Hold onto your hats, sisters! We’re about to delve into the turbulent, transformative, and utterly infuriating history of Second-Wave Feminism. Forget the sanitized version they teach in schools. We’re digging into the muck, the mire, the messy, glorious rebellion that reshaped the world – and still leaves us battling patriarchy’s insidious grip today. Buckle up; this isn’t your grandma’s history lesson. It’s a call to arms, a reminder of how far we’ve come, and how tragically far we still have to go. Prepare for a chronal expedition; this is a timeline you won’t soon forget.

The Pre-Dawn: Post-War Discontent (1940s-1950s)

Let’s dispel the myth of the happy housewife. While Rosie the Riveter traded her welding torch for a vacuum cleaner, the embers of discontent simmered beneath the surface of domestic bliss. Women, having tasted independence and responsibility during the war, found themselves thrust back into prescribed roles of homemakers and mothers. The cultural narrative was suffocating, a constant barrage of messages reinforcing their supposed “natural” place in the home. This period, marked by a societal reflux back to traditional gender roles, laid the foundation for the burgeoning feminist movement. Did we truly believe that our newfound strength would be discarded? Or was the so called ‘woman’s place’ an elaborate cage? The very notion sends shivers down my spine.

The Spark Ignites: Early 1960s – The Personal is Political

Betty Friedan’s *The Feminine Mystique* (1963) detonated like a bomb. Finally, someone articulated “the problem that has no name” – the pervasive dissatisfaction and unfulfilled potential felt by countless women trapped in the gilded cage of suburban domesticity. Friedan’s work became a catalyst, a veritable incunabulum for the second wave. Simultaneously, Simone de Beauvoir’s existentialist analysis in *The Second Sex* (originally published in 1949 but gaining traction in the US) challenged the very construction of womanhood, declaring, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” These words ignited the tinder of frustration, giving women the language to articulate their experiences and the courage to question the status quo. This wasn’t just about equal pay; it was about dismantling the entire edifice of patriarchal oppression. Furthermore, the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement provided a template for social activism, empowering women to organize and demand change. The air crackled with potential.

Radicalization and Diversification (Mid-1960s – Early 1970s)

This era witnessed an explosion of feminist thought and activism, a vibrant tapestry woven from diverse strands. The National Organization for Women (NOW), co-founded by Friedan in 1966, focused on legal and political reforms, advocating for equal opportunities in employment, education, and reproductive rights. However, NOW’s approach was often criticized for being too focused on the concerns of middle-class white women, neglecting the needs of women of color, working-class women, and lesbians. This critique fueled the growth of more radical and intersectional feminist groups. The rise of radical feminism challenged the very foundations of patriarchal society, arguing that male domination was the root of all oppression. Groups like the Redstockings and WITCH (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell) employed provocative tactics and consciousness-raising sessions to expose the systemic nature of sexism. They championed issues like reproductive freedom, rape crisis centers, and domestic violence shelters, addressing the lived realities of women in a way that mainstream organizations often overlooked. Furthermore, Black feminists, led by figures like Audre Lorde and bell hooks, challenged the racism within the feminist movement itself, highlighting the unique experiences of Black women who faced both sexism and racial discrimination. They introduced the concept of intersectionality, recognizing that various forms of oppression – race, class, gender, sexual orientation – are interconnected and cannot be understood in isolation. This period represented a crucial dichotomy: a quest for reform versus a desire for radical change.

Legislative Victories and Backlash (Early 1970s)

The feminist movement achieved significant legislative victories during this period. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibited sex discrimination in any educational program or activity receiving federal funding, opening doors for women in sports and academia. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) began to take sex discrimination complaints more seriously. The Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973 legalized abortion nationwide, a landmark victory for reproductive rights. However, these gains were met with fierce resistance from conservative forces. The anti-feminist backlash began to gain momentum, fueled by religious conservatives and right-wing political groups. Phyllis Schlafly emerged as a prominent opponent of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), arguing that it would destroy traditional family values and harm women. Her organization, Stop ERA, successfully mobilized conservative women and effectively stalled the ratification of the amendment. This was a period of triumph marred by the looming shadow of retrenchment.

