Let’s be honest. The word “feminism” itself. It’s a loaded term. Conjures up images, doesn’t it? Images carefully crafted, often distorted, sometimes outright malicious. But strip away the layers of vitriol and manufactured outrage, and what are we left with? A pursuit of equality. A recognition of systemic imbalances. And a burning desire for a more just world. This isn’t some fringe ideology. It’s the bedrock of a civilized society. Or at least, it should be.

Sociology, the supposed objective observer of human behavior, often tiptoes around feminism, treating it like a spicy dish that might upset the establishment’s bland palate. We need to stop with the equivocating. Feminism isn’t just an approach in sociology; it’s a vital lens through which to examine the entire damn thing. And that, my friends, is where things get interesting.

I. Deconstructing the Dichotomies: Beyond the Binary Gaze

The traditional sociological gaze has, for far too long, perpetuated a binary view of the world. Male versus female. Public versus private. Rational versus emotional. These are not simply neutral observations. They are socially constructed hierarchies, designed to maintain power structures. Feminism challenges this very foundation, demanding a more nuanced understanding of human experience.

A. The Patriarchy Unmasked: Unveiling Systemic Oppression

We’re not talking about individual men being “bad.” This isn’t about demonizing a gender. The patriarchy, as a sociological construct, is a system of power relations where male dominance is normalized and institutionalized. It permeates our laws, our media, our very language. It’s the air we breathe, and recognizing its insidious influence is the first step to dismantling it. For example, the wage gap isn’t a simple market anomaly. It’s a direct result of the devaluation of women’s labor, a legacy of patriarchal assumptions about their roles in society. Similarly, the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions isn’t a matter of individual choice; it’s a consequence of systemic barriers that subtly and overtly discourage their advancement. Think of the “glass ceiling,” the subtle but impenetrable barrier that keeps women from reaching the highest echelons of power. Then there’s the “sticky floor,” trapping women in lower-paying, less prestigious jobs.

B. Intersectionality: A Kaleidoscope of Oppressions

Here’s where things get even more complex, and rightfully so. Feminism isn’t a monolithic movement. It recognizes that gender is just one facet of identity, intersecting with race, class, sexuality, ability, and countless other factors. These intersections create unique experiences of oppression that cannot be understood through a single lens. A Black woman, for instance, faces challenges that are distinct from those faced by a white woman or a Black man. Her experience is shaped by the intersection of racism and sexism, a double bind that demands a more nuanced analysis. Intersectionality compels us to move beyond simplistic generalizations and to acknowledge the diverse realities of women’s lives.

C. Challenging the “Objective” Observer: Embracing Situated Knowledge

Sociology has long claimed objectivity, but let’s be real. Knowledge is never neutral. It’s always situated, shaped by the researcher’s own experiences, biases, and social location. Feminism challenges this pretense of objectivity, arguing that acknowledging our situatedness is essential for producing more rigorous and relevant research. A feminist sociologist doesn’t pretend to be a detached observer. They acknowledge their own perspectives and biases, and they actively seek to understand the experiences of those they study from their own perspectives. This involves employing methodologies that empower participants, such as participatory action research, where the research is driven by the needs and priorities of the community being studied.

II. Rewriting the Narrative: From Victimhood to Agency

Too often, women are portrayed as passive victims of patriarchal forces. While acknowledging the reality of oppression is crucial, feminism also emphasizes women’s agency, their resilience, and their capacity to resist and transform their circumstances.

A. Reclaiming the Body: Rejecting Objectification and Embracing Embodiment

The female body has been relentlessly objectified, commodified, and controlled throughout history. Feminism challenges this objectification, arguing that women have the right to control their own bodies and to define their own identities. This includes challenging unrealistic beauty standards, advocating for reproductive rights, and combating sexual violence. Embodiment emphasizes the lived experience of being in a body, rejecting the separation of mind and body that has long been a hallmark of Western thought. It calls for a celebration of the diversity of female bodies and a rejection of the pressure to conform to narrow and oppressive ideals.

B. Amplifying Voices: Centering Marginalized Narratives

Traditional sociology has often silenced or marginalized the voices of women, particularly women of color, queer women, and women with disabilities. Feminism seeks to rectify this by centering the experiences and perspectives of these marginalized groups. This involves actively seeking out their stories, amplifying their voices, and challenging dominant narratives that erase or distort their realities. Oral history, for example, can be a powerful tool for uncovering hidden histories and giving voice to those who have been historically silenced. By centering marginalized narratives, we can gain a more complete and accurate understanding of the world.

