Honey, are we *really* still doing this? Decades after the so-called “second wave,” are we still dissecting bra-burning myths and dissecting consciousness-raising circles? Or are we ready to acknowledge the triumphs, the fissures, and, yes, the outright failures of a movement that dared to demand more than just a pretty face and a domestic role? This is not just about a timeline; it’s about confronting a legacy. A legacy often romanticized, frequently misunderstood, and perpetually contested.

Consider this your decoder ring to navigate the labyrinthine legacy of second-wave feminism, sans the sugarcoating. We’re diving headfirst into the socio-political maelstrom that birthed it, the key milestones that defined it, the ideological fault lines that threatened to shatter it, and ultimately, the reverberations that continue to shape the feminist discourse of today. Buckle up, buttercups. This ride might be bumpier than you think.

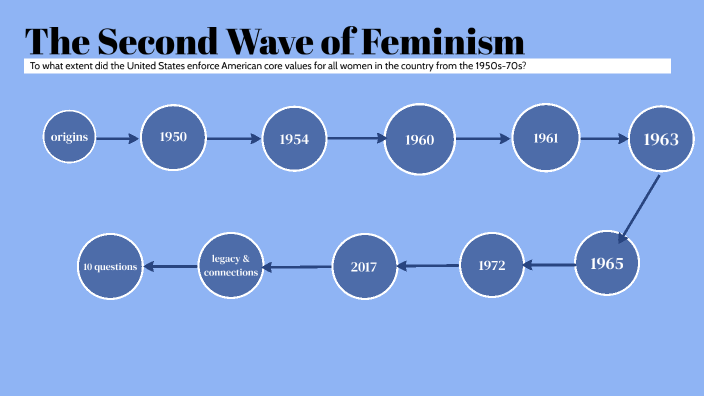

The Crucible of Change: Laying the Groundwork (Pre-1960s)

Let’s not pretend second-wave feminism materialized ex nihilo. It was forged in the crucible of post-war disillusionment, simmering beneath the veneer of suburban bliss. While the boys came home heroes, the Rosie-the-Riveters were expected to hang up their welding torches and resume their “rightful” place in the kitchen. The problem? They’d tasted freedom, independence, and economic autonomy, and they weren’t exactly thrilled about trading it for Tupperware parties and Stepford smiles. This brewing discontent, coupled with the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, created a fertile ground for a new wave of feminist thought.

Key precursors included Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal work, *The Second Sex* (1949), a philosophical juggernaut that dissected the societal construction of womanhood, declaring “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” The ripples of this existentialist earthquake were felt across the globe, challenging the very notion of female essentialism. Furthermore, figures like Margaret Sanger, a pioneer in the fight for reproductive rights, laid the groundwork for the battles to come, even if her eugenicist leanings cast a long and problematic shadow on her legacy.

The Ignition: Early 1960s – Mid 1970s – Defining the Terrain

The publication of Betty Friedan’s *The Feminine Mystique* in 1963 acted as the starter pistol for the second wave. Friedan gave voice to “the problem that has no name,” the pervasive sense of dissatisfaction felt by educated, middle-class housewives trapped in the gilded cage of domesticity. It resonated with a generation of women who felt gaslighted into believing their unhappiness was a personal failing, rather than a systemic issue. This pivotal moment catalyzed the formation of organizations like the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, initially focusing on legal and political equality within the existing system. They pursued legislative reforms like the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), advocating for equal pay, access to education, and an end to sex discrimination in employment.

However, the movement quickly fractured into diverse factions, each with its own priorities and strategies. Radical feminists, disillusioned with the perceived incrementalism of NOW, advocated for a more fundamental restructuring of society. Groups like the Redstockings challenged patriarchal power structures at their roots, focusing on issues like rape, domestic violence, and reproductive freedom. The personal became political as consciousness-raising groups emerged, providing safe spaces for women to share their experiences and analyze the systemic oppression they faced. These gatherings, often derided as mere gripe sessions, were actually powerful engines of political awareness and solidarity.

