For centuries, the art world has been a gilded cage, meticulously crafted by and for men. Think about it: the celebrated masters, the historical narratives, the very definition of “genius” – all overwhelmingly male. But what happens when the silenced voices, the stifled perspectives, the raw, untamed power of women explodes onto the scene? What happens when art becomes a weapon, a catalyst, a revolutionary act of defiance? That, my friends, is where the story of art and feminism truly begins. We’re talking about a seismic shift, a tectonic upheaval that continues to reshape the artistic landscape, demanding to be seen, to be heard, and to be reckoned with. Buckle up, because we’re about to dismantle some deeply ingrained biases and unearth the radical beauty of feminist art.

The Patriarchy’s Canvas: A Brief History of Exclusion

Let’s not pretend that the artistic playing field was ever level. The historical marginalization of women in art is not some abstract concept; it’s a concrete reality etched into every museum wall, every art history textbook. We’re not just talking about a lack of representation; we’re talking about active suppression. Formal art education, access to materials, patronage – all systematically denied to women for centuries. Need proof? Consider the Old Masters. How many women grace those hallowed halls? A handful, maybe, often relegated to the role of muse or model, never the architect of their own creative destiny. This wasn’t just unfortunate; it was intentional. The patriarchy meticulously curated its artistic narrative, ensuring its dominance remained unchallenged. But silence, as they say, can be deafening.

Consider, for instance, the limitations placed upon female artists regarding subject matter. While men were free to explore grand historical narratives, religious themes, and the burgeoning genre of landscape painting, women were often confined to domestic scenes, portraits, and still lifes – deemed “appropriate” for their supposedly delicate sensibilities. This wasn’t merely a matter of preference; it was a deliberate constriction of their artistic horizons. Their perspectives were deemed too trivial, their experiences too mundane to warrant serious artistic consideration. It was a form of artistic emasculation, designed to keep them firmly in their place. And then consider the lack of mentorship opportunities. Male artists often benefited from apprenticeships, workshops, and the informal networks of the art world, providing crucial opportunities for learning, collaboration, and exposure. Women, on the other hand, were largely excluded from these circles, forced to navigate the treacherous waters of the art world alone, without the support and guidance readily available to their male counterparts.

The First Stirrings: Challenging the Canon

Even amidst this oppressive climate, sparks of rebellion began to flicker. Artists like Artemisia Gentileschi, with her visceral portrayals of female strength and resilience, dared to challenge the prevailing aesthetic norms. She wasn’t depicting passive, decorative women; she was showing them as powerful agents, capable of violence, revenge, and self-determination. Gentileschi wasn’t just painting; she was subverting the entire patriarchal narrative. These early pioneers, often working in isolation, laid the groundwork for the feminist art movement to come. They demonstrated that women could not only create art of equal merit to men but that their perspectives could offer a unique and invaluable contribution to the artistic discourse.

Other names, though less celebrated, echoed similar themes. Sofonisba Anguissola, a Renaissance painter who gained recognition for her portraits, subtly challenged the objectification of women by depicting them with intelligence and agency. Rosa Bonheur, a 19th-century animal painter, defied societal expectations by pursuing a traditionally masculine subject matter and achieving international acclaim. These women, each in their own way, pushed against the boundaries of what was considered acceptable for female artists, paving the way for future generations to break down those barriers altogether. Their courage and determination served as an inspiration, a testament to the enduring power of female creativity in the face of adversity.

The Rise of Feminist Art: A Revolution in Color and Form

The second-wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s provided fertile ground for the explosion of feminist art. This wasn’t just about adding a few more women to museum collections; it was about fundamentally questioning the very foundations of the art world, its power structures, its ingrained biases. Feminist artists began to reclaim their bodies, their experiences, their voices, using art as a tool for consciousness-raising, political activism, and self-expression. Think of Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” a monumental installation celebrating the contributions of women throughout history, a powerful rebuke to the male-dominated narratives that had long dominated the artistic landscape. This was more than just an artwork; it was a declaration of independence, a reclaiming of female history, and a celebration of the power of female solidarity.

