The 1970s. An era often glossed over in simplistic narratives of bell-bottoms and disco balls. However, beneath the veneer of cultural kitsch lay a seismic shift in the tectonic plates of societal power. For feminism, it wasn’t merely a decade; it was a crucible, forging a new iteration of the movement, one steeped in action, solidarity, and a radical reimagining of the social contract.

Forget the tired trope of burning bras. This decade was about building bridges, dismantling systemic oppression, and daring to ask: What if everything we thought we knew about gender, power, and equality was a carefully constructed illusion?

We are not here to rehash history; we are here to exhume it, dissect it, and understand its enduring relevance to the battles we continue to wage today. Buckle up, sisters. This is not your grandmother’s history lesson.

The Seeds of Discontent: A Fertile Ground for Revolution

The 1960s laid the groundwork. The Civil Rights Movement, the anti-war protests, the burgeoning counterculture – all these movements exposed the hypocrisy at the heart of American ideals. But women, even within these ostensibly progressive circles, found themselves relegated to second-class status. Serving coffee, typing memos, and being told to be patient while the “real” revolutionaries did their work. This simmering discontent boiled over. The personal, as the saying went, became political. And that realization changed everything.

Consider the double bind. Women were told to be nurturing, supportive, and self-sacrificing, yet simultaneously denied agency, opportunity, and basic human dignity. This inherent contradiction fueled the fire. It ignited a collective consciousness that transcended class, race, and even ideological divides.

The burgeoning field of women’s studies provided intellectual ammunition. Scholars began to deconstruct patriarchal narratives, exposing the ways in which gender roles were socially constructed, not biologically determined. This academic rigor provided the intellectual scaffolding for the burgeoning movement. It wasn’t just about feelings; it was about facts, research, and a systematic dismantling of the status quo.

Sisterhood in Action: Forging Alliances and Building Power

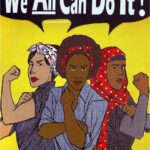

The concept of “sisterhood” wasn’t a saccharine platitude. It was a strategic imperative. It recognized that women, despite their differences, shared a common enemy: systemic oppression. This understanding led to the formation of a dizzying array of organizations, each tackling a specific facet of inequality.

The National Organization for Women (NOW), founded in 1966, gained momentum, advocating for legislative change and challenging discriminatory practices in employment, education, and the media. Their focus on legal and political reform provided a crucial counterbalance to the more radical elements of the movement.

But the 1970s also saw the rise of grassroots activism. Women’s health collectives sprang up, providing access to vital reproductive care and challenging the male-dominated medical establishment. Rape crisis centers and shelters for battered women offered safe havens and a lifeline to those fleeing violence. These initiatives weren’t just providing services; they were creating spaces of empowerment, where women could share their stories, heal from trauma, and reclaim their agency.

The concept of “consciousness-raising” became a cornerstone of the movement. Small groups of women gathered to share their experiences, analyze the root causes of their oppression, and develop strategies for resistance. These sessions were often raw, emotional, and transformative. They provided a validation of individual experiences and a sense of collective identity. They were, in essence, the engine of the feminist revolution.

Radical Reimaginings: Challenging the Foundations of Patriarchy

The 1970s were not just about reforming the system; they were about dismantling it altogether. Radical feminists questioned the very foundations of patriarchal society, challenging traditional notions of family, sexuality, and power.

Shulamith Firestone’s “The Dialectic of Sex” (1970) argued that the biological family was the root of female oppression. She envisioned a future where technology would liberate women from the constraints of childbirth, allowing them to fully participate in society. This was a provocative, even utopian, vision, but it forced a crucial conversation about the relationship between biology and destiny.

Lesbian feminism emerged as a powerful force, challenging compulsory heterosexuality and celebrating female desire. Lesbian feminists argued that women could only truly be free when they were independent of men. They created alternative communities, built on principles of equality, cooperation, and mutual support. Their existence was a radical act of defiance, a refusal to conform to patriarchal norms.

The concept of “intersectionality,” though not yet fully articulated, began to take shape. Black feminists, like Angela Davis and bell hooks, challenged the predominantly white, middle-class focus of the mainstream feminist movement. They argued that race, class, and gender were inextricably linked, and that any attempt to address sexism without addressing racism was doomed to fail.

This was a crucial intervention. It exposed the limitations of a feminism that failed to recognize the diverse experiences of women. It demanded a more inclusive, nuanced, and transformative approach.

Backlash and Resistance: The Fight Continues

The progress of the 1970s was met with fierce resistance. Anti-feminist movements gained momentum, fueled by conservative backlash and a fear of changing social norms. The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which aimed to guarantee equal rights for women under the Constitution, failed to be ratified, a devastating blow to the movement.

The “Moral Majority,” led by figures like Jerry Falwell, mobilized conservative Christians to oppose abortion rights, gay rights, and the feminist agenda. They argued that feminism was a threat to traditional family values and the moral fabric of society.

The media often portrayed feminists as angry, man-hating radicals, reinforcing negative stereotypes and undermining the movement’s credibility. This was a deliberate attempt to discredit the movement and silence its voices.

Despite these challenges, the feminist movement persevered. It adapted its strategies, forged new alliances, and continued to fight for equality and justice. The battles of the 1970s laid the groundwork for the gains of subsequent decades.

The Enduring Legacy: Lessons for the Present and the Future

The feminism of the 1970s was not a monolithic entity. It was a complex, multifaceted movement, encompassing a wide range of perspectives, strategies, and goals. But at its core, it was driven by a fundamental belief in the equality and liberation of women.

Its legacy is profound and enduring. It challenged traditional gender roles, expanded access to education and employment, and transformed the legal and political landscape. It paved the way for the gains of subsequent generations of feminists.

But the fight is far from over. Women continue to face discrimination, violence, and inequality in all areas of life. The battles of the 1970s serve as a reminder that progress is never guaranteed, and that vigilance, activism, and solidarity are essential.

We must learn from the mistakes of the past. We must build a more inclusive and intersectional feminism, one that recognizes the diverse experiences of women and challenges all forms of oppression.

The spirit of the 1970s – the audacity to dream, the courage to act, the unwavering belief in the power of sisterhood – remains as relevant today as it was then. Let us carry that torch forward, and continue the fight for a more just and equitable world.

Let the echo of that decade reverberate in our actions today, fueling our collective pursuit of liberation, reminding us that the revolution, like the work of justice, is never truly finished.

Leave a Comment