Why this incessant fascination with the First Wave? Is it the sepia-toned photographs, the quaint bonnets, the seemingly simpler demands? Perhaps it’s the deceptive allure of a movement painted in strokes of Victorian morality, a stark contrast to the kaleidoscopic, intersectional battleground feminism has become today. But scratch the surface, and you’ll find a roiling cauldron of discontent, a seismic shift in the tectonic plates of patriarchal power, and a lineage of radicalism that still resonates, however faintly, in our contemporary struggles.

The First Wave, generally understood as spanning from the mid-19th century to the early 20th, wasn’t just about suffrage. It was about challenging the very edifice upon which female subjugation was built: the cult of domesticity. This insidious ideology, prevalent in Western societies, confined women to the private sphere, casting them as angels in the house, paragons of virtue, and, crucially, intellectually inferior beings incapable of participating in the public arena. This wasn’t just about restricting their vote; it was about restricting their minds, their bodies, and their very potential.

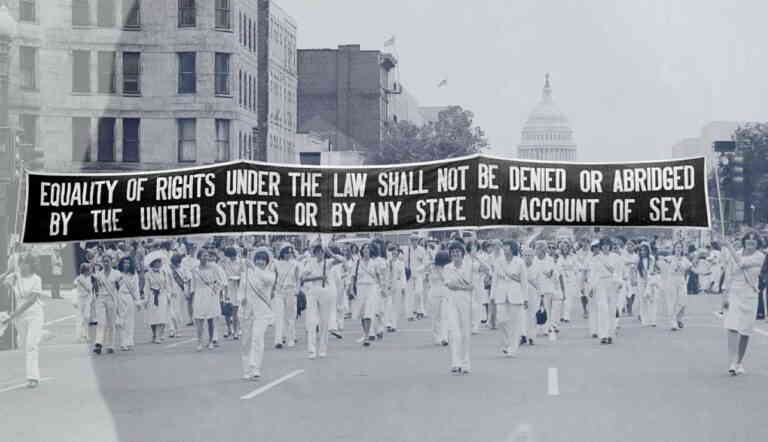

I. The Suffrage Scuffle: More Than Just a Ballot

The fight for suffrage undoubtedly occupied center stage. Icons like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, names etched in the annals of feminist history, tirelessly campaigned for the franchise. But to reduce their efforts to merely securing the vote is a gross simplification. The ballot was a wedge, a tool to dismantle the legal and social structures that systematically disenfranchised women.

A. Coverture and its Corsets: Consider the legal doctrine of coverture, where a married woman’s legal existence was subsumed by her husband. She couldn’t own property, enter into contracts, or even control her own earnings. Suffrage, therefore, was not just about political representation; it was about attaining basic legal personhood, about clawing back a semblance of autonomy from the suffocating embrace of marital law.

B. The “Republican Motherhood” Gambit: The movement cleverly exploited the prevailing notion of “Republican Motherhood,” which argued that women, as the primary educators of future citizens, had a vested interest in the political health of the nation. By positioning themselves as morally superior and uniquely equipped to instill civic virtue, suffragists subtly challenged the patriarchal narrative that relegated them to the realm of frivolous pursuits. The brilliance of this strategy lay in using the very ideology that confined them to make a case for their political enfranchisement.

C. Divisions and Dissensions: However, the suffrage movement was far from monolithic. Deep divisions existed regarding strategy, tactics, and, most troublingly, race. The National Woman Suffrage Association, led by Anthony and Stanton, initially prioritized the enfranchisement of white women, often employing rhetoric that was explicitly racist and nativist. This blatant disregard for the experiences of Black women, who faced the double burden of sexism and racism, remains a stain on the First Wave’s legacy, a stark reminder of the intersectional blind spots that plagued the movement.

II. Education as Emancipation: Unlocking the Female Intellect

Beyond the ballot box, First Wave feminists recognized the transformative power of education. Access to higher education was seen as a crucial pathway to economic independence and intellectual liberation. It was an affront to the prevailing notion that women were intellectually incapable of mastering complex subjects.

A. The Rise of Women’s Colleges: Institutions like Vassar, Smith, and Wellesley emerged as bastions of female intellectualism, providing women with a rigorous education that rivaled that of their male counterparts. These colleges weren’t just about imparting knowledge; they were about fostering a sense of female community and empowerment, creating spaces where women could explore their potential without the constraints of societal expectations.

B. Challenging the “Neurasthenia” Narrative: The medical establishment of the time often pathologized female ambition, diagnosing women who pursued intellectual or professional endeavors with “neurasthenia,” a catch-all term for nervous exhaustion. First Wave feminists actively challenged this narrative, arguing that female intellect was not a disease to be cured but a faculty to be cultivated.

C. Careers Beyond the Hearth: Armed with education, women began to enter professions previously considered exclusively male domains, such as medicine, law, and journalism. These pioneering women faced immense resistance and discrimination, but their persistence paved the way for future generations of female professionals.

III. Bodily Autonomy: Reclaiming Control Over Reproduction

The issue of bodily autonomy, while not as explicitly articulated as in later waves of feminism, was nonetheless a simmering undercurrent in the First Wave. The Comstock Laws, enacted in 1873, criminalized the distribution of information about contraception and abortion, effectively denying women control over their reproductive lives.

