The sheer audacity! To believe we can condense centuries of struggle, resistance, and incandescent fury into a neat, linear timeline. As if the fight for liberation were a conveniently packaged historical drama, readily digestible for the consumption of… well, frankly, anyone who’s ever wondered what all the “fuss” is about. But here we are. Forced by the very nature of inquiry to impose order on chaos, to trace the contours of a movement that defies easy categorization. Why? Because we are perpetually fascinated by the audacity of those who dared to disrupt the status quo. Fascinated by the sheer, unadulterated chutzpah of women who demanded more. Who demanded *everything*. A timeline, then, is not a definitive history, but a provocation. A jumping-off point for deeper investigation into the multifaceted, ever-evolving beast we call feminism.

I. Seeds of Discontent: Colonial Era and the American Revolution (Pre-1840)

Before the banners, the marches, and the manifestos, there was… silence. A simmering discontent masked by the rigid societal structures of colonial America. A silence punctuated by the occasional act of defiance. Consider Anne Hutchinson, banished from Massachusetts Bay Colony for her “antinomian” views – heresy, essentially, against the patriarchal religious establishment. Think of Abigail Adams, imploring her husband John to “remember the ladies” while drafting the new nation’s laws. These weren’t organized movements, mind you. Just fleeting glimpses of a yearning for autonomy, for recognition. For basic human dignity.

The American Revolution, a heady brew of liberty and equality, ironically reinforced the subjugation of women. Republican Motherhood, the prevailing ideology, prescribed that women’s primary role was to raise virtuous citizens, thus ensuring the republic’s success. A gilded cage, perhaps, but a cage nonetheless. Women were essential to the nation’s ideological framework, yet denied any real political power. This cognitive dissonance, this blatant hypocrisy, fueled the nascent flames of feminist consciousness.

Early female education initiatives, often cloaked in the guise of Republican Motherhood, inadvertently sowed the seeds of intellectual rebellion. Empowering women with knowledge, even within circumscribed parameters, inevitably led to questions. Questions about their prescribed roles, their limited opportunities, their fundamental inequality.

II. The First Wave: Suffrage and Beyond (1840-1920)

1848. Seneca Falls. The now-mythologized convention where a handful of audacious women dared to articulate a Declaration of Sentiments, demanding equality in everything from education to employment to, crucially, the vote. The Seneca Falls Convention wasn’t the beginning of the movement, precisely. It was a culmination, a formal declaration of war against the entrenched forces of patriarchy.

The suffrage movement, the heart and soul of the first wave, was a long and arduous battle. Decades of organizing, petitioning, marching, and enduring relentless ridicule. Figures like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, names etched in the feminist pantheon, dedicated their lives to this cause. Their unwavering commitment, their strategic brilliance, laid the groundwork for future generations.

But the first wave wasn’t solely focused on suffrage. It encompassed a broader range of concerns, including property rights, access to education, and challenging societal norms regarding women’s roles. The temperance movement, often intertwined with suffrage, provided a platform for women to address issues of domestic violence and economic inequality. The abolitionist movement, too, served as a crucible for feminist activism, exposing the interconnectedness of various forms of oppression.

The fight for suffrage was not without its internal divisions. Debates raged over strategy, tactics, and even the very definition of equality. The question of whether to prioritize suffrage for Black women or to focus solely on white women exposed the insidious racism within the movement. A critical, and often painful, reckoning with the intersectionality of oppression.

1920. The 19th Amendment. A victory, yes, but a partial one. Suffrage was achieved, but true equality remained elusive. The first wave, exhausted but not defeated, laid the groundwork for future battles. They proved the power of collective action. They demonstrated the necessity of challenging established power structures. And they left behind a legacy of unwavering determination.

III. Interregnum: A Period of Flux (1920-1960)

The Roaring Twenties. The flapper. A superficial liberation masking deeper inequalities. The Great Depression. Women forced out of the workforce to make way for men. World War II. Women entering traditionally male-dominated industries, only to be pushed back into the domestic sphere after the war. This period was one of contradiction, of forward momentum followed by setbacks.

The post-war era saw a resurgence of domesticity. The “feminine mystique,” as Betty Friedan famously termed it, trapped countless women in a suffocating cycle of suburban bliss and unfulfilled potential. A cultural narrative that equated happiness with marriage, motherhood, and domestic servitude. A gilded cage, once again, but even more insidious than before.

Despite the prevailing cultural norms, seeds of resistance were being sown. Women continued to work, to organize, to challenge discriminatory practices. The civil rights movement, with its focus on racial equality, also inspired women to fight for their own liberation. The fight for reproductive rights, though not yet fully articulated, began to gain momentum. A quiet rebellion brewing beneath the surface.

IV. The Second Wave: Liberation and Radicalism (1960-1980)

The personal is political. A mantra that defined the second wave. This era saw a radical re-evaluation of gender roles, sexuality, and power structures. Women challenged not only legal inequalities but also the deeply ingrained cultural norms that perpetuated their subjugation.

