The so-called “Third Way Feminism,” a term dripping with both promise and potential betrayal, emerged from the ashes of its predecessors, promising a novel route through the labyrinthine landscape of gender politics. But is it truly a new path, or merely a well-trodden, slightly re-paved version of the same old road? It demands rigorous, unblinking scrutiny, lest we find ourselves seduced by its siren song and led astray.

This exploration will dissect Third Wave Feminism’s tenets, critically examining its supposed departure from Second Wave orthodoxies. We will delve into its engagement with intersectionality, its focus on individual empowerment, and its often-uneasy relationship with structural critique. Prepare to have your assumptions challenged. Question everything. Because complacency is the enemy of progress.

I. Genesis of the Third Wave: A Reaction and a Reimagining

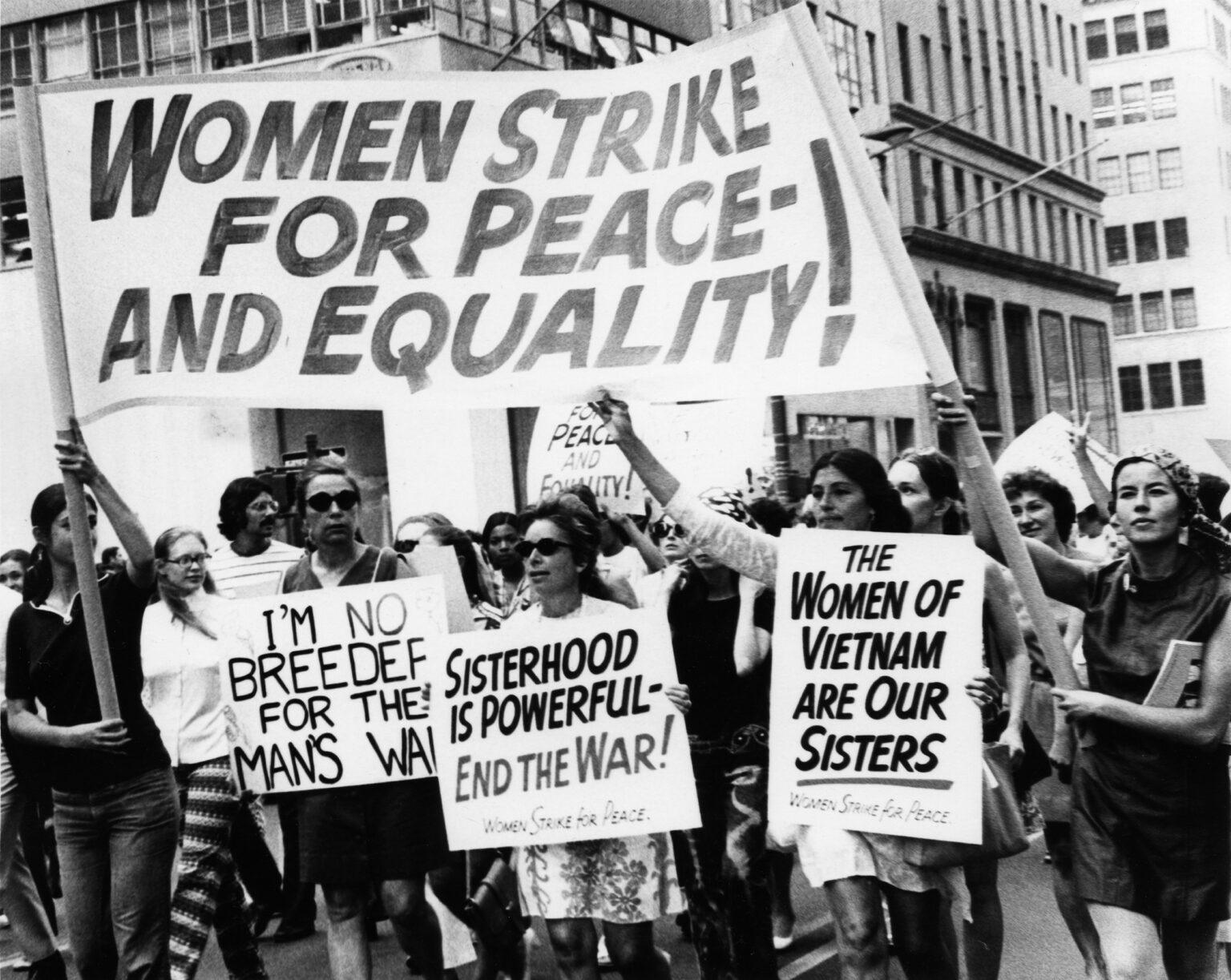

The late 20th century witnessed the birth of this supposedly innovative iteration of feminism. It’s important to understand the context. It arose, ostensibly, as a response to perceived shortcomings and limitations of Second Wave feminism, which, it was argued, often privileged the experiences of white, middle-class, heterosexual women. A valid criticism, certainly. But does the reaction truly address the core issues or simply shift the focus?

Consider this: the Second Wave, with its focus on legal reforms, reproductive rights, and challenging patriarchal institutions, laid the groundwork for many of the freedoms that later generations would take for granted. Was it perfect? Absolutely not. Did it leave voices unheard? Undoubtedly. But to dismiss it entirely is to ignore the monumental battles fought and won. Third Wave Feminism, at least in theory, sought to rectify these oversights, embracing a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of gender, power, and identity.

A. Key Disagreements with Second Wave Feminism

Several core disagreements fueled the emergence of this third iteration of feminism. First and foremost was the perceived essentialism of the Second Wave – the idea that there was a universal “woman” experience. Third Wave feminists rejected this notion, arguing that gender is socially constructed and varies widely based on race, class, sexuality, and other factors. This is a crucial point. We are not a monolithic entity. Our experiences are shaped by the complex interplay of multiple identities.

Secondly, there was a critique of the Second Wave’s focus on victimhood. While acknowledging the reality of gender-based oppression, Third Wave feminists often emphasized individual agency and empowerment. They championed the idea that women could embrace their sexuality, express themselves freely, and challenge patriarchal norms on their own terms. But does this emphasis on individual empowerment overshadow the need for collective action and structural change? That is the question we must constantly ask ourselves.

