Why are young minds, grappling with the rise and fall of empires, the clash of civilizations, and the relentless march of time itself, so often captivated by the notion of feminism in AP World History? Is it merely a matter of ticking boxes on a curriculum checklist, a perfunctory nod to “gender balance”? Or does this fascination hint at something far more profound, a yearning to understand the intricate ways power, oppression, and resistance have shaped the human experience for half of the population across millennia?

The reality, of course, is multifaceted. The study of feminism within a global historical context offers a compelling lens through which to examine the very foundations of societal structures. It challenges the pervasive androcentric biases that have historically dominated narratives, forcing a reassessment of what constitutes “important” history and who gets to write it. By interrogating the roles, rights, and realities of women across diverse cultures and time periods, students can begin to deconstruct the patriarchal scaffolding that has long underpinned global power dynamics. This isn’t just about adding women to the narrative; it’s about fundamentally reshaping the narrative itself.

Let us unpack this further with an extensive exploration. We must move beyond simple definitions and surface-level analyses, delving into the complexities and nuances of feminist thought within the historical tapestry. The goal? To equip students with the critical tools necessary to navigate the ongoing struggles for gender equality around the world.

I. Defining Feminism: A Moving Target

Defining “feminism” itself presents a challenge. It is not a monolithic ideology, but rather a constellation of diverse and often conflicting perspectives. To provide a comprehensive overview, we must consider its key tenets.

A. Core Principles

At its heart, feminism is fundamentally about challenging gender inequality. It presupposes the belief that women are systematically disadvantaged due to their gender and advocates for social, political, and economic equality. This encompasses a wide range of concerns, from reproductive rights and equal pay to combating violence against women and challenging harmful gender stereotypes. However, the specific ways in which these principles are applied and prioritized vary significantly across different feminist perspectives.

B. Waves of Feminism: A Historical Overview

The traditional “waves” model of feminism provides a useful, though admittedly imperfect, framework for understanding the evolution of feminist thought. Each wave has grappled with different sets of issues and has been shaped by its specific historical context.

1. First-Wave Feminism (Late 19th – Early 20th Century): Primarily focused on legal and political rights, particularly the right to vote. Suffragettes, such as those in Britain and the United States, fought tirelessly for enfranchisement. The core issue revolved around legal personhood and the formal recognition of women as citizens.

2. Second-Wave Feminism (1960s – 1980s): Expanded the scope of feminist concerns to include issues of sexuality, reproductive rights, workplace equality, and domestic violence. Influenced by the Civil Rights Movement and other social justice movements, second-wave feminists challenged traditional gender roles and sought to dismantle patriarchal structures in all aspects of life. The slogan “the personal is political” became a rallying cry, highlighting the ways in which private experiences are shaped by systemic power dynamics.

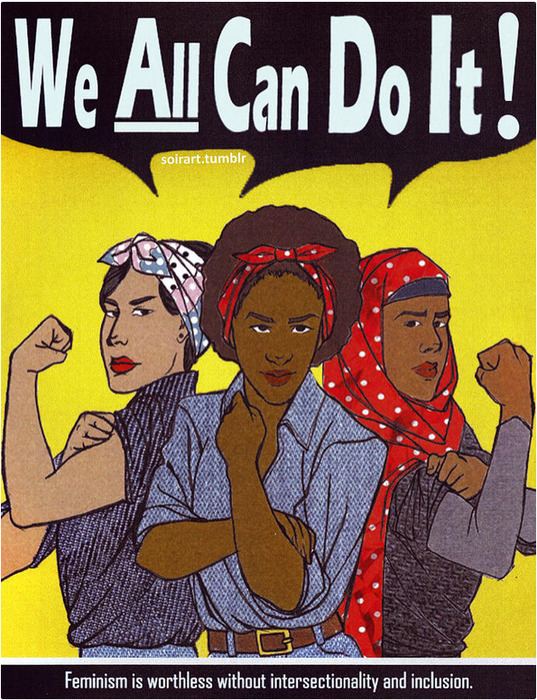

3. Third-Wave Feminism (1990s – Present): Embraces diversity and intersectionality, recognizing that gender intersects with other forms of oppression, such as race, class, sexual orientation, and disability. Third-wave feminists challenge essentialist notions of womanhood and celebrate individual agency and self-expression. They often utilize digital platforms and media to amplify marginalized voices and promote social change. Critiques of second-wave feminism’s perceived focus on the experiences of white, middle-class women are central to this wave.

