginalizing those who deviate from the norm. Its insidious tendrils reach everywhere.

C. The Performative Production of Sex: Just as gender is performatively produced, so too is sex. The medical establishment, for example, plays a crucial role in defining and categorizing bodies, reinforcing the binary distinction between male and female. These categories, however, are not objective but are shaped by cultural and historical forces.

IV. Implications for Feminist Politics: Towards a More Inclusive Future

Butler’s work has had a profound impact on feminist politics, challenging traditional assumptions and opening up new avenues for activism and resistance. Her emphasis on deconstruction, performance, and the interconnectedness of gender, sex, and sexuality has forced feminists to confront the complexities of identity and power.

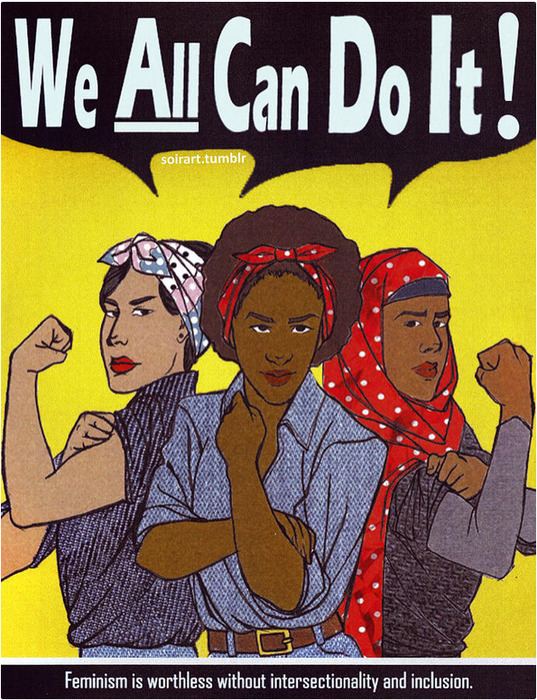

A. Embracing Difference and Contingency: A Butlerian feminism embraces difference rather than seeking a unified female experience. It acknowledges that there is no single “woman” but rather a multitude of experiences shaped by race, class, sexuality, disability, and other factors. This requires a commitment to intersectionality and a willingness to challenge one’s own assumptions.

B. Challenging Normative Frameworks: Butler’s work encourages us to challenge all normative frameworks, including those that define what it means to be a “good” woman or a “real” man. By disrupting these norms, we can create space for more diverse and fluid expressions of gender and sexuality. A liberating prospect, indeed.

C. Beyond Identity Politics: While identity is important, Butler cautions against relying too heavily on identity politics. The focus should be on challenging the power structures that shape and constrain identity, rather than simply asserting a particular identity. This requires a shift from recognition to redistribution, from identity to justice.

D. The Power of Parody and Subversion: Butler sees parody and subversion as powerful tools for challenging gender norms. By exaggerating and mocking these norms, we can expose their artificiality and undermine their authority. Drag, as mentioned earlier, is a prime example of this form of resistance.

V. Criticisms and Ongoing Debates: Navigating the Complexities

Butler’s work has not been without its critics. Some accuse her of being overly abstract and inaccessible, of losing sight of the lived realities of women’s oppression. Others argue that her emphasis on performance undermines the seriousness of gender inequality.

A. The Charge of Abstraction: Some critics argue that Butler’s dense and theoretical prose makes her work inaccessible to a wider audience. They contend that her focus on deconstruction and performance distracts from the more pressing issues of economic inequality and violence against women. Is this critique valid? Perhaps, but simplification risks losing nuance.

B. The Risk of Relativism: By deconstructing the category of “woman,” some fear that Butler undermines the basis for feminist solidarity. If there is no essential “woman,” how can we unite to fight for women’s rights? This is a legitimate concern, but Butler argues that solidarity can be built on shared experiences of oppression rather than on a shared identity.

C. The Problem of Agency: Critics also question whether Butler’s emphasis on performance leaves enough room for individual agency. If gender is simply a matter of repeating social norms, how can we ever hope to break free from them? Butler responds that agency is always possible, even within a system of constraint. The struggle is inherent.

VI. Conclusion: A Legacy of Disruption and Transformation

Judith Butler’s *Gender Trouble* remains a seminal work in feminist theory, challenging us to rethink our assumptions about gender, power, and identity. While her work is complex and often controversial, its impact on feminist politics and queer theory is undeniable. It has forced us to confront the limitations of essentialism, to embrace difference, and to challenge the normative frameworks that shape our lives. The legacy? A more nuanced, inclusive, and ultimately more powerful feminism, one that continues to evolve and adapt in the face of ongoing social and political change. It is a call not to comfort but to constant critical engagement. The subversion continues.

Leave a Comment