B. Defining Characteristics: Individuality, Choice, and Intersectional Awareness

Individuality became a defining characteristic. The mantra was “do what you want, be who you want to be.” Choice, often framed as empowering, was paramount. A woman could be a CEO or a stay-at-home mother, a radical activist or a beauty pageant contestant – the choice was hers, and her choice was to be respected. But is all choice truly empowering? Or are some choices constrained by social and economic realities that limit genuine autonomy?

Crucially, intersectional awareness became a cornerstone. Third Wave feminists recognized that gender cannot be understood in isolation from other forms of oppression. They sought to amplify the voices of marginalized women and address the specific challenges they face. This commitment to intersectionality is perhaps the most significant contribution. But it also presents a significant challenge: how to effectively address the complex interplay of multiple oppressions without diluting the focus on gender inequality?

II. Examining the Core Tenets: Empowerment and Individualism Under Scrutiny

The discourse of empowerment, central to Third Wave ideology, warrants careful examination. It’s a seductive word, promising agency and control. But what does it actually mean in practice? Does it translate into meaningful social change, or does it simply serve to mask persistent inequalities? We must be critical. We must be vigilant.

A. The Double-Edged Sword of Empowerment

On one hand, the emphasis on empowerment can be liberating. It encourages women to embrace their strengths, challenge limiting beliefs, and pursue their goals with confidence. It can foster a sense of self-worth and resilience. This is undeniable. Empowerment can be a powerful force for personal growth.

On the other hand, the concept of empowerment can be co-opted and commodified. It can be used to sell products, promote individualistic ideologies, and obscure the systemic barriers that continue to hold women back. Consider the “girlboss” phenomenon, which celebrates individual success while often ignoring the exploitative labor practices that underpin it. Empowerment without systemic change is ultimately insufficient.

B. Individualism vs. Collectivism: A Contentious Divide

This version of feminism often places a strong emphasis on individual achievement. The focus is on breaking the glass ceiling, climbing the corporate ladder, and achieving personal success. This is not inherently wrong. Individual ambition is not a crime. But when individual success becomes the sole measure of progress, the needs of the collective are often overlooked.