Crucially, this period also witnessed a burgeoning feminist art movement, challenging the male gaze and reclaiming female representation. Artists like Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro created explicitly feminist artworks that celebrated female experiences and challenged traditional notions of beauty and artistic value. Their work aimed to disrupt the male-dominated art world and create space for female artists and perspectives.

Ideological Fault Lines: Divisions and Debates

The second wave was far from a monolithic entity. Internal divisions based on race, class, sexual orientation, and ideological persuasions threatened to undermine its cohesiveness. White, middle-class feminists were often accused of neglecting the concerns of women of color and working-class women, whose experiences of oppression were compounded by racism and economic inequality. The Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist group formed in 1974, articulated the concept of intersectionality, highlighting the interconnected nature of various forms of oppression and challenging the dominant narrative of white feminism. Their work emphasized the importance of centering the experiences of marginalized women and building solidarity across different identities.

Furthermore, debates raged over issues like sexuality and pornography. Lesbian feminists challenged heteronormativity within the movement, arguing that compulsory heterosexuality was a tool of patriarchal control. The feminist sex wars erupted over the issue of pornography, with some feminists arguing that it was inherently exploitative and harmful to women, while others defended it as a form of sexual expression. These debates exposed deep divisions within the movement and continue to resonate in contemporary feminist discourse.

Mid 1970s – 1980s: Backlash and Consolidation

The gains of the early second wave were met with a fierce backlash in the late 1970s and 1980s. The rise of the New Right and the Moral Majority, spearheaded by figures like Phyllis Schlafly, actively campaigned against the ERA and other feminist initiatives, framing them as a threat to traditional family values. Schlafly’s STOP ERA movement successfully mobilized conservative women and helped to defeat the amendment, a major setback for the feminist movement.

Despite this backlash, second-wave feminism continued to have a profound impact on society. Women made significant gains in education, employment, and politics. Title IX, passed in 1972, prohibited sex discrimination in educational institutions, leading to increased opportunities for women in sports and academia. The women’s health movement challenged the male-dominated medical establishment and advocated for greater control over women’s bodies. The establishment of women’s studies programs in universities across the country provided a space for feminist scholarship and activism.

The Enduring Legacy: Reverberations and Reinterpretations

Second-wave feminism may be a historical artifact, but its echoes reverberate through contemporary feminist discourse. The debates over intersectionality, sexuality, and pornography continue to shape feminist thought and activism. The gains made in legal and political equality have paved the way for further progress, but the fight for true gender equality is far from over. The movement’s focus on issues like reproductive rights, violence against women, and economic justice remains relevant in the 21st century.

Third-wave feminism, emerging in the 1990s, built upon the foundation laid by the second wave, while also challenging its limitations. Third-wave feminists embraced individualism and diversity, rejecting essentialist notions of womanhood. They challenged traditional gender roles and celebrated female agency and empowerment. However, some critics argue that third-wave feminism lost sight of the collective action and political activism that characterized the second wave.

Today, we grapple with fourth-wave feminism, fueled by social media and digital activism. This wave confronts issues like online harassment, rape culture, and the persistent wage gap, wielding hashtags as weapons and mobilizing online communities for change. But even as we celebrate the possibilities of this new era, we must remain critical of its potential pitfalls. Are we truly dismantling systemic oppression, or are we simply curating feminist aesthetics for Instagram likes?

Beyond the Timeline: A Perpetual Provocation

The timeline of second-wave feminism is not a neat, linear progression, but a messy, contested, and ultimately transformative period in history. Its legacy is not a set of answers, but a set of questions. How do we build a feminist movement that is truly inclusive and intersectional? How do we challenge patriarchal power structures in all their forms? How do we create a world where all women can live free from oppression and discrimination? These are the questions that continue to drive the feminist struggle today, and they are questions that demand our constant attention, critical engagement, and unwavering commitment. The timeline is just the beginning. The real work? That’s up to us.

Leave a Comment