The Guerrilla Girls, with their witty and provocative posters, exposed the shocking underrepresentation of women and artists of color in museums. Their anonymity allowed them to speak truth to power without fear of reprisal, their message resonating deeply with a generation hungry for change. They used humor and irony as weapons, dismantling the self-seriousness of the art world and exposing its deep-seated inequalities. These artists weren’t just creating art; they were creating a movement. They were challenging the status quo, demanding accountability, and forcing the art world to confront its own complicity in perpetuating patriarchal structures.

Deconstructing the Male Gaze: Reclaiming the Female Body

A central tenet of feminist art is the deconstruction of the “male gaze,” the idea that art has historically been created from a masculine, heterosexual perspective, objectifying and sexualizing the female body for male consumption. Feminist artists challenged this dominant perspective, creating art that depicted women as subjects, not objects, reclaiming their bodies and their sexuality on their own terms. Artists like Carolee Schneemann, with her performance pieces exploring female sexuality and the body as a site of artistic expression, pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in art, challenging the viewer to confront their own preconceptions about the female form. Schneemann’s work wasn’t always comfortable, but it was always provocative, forcing viewers to confront their own internalized biases and assumptions about the female body.

Hannah Wilke, another pioneering feminist artist, used her own body as a canvas, exploring themes of beauty, aging, and mortality. Her work challenged the societal pressures on women to conform to impossible beauty standards, offering a powerful counter-narrative to the images of idealized femininity that saturated popular culture. Wilke’s art was deeply personal, often raw and vulnerable, but it resonated with countless women who felt similarly alienated and objectified. These artists weren’t just making art; they were engaging in a form of radical self-expression, reclaiming their bodies from the male gaze and asserting their right to define themselves on their own terms.