C. Global Feminisms: Beyond the Western Lens

The traditional “waves” model, while helpful, is often critiqued for its Western-centric bias. Global feminisms recognize that feminism manifests differently in various cultural contexts. It resists universalizing the experiences of Western women and acknowledges the diverse challenges faced by women around the world. For instance, feminist movements in post-colonial societies often grapple with the legacy of colonialism and the intersection of gender with national identity and cultural preservation. Furthermore, economic globalization has created new forms of exploitation that feminist activists must address. Considerations for issues such as access to education in some nations must take precedent.

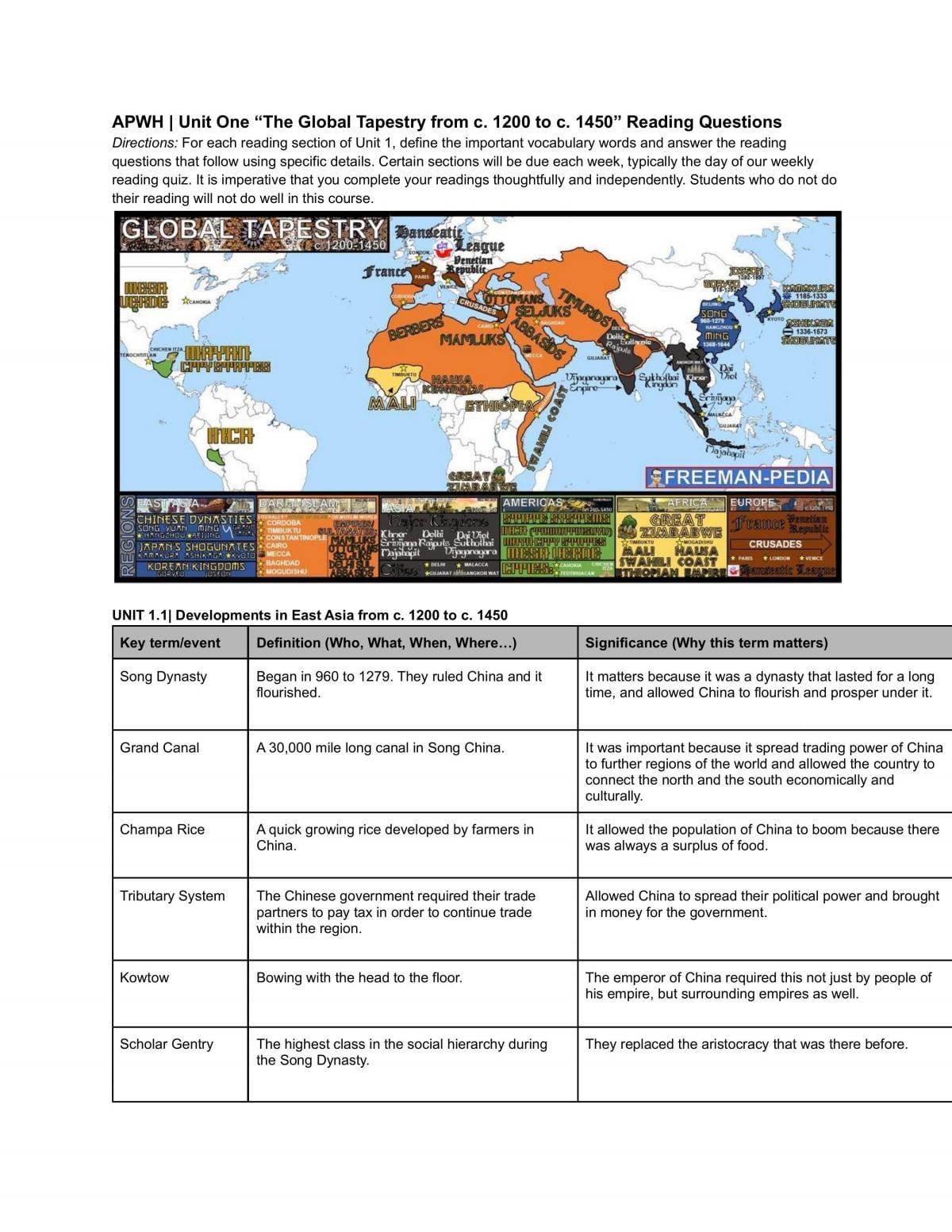

II. Feminism in AP World History: Key Themes and Topics

Now, let’s examine how feminism manifests across various time periods and geographical regions within the AP World History curriculum. Students should be equipped to identify and analyze these themes.

