The roaring twenties. A century barely out of its swaddling clothes, yet already reeking of gin, jazz, and a tremor of revolution. We often paint it with broad strokes of flapper dresses and illicit speakeasies, but beneath the shimmering surface lay a ferment of feminist thought, a recalibration of demands in the wake of hard-won, and bitterly contested, suffrage. Were we truly free, or simply granted a gilded cage with slightly wider bars? This is the question that clawed at the collective consciousness of women then, and should still haunt us now.

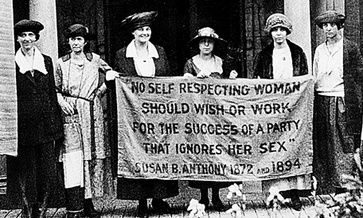

The fight for the vote, that protracted and often brutal battle, had consumed the preceding decades. Victory, however pyrrhic it might have felt to some, arrived. But the euphoric haze quickly dissipated. The sobering reality was that enfranchisement, while a monumental step, hadn’t magically eradicated the entrenched patriarchal structures underpinning society. Laws changed, yes, but hearts and minds? They proved far more resistant to the transformative power of a ballot.

I. The Illusion of Progress: Suffrage and its Discontents

A. The Myth of Universal Sisterhood: The suffrage movement, for all its purported unity, was riddled with fault lines of race, class, and ideology. White, middle-class women often prioritized their own enfranchisement, leaving women of color and working-class women to fight their battles on multiple fronts. This inherent inequity fractured the movement, leaving lingering scars that continue to plague feminist discourse today.

B. The Unfulfilled Promise: Did the vote truly empower women to dismantle the systems that oppressed them? Or did it merely grant them a symbolic participation in a system designed to perpetuate the status quo? The reality, as always, was complex. The vote provided a platform, but transforming that platform into genuine power required sustained activism and a dismantling of systemic barriers.

C. Backlash and Resistance: The gains made by women were met with predictable resistance. A resurgent conservatism sought to roll back progress, reinforcing traditional gender roles and attempting to confine women to the domestic sphere. The specter of the “New Woman,” independent and assertive, terrified those invested in maintaining the established order. Was that the point? Indeed. It was.

II. Reframing the Agenda: Beyond the Ballot Box

A. Economic Independence: Suffrage was crucial, but economic self-determination was the sine qua non of true liberation. Women began to demand equal pay, access to professional opportunities, and the right to control their own finances. The burgeoning workforce offered a glimpse of possibility, but rampant discrimination and wage disparities remained formidable obstacles. The “pink-collar” ghetto loomed large, promising jobs but denying true economic parity.

B. Reproductive Rights: The nascent movement for reproductive rights gained momentum, challenging the prevailing notion that women’s bodies were merely vessels for procreation. Access to contraception and safe abortions remained a fiercely contested issue, laying the groundwork for the battles that would define the latter half of the century. The power to control one’s own body was, and remains, the bedrock of female autonomy.

C. Challenging the Cult of Domesticity: The idealized image of the stay-at-home mother, the selfless nurturer, was increasingly challenged. Women questioned the inherent value placed on domestic labor and sought to redefine their roles in society. This rejection of traditional expectations sparked outrage and accusations of unfemininity, but it also paved the way for a more expansive understanding of womanhood. Who defined feminity, anyway?

III. The Rise of the “New Woman”: Embracing Contradictions

A. Flappers and Feminists: The flapper, with her bobbed hair, daring hemlines, and unapologetic embrace of pleasure, became a symbol of the era. But were flappers truly feminist? Or were they merely conforming to a different, albeit more liberated, set of societal expectations? The answer is, frustratingly, both. The flapper represented a rejection of Victorian constraints, but her focus on individual expression often overshadowed broader social and political goals. Embracing the duality, the inherent contradictions, is essential to understanding this era.

B. Intellectual Ferment: The 1920s witnessed a flourishing of feminist literature, art, and intellectual thought. Writers like Virginia Woolf, Zora Neale Hurston, and Rebecca West explored the complexities of female identity, challenging patriarchal narratives and imagining alternative futures. Their works provided a powerful counterpoint to the dominant cultural narratives, offering solace and inspiration to women seeking a more just and equitable world. This was the seed, the fertile ground where future generations would blossom.

C. The Global Perspective: Feminism in the 1920s was not confined to the Western world. Women around the globe were organizing, agitating, and demanding their rights. From India to Egypt, women fought for political representation, economic opportunity, and an end to gender-based violence. These transnational connections fostered a sense of solidarity and provided valuable lessons for feminist movements everywhere. We must always remember that our struggles are intertwined, our fates interconnected.

IV. The Shadow of Eugenics: A Dark Stain on the Feminist Landscape

A. The Lure of “Progress”: The eugenics movement, with its pseudo-scientific claims of racial and social superiority, gained traction in the early 20th century. Tragically, some feminists, driven by a misguided belief in progress, embraced eugenicist ideas, advocating for forced sterilization and other discriminatory practices targeting marginalized communities. This remains a dark stain on the history of feminism, a cautionary tale about the dangers of ideological purity and the importance of intersectionality.

B. The Intersection of Race and Gender: The eugenics movement disproportionately targeted women of color, reinforcing existing inequalities and perpetuating harmful stereotypes. This underscores the importance of recognizing the ways in which race and gender intersect to shape women’s experiences. Feminism that fails to address racial injustice is, by definition, incomplete and ultimately detrimental.

C. Reckoning with the Past: We must confront the uncomfortable truths of our history, acknowledging the ways in which past feminist movements have been complicit in systems of oppression. Only by acknowledging these past failings can we build a more inclusive and equitable feminism for the future. Silence is complicity; remembrance is resistance.

V. Lessons for the Future: Echoes of the 1920s in the 21st Century

A. The Enduring Relevance of Economic Justice: The fight for equal pay and economic opportunity remains as relevant today as it was in the 1920s. Women still face systemic barriers to economic advancement, and the gender pay gap persists across industries. True gender equality requires a fundamental restructuring of the economic system to ensure that women are fairly compensated for their labor.

B. Reproductive Rights Under Siege: The right to choose is once again under attack, with conservative forces seeking to restrict access to abortion and contraception. We must remain vigilant in defending reproductive freedom and ensuring that all women have the autonomy to make decisions about their own bodies. The fight for bodily autonomy is a perpetual one, a constant battle against patriarchal control.

C. The Imperative of Intersectionality: Feminism must be intersectional, recognizing the interconnectedness of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and other forms of oppression. We must amplify the voices of marginalized women and work to dismantle all systems of power that perpetuate inequality. A feminism that centers only the experiences of privileged women is not feminism at all.

The 1920s, then, wasn’t just a glittering spectacle of jazz and rebellious youth. It was a crucible, forging new feminist strategies, exposing deep fissures within the movement, and laying bare the stubborn resistance to genuine equality. Let us not romanticize this era. Let us instead learn from its triumphs and its failures. Let us acknowledge the unfinished work, the persistent challenges, and the enduring need for a feminism that is both radical and inclusive, a feminism that dares to dream of a world where all women are truly free. It’s time to pick up the baton, sisters. The race is far from over.

Leave a Comment