Beyond the Binary: Intersectional Feminism and Art

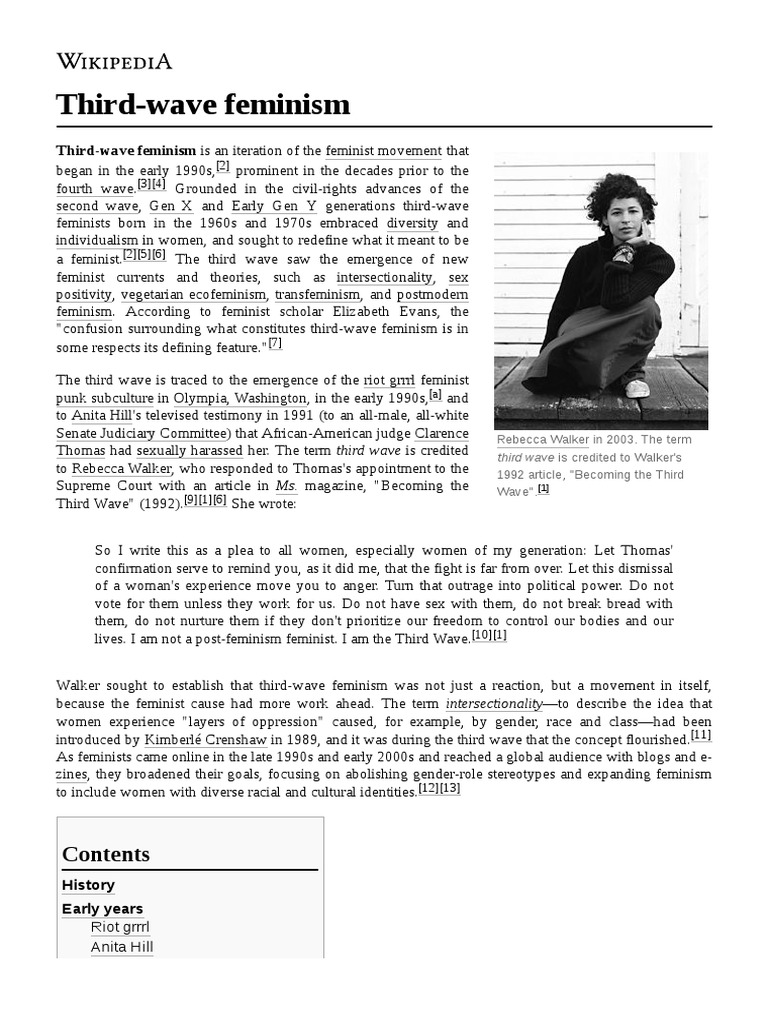

As the feminist movement evolved, so too did feminist art. It became increasingly clear that the experiences of white, middle-class women were not universal. Intersectional feminism recognized the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, creating overlapping systems of discrimination or disadvantage. This led to a more nuanced and inclusive approach to feminist art, exploring the diverse experiences of women from different backgrounds and challenging the erasure of marginalized voices. Artists like Faith Ringgold, with her story quilts depicting African American history and culture, brought a new perspective to the feminist art movement, highlighting the unique challenges faced by black women in a society shaped by both racism and sexism. Ringgold’s work wasn’t just beautiful; it was a powerful act of historical reclamation, giving voice to stories that had long been silenced or ignored.

Guadalupe Rodriguez, with her vibrant and politically charged murals, addresses issues of immigration, labor, and social justice, giving voice to the struggles of Latinx communities. Her art serves as a powerful reminder that feminism must be inclusive of all women, regardless of their race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. These artists are expanding the definition of feminist art, recognizing that the fight for gender equality is inextricably linked to the fight for racial justice, economic justice, and social justice.

The Digital Age: Feminism and Art in the 21st Century

The internet has revolutionized the art world, providing new platforms for feminist artists to connect, collaborate, and share their work. Social media has become a powerful tool for feminist activism, allowing artists to bypass traditional gatekeepers and reach a global audience. Online galleries and digital art platforms have created new opportunities for women artists to showcase their work and gain recognition. The digital age has democratized the art world, giving voice to marginalized communities and challenging the traditional power structures that have long dominated the artistic landscape.

Artists are using digital media to create immersive installations, interactive artworks, and virtual reality experiences that explore feminist themes in new and innovative ways. They are using technology to challenge traditional notions of art and challenge viewers in a radical, immediate sense. It serves as an art form that is accessible to a wider audience and fosters a sense of community and shared experience. The internet has not only changed the way art is created and consumed; it has also empowered a new generation of feminist artists to challenge the status quo and advocate for social change.

The Unfinished Revolution: The Future of Art and Feminism

The struggle for gender equality in the art world is far from over. Despite the progress that has been made, women artists continue to face discrimination, underrepresentation, and unequal pay. Museums and galleries remain overwhelmingly dominated by male artists, and the art market continues to undervalue the work of women. The fight for true equality requires ongoing vigilance, activism, and a commitment to challenging the systemic biases that continue to plague the art world.

The future of art and feminism lies in the hands of the next generation of artists, curators, and art historians who are committed to creating a more inclusive and equitable art world. This requires a willingness to challenge the status quo, to amplify marginalized voices, and to create new opportunities for women artists to thrive. It also requires a critical examination of the ways in which art history has been constructed, recognizing the contributions of women artists who have been overlooked or ignored. By embracing diversity, celebrating female creativity, and challenging the patriarchal structures that continue to shape the art world, we can create a future where all artists have the opportunity to reach their full potential.

The canvas is still being painted, the story still being written. The feminist art movement is not a relic of the past; it is a living, breathing force that continues to challenge, provoke, and inspire. It is a reminder that art has the power to change the world, one brushstroke at a time. Don’t just observe; engage. Question. Disrupt. Create. The revolution is waiting for you.

Leave a Comment