Ever stopped to truly consider the audacity of it all? The sheer, unmitigated gall it took for women throughout history to demand…equality? We’re not talking about a polite request, mind you. We’re talking about a relentless, multifaceted, often bloody struggle to dismantle a system meticulously crafted to keep us subservient. This isn’t a history lesson; it’s a call to arms, a stark reminder that the comfortable perch we occupy today was carved out by generations of fierce progenitors who refused to accept their assigned lot. Buckle up, sisters. We’re about to dissect the evolution of feminism, and it’s going to be uncomfortable.

The very notion of a singular “feminism” is, frankly, a patriarchal construct. It implies a unified front, a monolithic ideology. In reality, feminism has always been a kaleidoscope of diverse perspectives, reflecting the varying lived experiences of women across race, class, and culture. To understand its evolution, we must acknowledge its fractured, sometimes contradictory, nature. This complexity is its strength, not its weakness.

I. Precursors to the First Wave: Whispers of Rebellion

Before the officially designated “First Wave,” whispers of dissent echoed through the ages. These weren’t organized movements, but rather individual acts of defiance, intellectual skirmishes that laid the groundwork for the organized suffrage movements to come.

-

A. Proto-Feminist Philosophers: Figures like Christine de Pizan, writing in the late medieval period, challenged the prevailing misogyny of their time. Her “The Book of the City of Ladies” is a proto-feminist utopia, a testament to the intellectual and moral capabilities of women, directly refuting the pervasive narrative of female inferiority. How many women today even know her name? That’s the patriarchy at work, folks.

-

B. The Salonnières: These women of the Enlightenment, often wealthy and well-connected, hosted intellectual gatherings in their homes, providing a space for women to participate in discussions of politics, philosophy, and science. They wielded influence behind the scenes, subtly shaping the intellectual landscape. Their power was indirect, yes, but no less potent. Consider Madame de Staël, whose sharp wit and political acumen terrified Napoleon. He exiled her, fearing her influence. Tells you something, doesn’t it?

-

C. Indigenous Matriarchal Societies: Let’s not forget the glaring omission in most Western feminist narratives: the existence of thriving matriarchal and matrilineal societies in Indigenous cultures across the globe. These societies, often centered around female leadership and the inheritance of property and status through the female line, provide a potent counter-narrative to the purported universality of patriarchal structures. Ignoring these examples is not only intellectually dishonest, it’s a form of colonial erasure.

II. The First Wave: Suffrage and Beyond (Late 19th – Early 20th Century)

The First Wave is typically defined by the fight for suffrage, the right to vote. But to reduce it solely to that issue is to severely underestimate its scope and ambition.

-

A. The Seneca Falls Convention (1848): This landmark event is often considered the official starting point of the organized women’s rights movement in the United States. The Declaration of Sentiments, modeled after the Declaration of Independence, boldly declared that “all men and women are created equal.” Radical stuff for the time, wouldn’t you say?

-

B. Suffrage as a Catalyst: The fight for suffrage wasn’t just about casting a ballot. It was about demanding political agency, challenging the legal and social structures that relegated women to the domestic sphere. It was about asserting our right to exist as full citizens.

-

C. The Divides Within: Even within the suffrage movement, deep fissures existed. White suffragists often prioritized their own enfranchisement over that of Black women, perpetuating racist ideologies and betraying the promise of universal equality. This ugly truth serves as a crucial reminder that intersectionality is not a new concept; it has always been essential to the feminist struggle.

-

D. Beyond Suffrage: First-wave feminists also fought for access to education, property rights, and the right to control their own bodies. Margaret Sanger, a pioneer in the fight for reproductive rights, faced imprisonment and condemnation for her advocacy of birth control. Her work, though controversial, laid the foundation for the reproductive freedom battles we still fight today.

