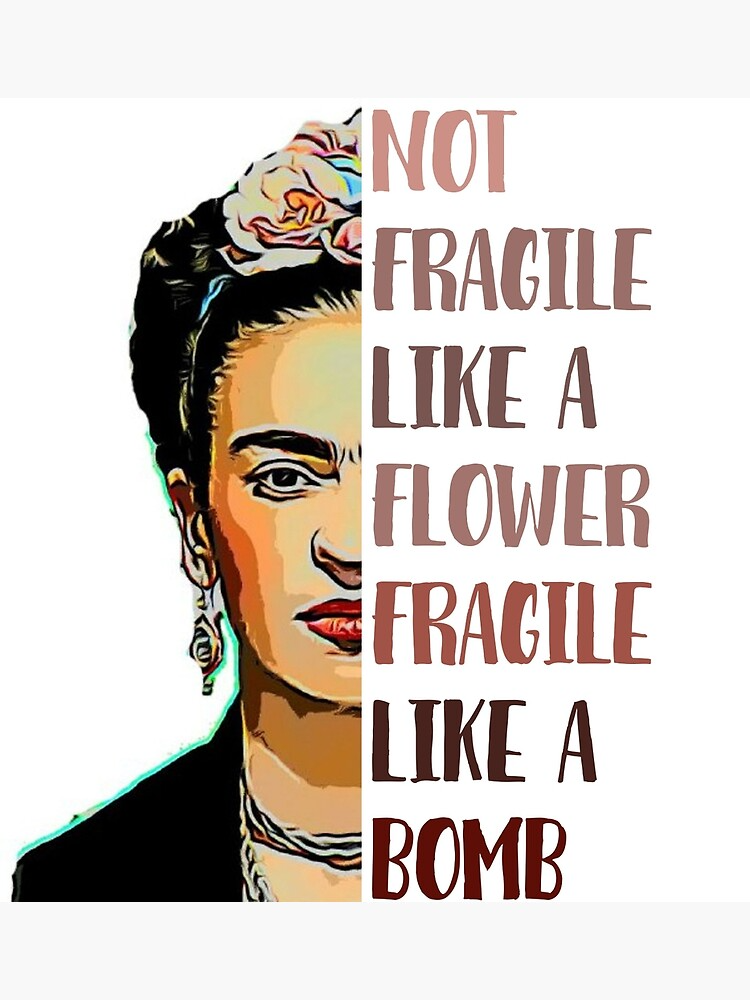

Why Frida? Seriously, amidst a pantheon of historical figures, why is this woman, with her unwavering gaze and defiant unibrow, still plastered on tote bags and dorm room walls? Is it merely the exotic allure, the vaguely subversive aesthetic? Please. It’s something far more visceral, a primal scream resonating across generations of women who have been told to be quiet, to be pretty, to be palatable. Frida Kahlo, my sisters, is a battle cry painted in blood and blossoming rebellion.

The commonly observed fascination with Kahlo often boils down to her “suffering.” Ah, yes, the quaint notion that a woman’s worth is somehow enhanced by her capacity for enduring pain. But to reduce Frida to a martyr of misfortune is to fundamentally misunderstand the ferocious agency at the heart of her art. Her pain wasn’t a weakness; it was the crucible in which her power was forged, the catalyst for a radical act of self-definition in a world that sought to diminish her.

Let us delve, then, into the thorny garden of Frida’s feminism, dissecting the triumvirate of themes that pulse within her oeuvre: pain, power, and the unapologetic articulation of self. This isn’t a mere academic exercise; it’s a reclamation, a re-contextualization, a defiant act of solidarity with a woman who dared to paint her truth onto the canvas of a patriarchal world.

I. The Anatomization of Agony: Painting the Unspeakable

Forget the demure watercolors of flowered landscapes. Frida Kahlo’s canvases are a visceral landscape of the body, ravaged and resurrected. Her chronic pain, a consequence of childhood polio and a devastating bus accident, wasn’t a subject she shied away from; it was the very foundation of her artistic vocabulary.

A. The Broken Column: A Manifesto of Embodied Experience: This self-portrait, perhaps one of her most iconic, depicts Frida with her torso bisected, revealing a crumbling Ionic column in place of her spine. Nails pierce her flesh, a visual litany of her physical torment. But look closer. Her gaze is unwavering, defiant. This isn’t a plea for pity; it’s an assertion of survival, a testament to the enduring strength of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable adversity.

