The question hangs in the air, a miasma of doubt and recrimination: Has feminism, in its relentless pursuit of equity, overstepped its bounds? Has the pendulum swung too far, leaving wreckage in its wake? The accusation, often levied with a sneer, is that feminism has morphed into an extremist ideology, a bludgeon wielded against men, a force fracturing the very social fabric it purports to mend. Is there truth to this accusation? Or is it merely a convenient canard, a shield brandished by those unwilling to confront the persistent asymmetries of power that continue to define our world?

Let’s not mince words. The backlash is real. It simmers in the undercurrents of online discourse, erupts in the pronouncements of self-proclaimed anti-feminists, and subtly permeates mainstream narratives. It’s a whisper campaign, amplified by algorithms, that paints feminism as a monolithic entity, a hydra-headed monster devouring all that is sacred and traditional. And, like any effective propaganda, it contains grains of truth, twisted and distorted to serve a specific agenda.

One of the most frequent charges is that feminism has become synonymous with misandry – a hatred of men. It’s a potent accusation, designed to delegitimize the entire movement by painting it as inherently biased. Are there feminists who harbor animosity towards men? Undoubtedly. Are they representative of the vast and diverse landscape of feminist thought? Absolutely not. To equate feminism with misandry is to commit a fallacy of composition, conflating the actions of a few with the beliefs of the many. It’s a cheap rhetorical trick, designed to silence dissent and delegitimize legitimate grievances.

Another common critique centers on the concept of “toxic masculinity.” This term, intended to describe harmful societal expectations placed upon men, is often misconstrued as an attack on masculinity itself. The argument goes that feminism is attempting to emasculate men, to strip them of their inherent qualities and force them into a gender-neutral mold. This is, quite frankly, a gross misrepresentation. The goal isn’t to eradicate masculinity, but to redefine it, to liberate men from the suffocating constraints of traditional gender roles that often lead to violence, emotional repression, and a host of other societal ills. The true enemy isn’t masculinity, but the rigid, performative machismo that demands conformity and punishes vulnerability.

Consider, for instance, the expectation that men must always be strong and stoic, impervious to pain or emotion. This demand, internalized from a young age, can have devastating consequences, leading to higher rates of suicide, substance abuse, and chronic stress. Feminism, at its core, seeks to dismantle these harmful expectations, to create a society where men are free to express their emotions, pursue their passions, and forge their own identities without fear of judgment or reprisal. Is this emasculation? Or is it liberation?

The debate surrounding the #MeToo movement provides another fertile ground for anti-feminist sentiment. While the movement undeniably brought to light the pervasive nature of sexual harassment and assault, critics argue that it has gone too far, creating a climate of fear and suspicion where innocent men are unfairly targeted. They decry the erosion of due process, the rush to judgment, and the potential for false accusations to ruin lives. There is merit to some of these concerns. The justice system, even in the best of circumstances, is imperfect, and the potential for error always exists. However, to focus solely on the potential for false accusations is to ignore the systemic silencing of victims that has allowed sexual violence to flourish for centuries. The #MeToo movement was a necessary reckoning, a collective scream against a culture of impunity. To dismiss it as mere hysteria is to minimize the suffering of countless individuals who have been silenced and marginalized for far too long.

Moreover, the argument that innocent men are being unfairly targeted often ignores the power dynamics at play. Sexual harassment and assault are rarely random acts of violence; they are often perpetrated by individuals in positions of power who exploit their authority to take advantage of those who are vulnerable. The #MeToo movement sought to level the playing field, to empower victims to speak out against their abusers without fear of retaliation. Is this an overreach? Or is it a necessary correction to a system that has historically favored the powerful and privileged?

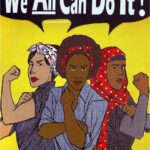

Another common refrain is that feminism has become too focused on identity politics, prioritizing the concerns of specific groups (such as women of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and disabled women) over the broader goal of gender equality. Critics argue that this fragmentation of the movement has led to infighting, division, and a loss of focus on the issues that unite all women. This argument, while superficially appealing, ignores the intersectional nature of oppression. Women are not a monolithic group; their experiences are shaped by a complex interplay of factors, including race, class, sexual orientation, and disability. To ignore these differences is to render invisible the unique challenges faced by marginalized women. Intersectionality isn’t a divisive force; it’s a recognition that justice for all requires addressing the specific needs of those who are most vulnerable.

Furthermore, the argument that feminism has become too focused on identity politics often serves as a convenient excuse to avoid addressing uncomfortable truths about power and privilege. It’s easy to declare that all women should be treated equally, but it’s far more challenging to confront the systemic inequalities that perpetuate racial disparities in healthcare, economic opportunities, and the criminal justice system. Feminism, at its best, is a movement for liberation for all, not just for those who already hold a position of privilege.

It is also said that modern feminism focuses on trivial issues, creating controversies where there are none. For example, the debate on the appropriateness of certain Halloween costumes, workplace dress codes, or the use of gendered language in certain contexts. To dismiss these concerns as trivial is to miss the larger point: that language and symbols matter. They shape our perceptions, reinforce stereotypes, and contribute to a culture of inequality. While the specific battles may seem small, they are part of a larger war against systemic bias and prejudice. Microaggressions, seemingly minor slights and insults, can have a cumulative effect, creating a hostile environment for marginalized groups. Addressing these issues isn’t about being overly sensitive or politically correct; it’s about creating a more inclusive and equitable society.

The critique that feminism has gone too far often stems from a misunderstanding of its core principles and a selective reading of its history. Feminism is not a static ideology; it’s a dynamic and evolving movement that is constantly adapting to the changing needs and challenges of the world. It’s not about achieving absolute equality in every sphere of life; it’s about dismantling the systemic barriers that prevent women from reaching their full potential. It’s not about hating men; it’s about creating a society where everyone, regardless of gender, can thrive. It’s not about suppressing dissent; it’s about amplifying the voices of the marginalized.

So, has feminism gone too far? Perhaps, in some instances, individual actions or pronouncements may have crossed the line. But to condemn the entire movement based on the actions of a few is to throw the baby out with the bathwater. The fight for gender equality is far from over. Women continue to face discrimination in the workplace, violence in their homes, and marginalization in the halls of power. The struggle continues. The demand for equality remains. The work is not yet complete.

The real question isn’t whether feminism has gone too far, but whether we, as a society, are willing to confront the uncomfortable truths about power, privilege, and the persistent inequalities that continue to shape our world. Are we willing to challenge the status quo, to dismantle the structures of oppression, and to create a future where everyone has the opportunity to thrive? If not, then perhaps the real problem isn’t that feminism has gone too far, but that we haven’t gone far enough.

Leave a Comment