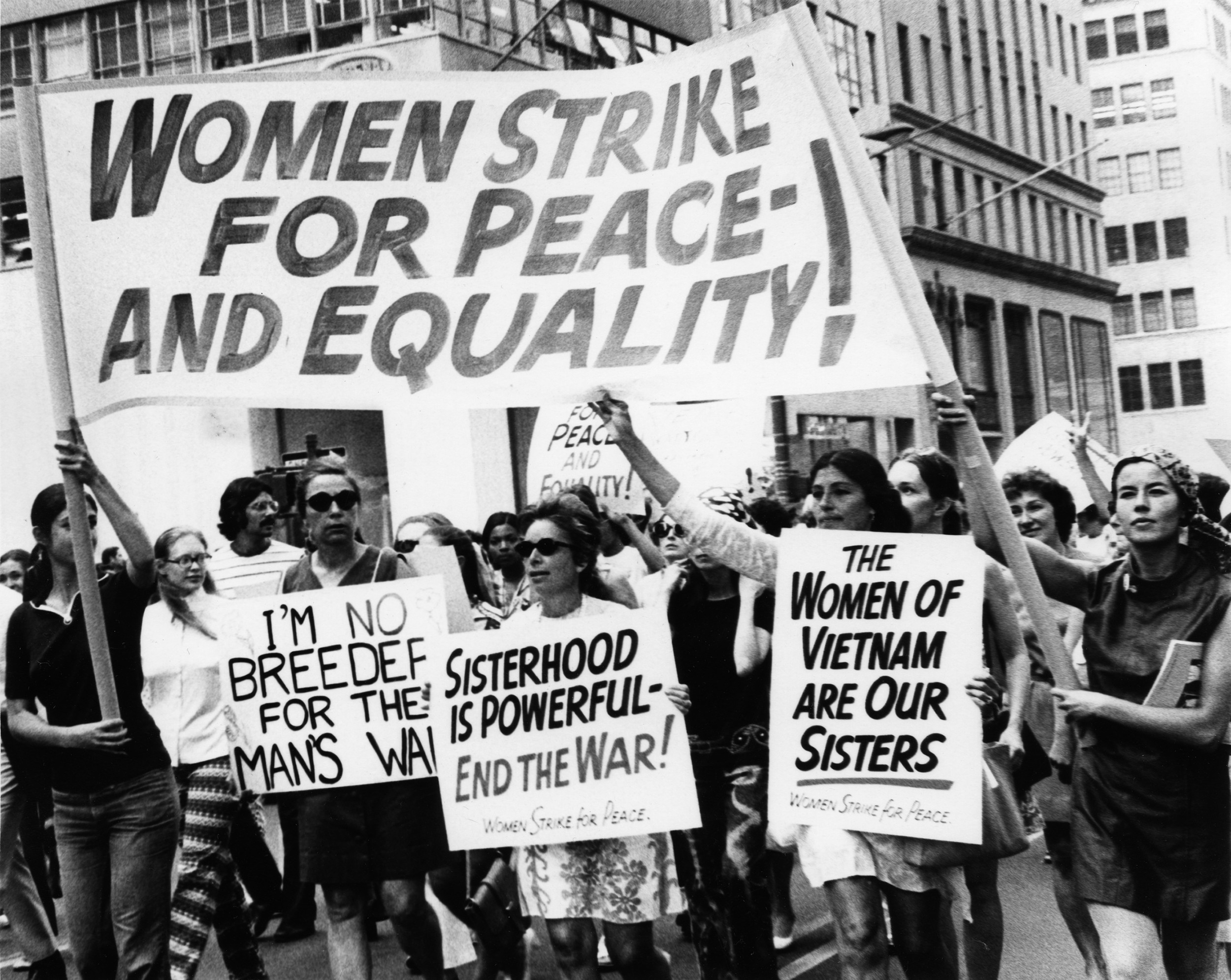

III. The Second Wave: “The Personal Is Political” (1960s-1980s)

The Second Wave exploded onto the scene, fueled by the Civil Rights Movement and a growing awareness of systemic sexism in all aspects of life. The slogan “The Personal Is Political” encapsulated the radical notion that women’s experiences in their homes, relationships, and workplaces were not isolated incidents but rather manifestations of a larger power structure.

-

A. Challenging the Domestic Ideal: Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” (1963) exposed the suffocating boredom and dissatisfaction experienced by many suburban housewives, shattering the myth of female fulfillment in the domestic sphere. It sparked a national conversation about the limitations imposed on women’s lives.