A. The “Social Purity” Movement: While seemingly conservative on the surface, the Social Purity movement, which advocated for abstinence and sexual morality, also contained a radical undercurrent of female empowerment. By demanding that men adhere to the same standards of sexual conduct as women, the movement subtly challenged the patriarchal double standard that held women solely responsible for maintaining sexual morality.

B. Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Crusade: Margaret Sanger, a pivotal figure in the fight for reproductive rights, emerged in the later years of the First Wave. Her tireless advocacy for birth control, despite facing legal persecution and societal condemnation, laid the groundwork for the reproductive rights movement that would gain momentum in the following decades. Her work was a defiant act of rebellion against laws that sought to control women’s bodies and destinies.

C. The Eugenics Shadow: It is crucial to acknowledge the problematic intersection of the birth control movement and the eugenics movement of the time. Some proponents of birth control, including Sanger, were influenced by eugenic ideas, advocating for the sterilization of individuals deemed “unfit” to reproduce. This dark chapter in the history of reproductive rights serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of allowing discriminatory ideologies to infiltrate feminist movements.

IV. The Personal is Political (Even Then): Challenging Domestic Tyranny

Although the phrase “the personal is political” is most closely associated with Second Wave feminism, the seeds of this concept were sown during the First Wave. The domestic sphere, far from being a haven of tranquility, was often a site of oppression, where women were subjected to the whims of their husbands and denied basic rights.

A. Challenging the Cult of Domesticity: First Wave feminists directly challenged the cult of domesticity, arguing that women’s roles should not be limited to the home and that they deserved opportunities to pursue their own ambitions and interests. This wasn’t just about career aspirations; it was about rejecting the notion that women’s worth was solely determined by their ability to manage a household and raise children.

B. Divorce Reform: The fight for divorce reform was another crucial aspect of challenging domestic tyranny. Laws made it exceedingly difficult for women to escape abusive or unhappy marriages. First Wave feminists advocated for more equitable divorce laws, recognizing that women deserved the right to leave marriages that were detrimental to their well-being.

C. Suffrage and the Temperance Movement: The complex relationship between the suffrage movement and the temperance movement reveals the multifaceted nature of First Wave feminism. While some feminists supported temperance as a means of protecting women and children from the harms of male alcoholism, others viewed it as a patriarchal attempt to control male behavior and restrict individual liberty. This alliance highlights the inherent tensions and contradictions within the movement.

V. The Legacy Endures: Echoes in the Present

While the First Wave ostensibly achieved its primary goal of securing suffrage with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, its legacy extends far beyond the ballot box. It laid the groundwork for subsequent waves of feminism by challenging fundamental assumptions about gender roles, demanding access to education and economic opportunities, and advocating for bodily autonomy.

A. The Unfinished Revolution: The struggles of First Wave feminists resonate even today. The fight for equal pay, reproductive rights, and an end to gender-based violence remains ongoing. Their sacrifices and achievements serve as a constant reminder of the progress that has been made and the work that still needs to be done.

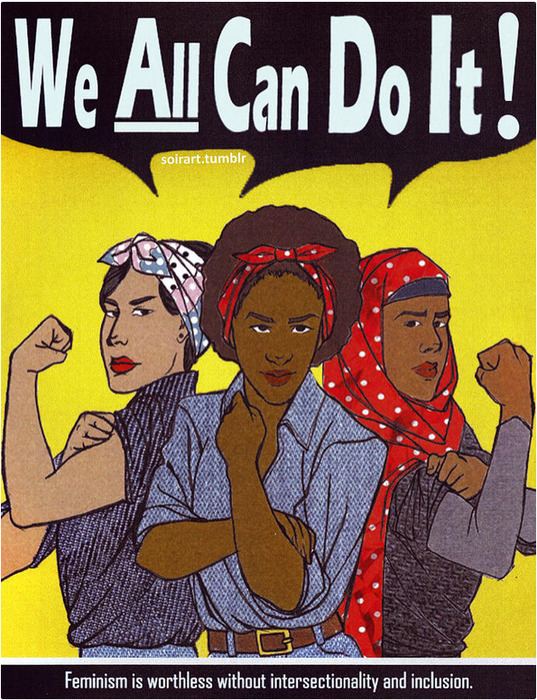

B. Intersectionality Revisited: The First Wave’s blind spots regarding race and class serve as a cautionary tale for contemporary feminists. The need to center the experiences of marginalized women and to address the interconnected systems of oppression remains paramount.

C. Beyond the Binary: While the First Wave largely focused on the binary of male and female, contemporary feminism recognizes the fluidity of gender identity and embraces the experiences of transgender and non-binary individuals. This is a crucial evolution, a broadening of the feminist tent to include all those who experience gender-based oppression.

The First Wave wasn’t a quaint, sepia-toned relic of the past. It was a fierce, messy, and often contradictory movement that challenged the very foundations of patriarchal power. Its flaws are undeniable, but its achievements are undeniable too. By understanding its complexities and its contradictions, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the long and arduous journey towards gender equality and a renewed commitment to the ongoing struggle for liberation.

Leave a Comment