A. Gender Roles and Social Structures

Understanding the historical construction of gender roles is crucial. This involves examining how different societies have defined masculinity and femininity and how these definitions have shaped social structures. For example, in some agrarian societies, women played a vital role in agricultural production, granting them a degree of economic autonomy. Conversely, in other societies, women were relegated to the domestic sphere and denied access to education and property ownership. The key is to move beyond simplistic binaries and recognize the diversity of gender roles across cultures.

B. Women and Power

While women have historically been excluded from formal positions of power, they have often wielded influence in other ways. Examining women’s participation in religious movements, economic activities, and political intrigues can reveal the multifaceted nature of female power. Examples include female rulers like Hatshepsut in ancient Egypt or Empress Wu Zetian in Tang Dynasty China, who challenged traditional gender norms and exercised significant political authority. Furthermore, even when excluded from formal political institutions, women have often exerted influence through informal networks and social movements.

C. Women and Labor

Women’s labor has been essential to the functioning of economies throughout history. However, their contributions have often been undervalued or rendered invisible. Examining women’s participation in agriculture, manufacturing, trade, and domestic work can shed light on the complex relationship between gender and economic development. The Industrial Revolution, for example, led to new forms of female labor, but also exposed women to exploitation and dangerous working conditions. Students should be able to analyze the ways in which economic systems have shaped women’s lives and opportunities.

D. Women and Religion

Religion has played a complex and often contradictory role in shaping women’s lives. On one hand, some religious traditions have been used to justify the subordination of women. On the other hand, religion has also provided women with a source of empowerment and community. Examining the role of women in different religious traditions, from priestesses in ancient societies to female mystics in medieval Europe to contemporary feminist theologians, can reveal the diverse ways in which women have engaged with the spiritual realm.

E. Women and Resistance

Throughout history, women have actively resisted oppression in various forms. This includes participation in rebellions, social movements, and acts of everyday resistance. Examining the strategies and tactics used by women to challenge patriarchal structures can provide insights into the dynamics of power and resistance. The anti-slavery movement, for example, saw the rise of prominent female abolitionists like Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, who challenged both slavery and gender inequality. These movements demonstrate that resistance can take many forms, from overt political action to subtle acts of defiance.

III. Challenges and Nuances

Teaching feminism in AP World History is not without its challenges. It requires sensitivity, critical thinking, and a willingness to engage with complex and often uncomfortable topics. Some potential pitfalls include:

A. Avoiding Essentialism

It’s important to avoid essentializing women or assuming that all women share the same experiences. Feminism recognizes the diversity of women’s lives and the ways in which gender intersects with other forms of identity. Students should be encouraged to analyze the specific historical and cultural contexts that shape women’s experiences, rather than relying on sweeping generalizations.

B. Recognizing Agency

While acknowledging the systemic oppression faced by women, it’s equally important to recognize their agency and resilience. Women are not simply passive victims of history. They are active agents who have shaped their own lives and fought for social change. Students should be encouraged to identify and analyze the ways in which women have exercised agency, even in the face of adversity.

C. Addressing Cultural Relativism

Examining gender roles in different cultures can raise difficult questions about cultural relativism. It’s important to avoid imposing Western values on other cultures while also recognizing the universality of certain human rights. Students should be encouraged to engage in critical dialogue about the ethical implications of cultural practices and the potential for cultural change.

IV. Conclusion: Why Feminism Matters in World History

Ultimately, the study of feminism in AP World History is not just about learning about women’s history; it’s about gaining a deeper understanding of the complexities of power, oppression, and resistance throughout human history. By challenging androcentric biases and interrogating patriarchal structures, students can develop the critical thinking skills necessary to navigate the ongoing struggles for gender equality around the world. The incorporation of feminist perspectives offers a more nuanced and complete understanding of the human experience, moving beyond traditional narratives that often overlook or marginalize the contributions of women. It demands a re-evaluation of historical events and an acknowledgment of the diverse perspectives that shape our world. Embracing this challenge allows students to become more informed, empathetic, and engaged citizens, equipped to contribute to a more just and equitable future for all.

Leave a Comment