The focus on individual choice can also lead to a neglect of systemic issues. If a woman chooses to stay at home and raise children, is she simply exercising her autonomy, or is she also reinforcing traditional gender roles that limit opportunities for other women? These are difficult questions, demanding nuanced and honest answers. We must be willing to confront uncomfortable truths.

III. Intersectionality: A Promise of Inclusivity, a Challenge of Praxis

The embrace of intersectionality is arguably the most significant contribution of this version of feminism. It acknowledges that gender is not experienced in isolation but is shaped by the complex interplay of race, class, sexuality, and other forms of oppression. But acknowledging intersectionality is not enough. It must be translated into concrete action.

A. Beyond Acknowledgment: Translating Theory into Action

The challenge lies in effectively addressing the specific challenges faced by marginalized women. How do we ensure that the voices of women of color, LGBTQ+ women, and disabled women are not only heard but also centered in feminist discourse and activism? How do we create inclusive spaces where all women feel safe, valued, and respected? These are ongoing challenges, requiring constant reflection and adaptation.

Consider the issue of wage inequality. While all women face a gender pay gap, the gap is significantly wider for women of color. Addressing this requires not only challenging gender discrimination but also tackling the systemic racism that perpetuates economic disparities. This demands a multifaceted approach, addressing both individual biases and structural inequalities.

B. The Pitfalls of “Intersectional Washing”

The term “intersectional washing” has emerged to describe the superficial adoption of intersectional language without genuine commitment to dismantling oppressive systems. Companies and organizations may tout their diversity and inclusion initiatives while perpetuating discriminatory practices behind the scenes. This is a cynical manipulation of progressive ideals. We must be vigilant in calling out such hypocrisy.

True intersectionality requires a radical shift in power dynamics. It demands that we challenge our own biases, listen to marginalized voices, and create space for those who have been historically excluded. It is not simply about adding more faces to the table; it is about dismantling the table altogether and building a new one based on principles of equity and justice.

IV. Criticisms and Limitations: Where Does This Ideology Fall Short?

This version of feminism, despite its commendable goals, has faced considerable criticism. Its emphasis on individual empowerment, its often-uncritical embrace of consumer culture, and its tendency to depoliticize gender issues have all been subject to scrutiny. These are valid concerns. They deserve serious consideration.

A. The Depoliticization of Gender Issues

One common criticism is that it has depoliticized gender issues, focusing on individual expression and lifestyle choices rather than systemic change. This shift can lead to a neglect of the political and economic structures that perpetuate gender inequality. If feminism becomes solely about personal empowerment, it risks losing its transformative potential. A shift in focus from systemic issues to individual expression is a common critique.

For example, the focus on “self-care” as a form of feminist activism can be seen as a distraction from more pressing political issues. While self-care is undoubtedly important, it cannot replace collective action and advocacy. We must not allow the focus on individual well-being to overshadow the need for systemic change.

B. Co-optation by Consumer Culture

This version of feminism has been accused of being co-opted by consumer culture. Companies often use feminist messaging to sell products, appealing to women’s desire for empowerment and self-expression. This can lead to a situation where feminism becomes a marketing tool rather than a movement for social change. This is a dangerous trend, as it can dilute the meaning of feminism and undermine its radical potential.

Consider the proliferation of “feminist” merchandise – t-shirts, mugs, and tote bags emblazoned with empowering slogans. While these items may be well-intentioned, they often serve to reinforce consumerism rather than promote meaningful activism. We must be wary of reducing feminism to a commodity. This can have long lasting negative effects. This should concern everyone.

V. The Future of Feminism: Beyond the Third Wave?

The question, then, is where do we go from here? Is there a future beyond the paradigm, one that transcends its limitations and builds upon its strengths? The answer, I believe, lies in embracing a more critical, intersectional, and politically engaged approach to gender justice. This requires a willingness to challenge power structures, amplify marginalized voices, and prioritize collective action over individual achievement.

We must move beyond the binary of individual empowerment and structural critique, recognizing that both are essential for achieving lasting change. We must embrace a vision of feminism that is both transformative and sustainable, one that addresses the root causes of gender inequality and creates a world where all genders can thrive. The future of feminism must center on the global. The future of feminism must be intersectional. The future of feminism must be radical.

Leave a Comment