B. Henry Ford Hospital: The Trauma of Reproductive Loss: The stark realism of this painting, depicting Frida bleeding on a hospital bed after a miscarriage, is a brutal counterpoint to the sanitized narratives surrounding female reproduction. It’s a raw, unflinching portrayal of the grief and anguish that often remain unspoken in a society that values women primarily for their childbearing capabilities. This isn’t merely personal pain; it’s a political statement, a challenge to the societal expectations placed upon women’s bodies.

C. Beyond the Physical: The Metaphysics of Suffering: Frida’s pain wasn’t limited to the physical realm. Her tumultuous relationship with Diego Rivera, her infidelity, and her struggles with identity all contributed to a profound sense of emotional anguish. These experiences, too, found their way onto her canvases, transforming personal torment into universal expressions of human vulnerability.

II. Reclaiming Agency: The Power of Self-Representation

In a world that sought to define her through the lens of her suffering, Frida Kahlo seized the narrative. She became the architect of her own image, constructing a powerful persona that defied societal expectations and celebrated her unique identity.

A. The Unibrow as a Badge of Honor: Embracing Imperfection: Frida’s signature unibrow, far from being a flaw to be corrected, became a symbol of her refusal to conform to conventional beauty standards. It was a declaration of authenticity, a rejection of the patriarchal gaze that demanded women erase any trace of “imperfection.” She embraced her “flaws” as integral parts of her identity, transforming them into symbols of strength and individuality.

B. Tehuana Dresses and Indigenous Identity: A Reclamation of Heritage: Frida’s adoption of traditional Tehuana dresses was more than just a fashion statement; it was a political act, a deliberate embrace of her Mexican heritage in a post-colonial world that often denigrated indigenous cultures. She used her clothing as a form of resistance, asserting her cultural identity and challenging the dominant Western aesthetic.

C. Self-Portraits as Acts of Resistance: Subverting the Male Gaze: Frida’s self-portraits weren’t mere exercises in narcissism; they were acts of defiance against the male gaze. She painted herself as she saw herself, flaws and all, refusing to be objectified or idealized for the pleasure of the male viewer. She reclaimed her own image, transforming herself from an object of observation into a powerful subject.

III. The Articulation of Self: Voicing the Unvoiced

Frida Kahlo’s art was a potent vehicle for self-expression, a means of articulating the complexities of her inner world in a society that often silenced women’s voices. She used her canvases as a confessional, a stage, and a weapon, challenging societal norms and paving the way for future generations of female artists.

A. Surrealism and the Subconscious: Exploring the Depths of the Psyche: While Frida rejected the label of “Surrealist,” her work undeniably draws upon the imagery and techniques of the movement. She used surrealist elements to explore the depths of her subconscious, giving voice to the hidden desires, fears, and anxieties that often remained unexpressed in polite society.

B. The Power of Symbolism: Decoding the Language of Pain and Resilience: Frida’s paintings are replete with symbolism, drawing upon Mexican folklore, indigenous mythology, and personal experiences to create a complex and layered visual language. From monkeys and parrots to thorns and hummingbirds, each symbol carries a specific meaning, revealing the intricacies of her emotional landscape.

C. Beyond the Personal: Connecting with the Collective Female Experience: While Frida’s art was deeply personal, it also resonated with the collective experiences of women across cultures and generations. Her struggles with pain, infertility, and identity resonated with countless women who had been silenced, marginalized, and objectified by a patriarchal world. Her art became a catalyst for dialogue, a space for women to connect, share their stories, and find solace in shared experiences.

Frida Kahlo’s feminism, therefore, is not a neatly packaged ideology but a messy, complicated, and ultimately revolutionary act of self-definition. It’s a feminism born from pain, fueled by resilience, and expressed through the unapologetic articulation of self. She didn’t just paint her life; she painted a roadmap for survival, a testament to the power of self-expression in a world that seeks to silence and diminish the voices of women. Her legacy is not one of victimhood but of defiant agency, a powerful reminder that even in the face of unimaginable adversity, we have the power to reclaim our bodies, our identities, and our voices. So, the next time you see Frida’s image staring back at you, don’t just admire her aesthetic; recognize the fire that burns within, the fierce spirit of a woman who dared to paint her truth onto the canvas of a patriarchal world, and in doing so, ignited a revolution.

Leave a Comment