C. Resistance and Transformation: Collective Action and Social Change

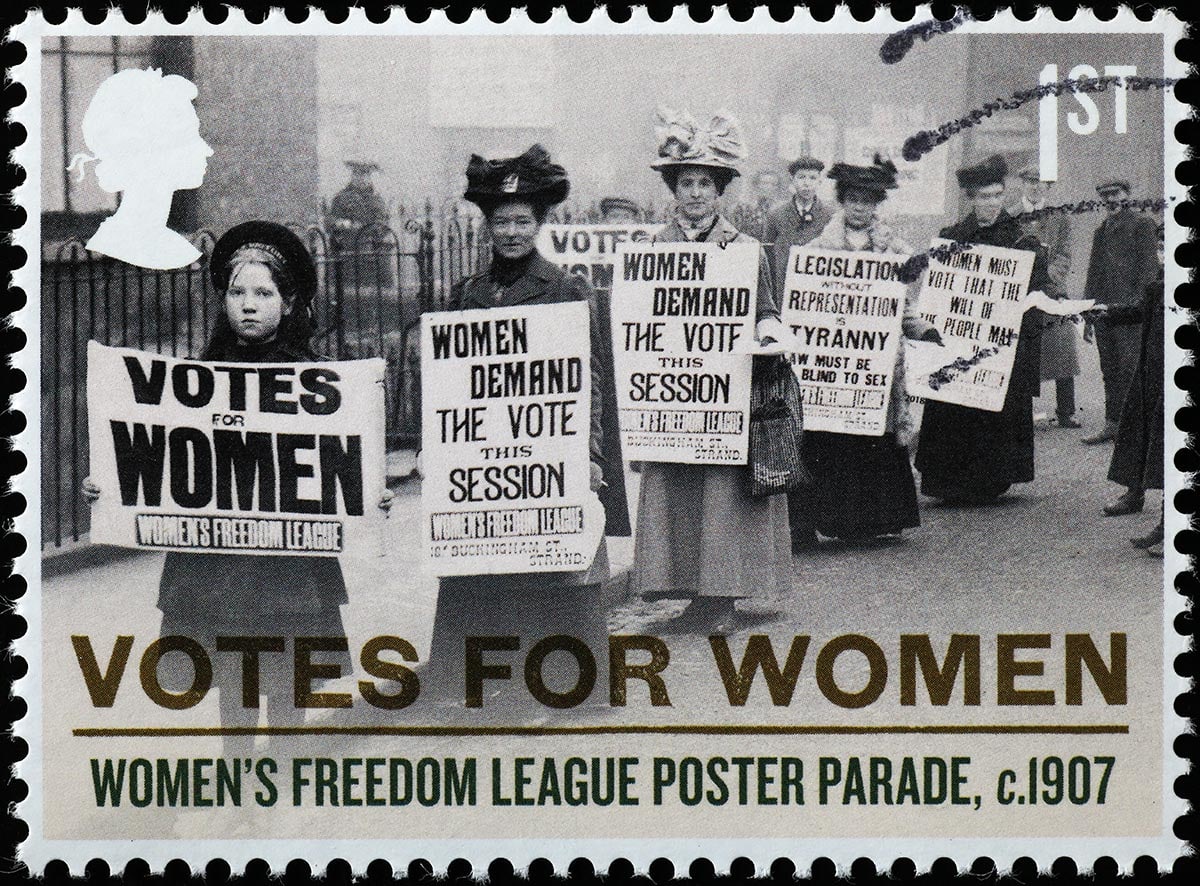

Feminism is not just an academic exercise; it’s a call to action. It recognizes that social change requires collective action, from grassroots organizing to political activism. Throughout history, women have fought tirelessly for their rights, challenging discriminatory laws, organizing labor movements, and advocating for peace. These struggles are not just historical footnotes; they are ongoing and essential for creating a more just world. Consider the #MeToo movement, a powerful example of collective action that has brought widespread attention to the issue of sexual harassment and assault. By sharing their stories and holding perpetrators accountable, women are challenging the culture of silence and demanding systemic change.

III. Reimagining the Future: Towards a Feminist Utopia?

What would a truly feminist society look like? It’s not about simply reversing the power dynamics, replacing male dominance with female dominance. It’s about creating a society where all individuals, regardless of gender, have the opportunity to thrive and reach their full potential.

A. Challenging Gender Roles: Beyond the Confines of Social Scripts

Gender roles are socially constructed expectations about how men and women should behave. They limit our choices, stifle our creativity, and perpetuate inequality. A feminist society would challenge these rigid roles, allowing individuals to express themselves authentically, regardless of their gender. This involves dismantling stereotypes, promoting gender-neutral education, and creating a culture that values diversity and individuality. Consider the impact of gendered toys on children’s development. Toys marketed to girls often emphasize nurturing and domestic skills, while toys marketed to boys often emphasize aggression and competition. These subtle cues can shape children’s perceptions of themselves and their potential, limiting their opportunities later in life.

B. Redefining Power: Moving Beyond Domination and Control

Traditional conceptions of power are often based on domination and control. A feminist perspective challenges this, arguing that power can also be collaborative, empowering, and transformative. This involves creating democratic decision-making processes, fostering empathy and compassion, and promoting social justice. Empowerment is about enabling individuals to take control of their own lives and to participate fully in society. It involves providing access to education, resources, and opportunities, and creating a supportive environment where individuals can thrive.

C. Cultivating Care: Prioritizing Empathy and Social Justice

A feminist society would prioritize care, both for individuals and for the planet. This involves valuing unpaid labor, such as childcare and elder care, and creating policies that support families and communities. It also involves addressing environmental issues, recognizing that environmental degradation disproportionately affects marginalized communities. A care ethic emphasizes the importance of relationships, responsibility, and responsiveness to the needs of others. It challenges the individualistic and competitive values that often dominate Western societies, promoting a more compassionate and sustainable way of living.

Feminism in sociology is not merely a subfield. It’s a radical reimagining of the discipline itself. It’s a call to question everything, to challenge assumptions, and to strive for a more just and equitable world. It’s not about achieving some utopian ideal, but about embarking on a journey of continuous learning, growth, and transformation. So, let’s embrace the challenge. Let’s dismantle the structures of oppression. Let’s build a better future, together.

Leave a Comment