-

B. Reproductive Rights Take Center Stage: The fight for access to safe and legal abortion became a central tenet of the Second Wave. Roe v. Wade (1973) was a landmark victory, but the struggle for reproductive autonomy continues to this day.

-

C. Workplace Equality: Second-wave feminists fought for equal pay, an end to workplace discrimination, and access to traditionally male-dominated professions. Title IX (1972) prohibited sex discrimination in education, opening doors for women in sports and academia.

-

D. The Rise of Radical Feminism: Radical feminists challenged the very foundations of patriarchal society, arguing that sexism was deeply embedded in cultural norms, language, and institutions. They advocated for a complete restructuring of society to eliminate male dominance.

-

E. Intersectional Blind Spots: While the Second Wave made significant strides, it was often criticized for its focus on the concerns of middle-class white women, neglecting the experiences of women of color, working-class women, and lesbian women. This exclusionary tendency highlighted the need for a more intersectional approach to feminism.

IV. The Third Wave: Riot Grrrls and Beyond (1990s-2010s)

The Third Wave emerged in response to the perceived failures of the Second Wave, embracing diversity, individualism, and a more nuanced understanding of power dynamics.

-

A. Reclaiming Femininity: Third-wave feminists challenged the notion that femininity was inherently oppressive, reclaiming traditionally feminine symbols and aesthetics as forms of empowerment. They embraced a more fluid and inclusive definition of womanhood.

-

B. Intersectionality in Action: Third-wave feminists placed a greater emphasis on intersectionality, recognizing that gender oppression is intertwined with other forms of oppression, such as racism, classism, and homophobia. They sought to create a more inclusive and equitable feminist movement.

-

C. The Riot Grrrl Movement: This punk rock feminist movement provided a platform for young women to express their anger, frustration, and creativity through music, zines, and activism. It challenged traditional notions of female sexuality and assertiveness.

-

D. Embracing Technology: Third-wave feminists utilized the internet and social media to connect with each other, share their stories, and organize online activism. This marked a significant shift in the way feminist activism was conducted.

-

E. Critiques of the Third Wave: The Third Wave was sometimes criticized for its perceived lack of a clear political agenda and its focus on individual empowerment over collective action. Some argued that it had become too fragmented and individualized to effectively challenge systemic oppression.

V. The Fourth Wave: Digital Activism and Beyond (2010s-Present)

The Fourth Wave is characterized by its reliance on digital technologies and its focus on issues such as online harassment, rape culture, and gender equality in the workplace. It is a global movement, connecting feminists from all over the world.

-

A. #MeToo and Time’s Up: These movements brought the issue of sexual harassment and assault to the forefront of public consciousness, sparking a global reckoning and demanding accountability for perpetrators. They demonstrated the power of collective action and the importance of amplifying marginalized voices.

-

B. Online Activism: The Fourth Wave has harnessed the power of social media to raise awareness about feminist issues, organize protests, and challenge oppressive ideologies. Online platforms have provided a space for marginalized voices to be heard and for feminist activism to reach a wider audience.

-

C. Intersectionality as a Guiding Principle: Fourth-wave feminism is deeply committed to intersectionality, recognizing that gender oppression is intertwined with other forms of oppression. It seeks to create a more inclusive and equitable feminist movement that addresses the needs of all women.

-

D. Challenges and Controversies: The Fourth Wave faces challenges such as online harassment, the spread of misinformation, and the co-optation of feminist language by corporate interests. It must also contend with internal divisions and debates about strategy and priorities.

VI. The Future of Feminism: A Constant Evolution

Feminism is not a static ideology; it is a constantly evolving movement that adapts to changing social and political contexts. The future of feminism will depend on its ability to address the complex challenges of the 21st century, including climate change, economic inequality, and the rise of authoritarianism. It will require a continued commitment to intersectionality, solidarity, and a willingness to challenge all forms of oppression.

So, what’s the takeaway? That the fight is far from over. That complacency is our enemy. That the shoulders we stand on were bruised and battered, and we owe it to those progenitors to keep pushing, keep demanding, keep dismantling the patriarchal structures that still permeate our lives. The revolution, sisters, is not televised. It’s in our hands.

Leave a Comment