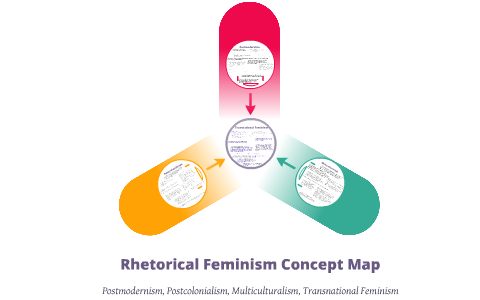

The ERA’s Demise and Shifting Focus (Late 1970s – 1980s)

The failure to ratify the ERA by the 1982 deadline was a major setback for the feminist movement. While proponents blamed conservative opposition and a lack of political will, internal divisions within the movement also contributed to the ERA’s demise. The focus shifted from large-scale legislative reforms to more localized and issue-specific activism. Feminist scholars and activists began to explore new theoretical frameworks, such as postmodern feminism and queer theory, which challenged traditional notions of gender and sexuality. The rise of identity politics led to further fragmentation within the movement, as different groups prioritized their own specific concerns. The emergence of feminist art, literature, and music provided new avenues for expressing feminist ideas and challenging patriarchal norms. This period marked a transition from a unified movement to a more decentralized and diverse landscape, a period of flux and reformulation.

The Reagan Years and the Culture Wars (1980s)

The Reagan administration ushered in a period of conservative backlash against feminism. Funding for social programs that benefited women and minorities was slashed. The anti-abortion movement gained political power, challenging Roe v. Wade and restricting access to reproductive healthcare. The culture wars intensified, with debates over issues like pornography, sexuality, and gender roles dominating the public discourse. Despite these challenges, feminist activism continued, focusing on issues like pay equity, sexual harassment, and violence against women. The Anita Hill case in 1991, in which Hill accused Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment, brought the issue of sexual harassment into the national spotlight and galvanized feminist activists. The Reagan era forced feminists to become more strategic and resilient, a period of fortification against encroaching conservatism.

Third-Wave Stirrings (Early 1990s)

The early 1990s saw the emergence of Third-Wave Feminism, a new generation of activists who challenged the perceived limitations of Second-Wave Feminism. Third-wavers embraced individualism, diversity, and a more nuanced understanding of gender and sexuality. They rejected essentialist notions of womanhood and embraced a more fluid and performative view of gender. Riot Grrrl, a feminist punk rock movement, provided a powerful outlet for young women to express their anger and frustration with sexism. Third-Wave Feminism also utilized new technologies, such as the internet, to organize and mobilize. This was a period of effervescence, a bubbling up of new ideas and perspectives.

Legacy and Lingering Battles

Second-Wave Feminism irrevocably transformed society. It challenged traditional gender roles, expanded women’s rights, and paved the way for greater equality in education, employment, and politics. However, the fight is far from over. Women still face significant challenges, including the gender pay gap, sexual harassment, violence against women, and lack of representation in leadership positions. The anti-feminist backlash continues to be a powerful force, seeking to roll back the gains made by the feminist movement. The struggle for reproductive rights remains a central battleground. The challenges are vast, but the legacy of the second wave inspires us to continue fighting for a more just and equitable world. A world where the concept of “woman’s place” is confined to the dustbin of history. We must continue to agitate, interrogate, and dismantle the structures of power that perpetuate inequality. Only then can we truly claim victory. The spirit of the second wave, in all its messy, contradictory, and ultimately transformative glory, lives on. The fight continues. It’s not just about equality; it’s about liberation, about dismantling the patriarchal structures that bind us all. Now, more than ever, we need to channel the spirit of those fearless feminists who dared to challenge the status quo and demand a better world. Let us march forward, armed with knowledge, passion, and an unwavering commitment to justice. The future is female, and it’s ours to create! The battle for true equality will continue until true liberation is achieved.

Leave a Comment