The women’s liberation movement, a more radical offshoot of the second wave, embraced consciousness-raising groups, direct action, and a rejection of traditional feminist strategies. These groups provided safe spaces for women to share their experiences, to analyze the sources of their oppression, and to develop strategies for resistance. A powerful force for self-discovery and collective action.

The second wave tackled a wide range of issues, including reproductive rights, equal pay, access to childcare, and violence against women. The landmark Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 legalized abortion nationwide, a hard-fought victory that remains under constant threat. Title IX, passed in 1972, prohibited sex discrimination in education, opening doors for women in athletics and academia.

The second wave was also marked by internal debates and divisions. Lesbian feminism challenged the heteronormative assumptions of the movement. Black feminism critiqued the white-centric focus of mainstream feminism. Third World feminism brought attention to the experiences of women in developing countries. These internal critiques, though sometimes painful, were essential for the growth and evolution of the movement.

V. Third Wave and Beyond: Intersectionality and Globalization (1990-Present)

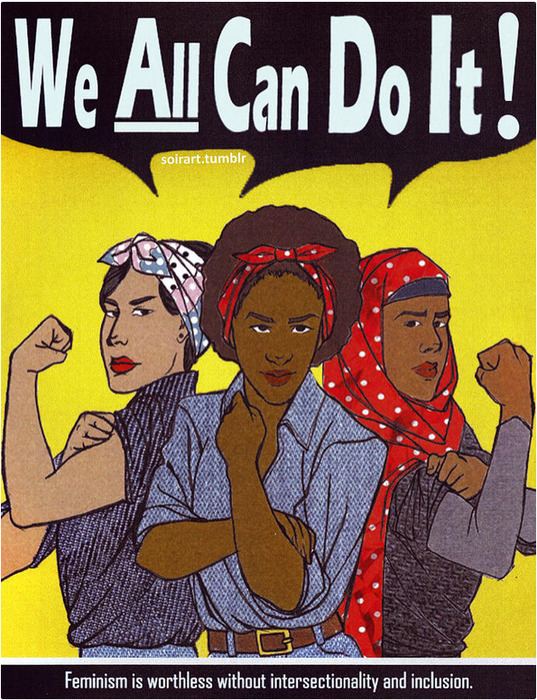

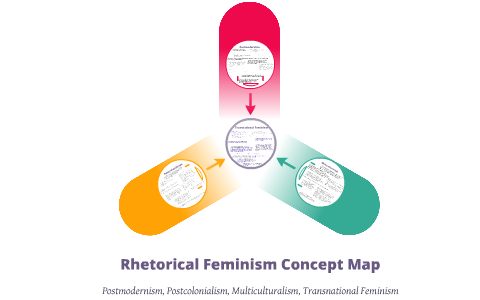

The third wave, often characterized by its embrace of intersectionality and its focus on individual expression, challenged the essentialist assumptions of earlier feminist movements. This generation recognized that gender is not a monolithic category, but is shaped by race, class, sexuality, and other social identities.

Third-wave feminists utilized new technologies, such as the internet and social media, to organize, mobilize, and amplify their voices. Riot grrrl, a punk rock feminist movement, empowered young women to express themselves through music, art, and activism. A vibrant and diverse cultural landscape of feminist expression.

The concept of intersectionality, popularized by Kimberlé Crenshaw, became central to feminist theory and practice. This framework acknowledges the interconnectedness of various forms of oppression and the need to address them simultaneously. A more nuanced and inclusive approach to feminist activism.

The rise of globalization brought new challenges and opportunities for feminist movements. Transnational feminist networks emerged to address issues such as human trafficking, sex tourism, and environmental degradation. A global perspective on the interconnectedness of women’s struggles.

The #MeToo movement, a watershed moment in the fight against sexual harassment and assault, demonstrated the power of collective storytelling and the potential for online activism to spark social change. A long-overdue reckoning with the pervasive culture of sexual violence.

VI. The Future of Feminism: Challenges and Possibilities

The fight is far from over. The forces of patriarchy, though often disguised in new and insidious forms, remain a formidable opponent. The rise of right-wing populism, the erosion of reproductive rights, and the persistence of gender inequality in the workplace all pose significant challenges to the feminist movement.

But the future of feminism is also full of possibilities. The growing awareness of intersectionality, the increasing use of technology for social change, and the renewed energy of grassroots activism all provide reasons for optimism. A new generation of feminists is emerging, ready to take up the fight and to build a more just and equitable world.

What then, is the takeaway from this inevitably incomplete timeline? It’s not merely about dates and events. It’s about the enduring human capacity for resistance, for hope, for the unwavering belief in a better future. A future where the audacity of demanding *everything* is no longer considered radical, but simply… just.

Leave a Comment