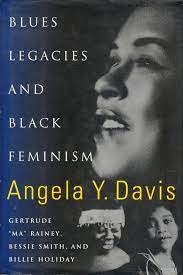

Let’s talk about Angela Davis. Not the icon plastered on dorm room posters, but the intellectual juggernaut who dared to excavate the radical potential buried within the blues. Forget your watered-down, feel-good narratives of empowerment. We’re diving headfirst into “Blues Legacies and Black Feminism,” a text that’s less a book and more a sociopolitical Molotov cocktail. Prepare to have your assumptions about race, gender, and musical expression thoroughly incinerated.

This isn’t just about understanding the blues. This is about understanding how Black women, relegated to the margins of society, crafted a language of resistance, resilience, and raw, unapologetic desire through song. It’s about recognizing the blues as a sophisticated theoretical framework, a praxis of liberation forged in the crucible of oppression. Ready to challenge the status quo? Let’s unravel this intellectual tapestry, thread by subversive thread.

I. The Blues as a Counter-Narrative: Dismantling the Mythology of Southern Womanhood

Davis doesn’t just analyze the music; she deconstructs the entire ideological scaffolding upon which the subjugation of Black women was built. Think about the romanticized image of the Southern belle, that vapid, porcelain doll caricature of femininity. Now, contrast that with the blues woman: Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, women who sang about hard liquor, harder love, and the brutal realities of surviving in a world that actively sought to destroy them. See the chasm? That’s where the revolution begins.

The blues became a sanctuary, a space where Black women could articulate experiences that were systematically erased from the dominant discourse. They sang about economic exploitation, sexual violence, and the psychological toll of living under constant surveillance. These weren’t just personal grievances; they were indictments of a system designed to crush their spirits. In essence, the blues was a collective scream, a defiant assertion of existence in the face of annihilation.

Davis brilliantly argues that these blues women weren’t just passive victims. They were active agents in their own liberation, using their music to challenge societal norms and create a sense of solidarity within their communities. Their songs were blueprints for survival, offering strategies for navigating a hostile world and maintaining a sense of self-worth in the face of relentless degradation. The sonic landscape became a battleground, and these women were armed with nothing but their voices and their unwavering will to resist.

II. The Erotics of Resistance: Reclaiming Female Desire and Agency

Buckle up. We’re about to confront a topic that makes some people squirm: sexuality. Davis fearlessly explores the ways in which the blues allowed Black women to reclaim their bodies and their desires from the clutches of white supremacist patriarchy. This wasn’t about conforming to bourgeois notions of respectability; it was about asserting the right to pleasure, to agency, to define one’s own sexuality on one’s own terms.

Consider the bold, often explicit lyrics of blues singers like Bessie Smith. She sang about lust, about infidelity, about the complexities of female desire with a candor that was shocking for her time (and, let’s be honest, still resonates with a transgressive power today). This wasn’t just about sex; it was about challenging the Victorian morality that sought to confine women to the roles of wife and mother. It was about declaring that Black women were not just vessels for reproduction; they were sentient beings with their own needs and desires.

The concept of “erotics of resistance,” while not explicitly coined by Davis in this work, perfectly encapsulates this aspect of the blues. It’s about using pleasure as a weapon, about reclaiming the body as a site of power, about defying the attempts to control and regulate female sexuality. It’s a radical act of self-definition, a refusal to be silenced or shamed. The blues became a space where Black women could explore their desires without apology, without fear, and without the constraints of societal expectations.

III. The Blues as a Balm: Exploring Themes of Loss, Loneliness, and Resilience

While the blues undoubtedly served as a vehicle for resistance and sexual liberation, it was also a space for processing trauma and grief. The Great Migration, the constant threat of violence, the economic hardship, the systemic racism – all of these factors took a tremendous toll on the Black community. The blues offered a way to articulate that pain, to give voice to the unspoken sorrows that haunted their lives.

Davis delves into the themes of loss and loneliness that permeate the blues tradition. These weren’t just abstract concepts; they were lived realities for many Black women. The loss of loved ones to violence, the loneliness of being ostracized and marginalized, the constant struggle to survive in a hostile environment – these experiences shaped the emotional landscape of the blues. Yet, within that darkness, there was also a profound sense of resilience.

The blues wasn’t just about wallowing in despair; it was about finding a way to move forward, to persevere in the face of adversity. It was about acknowledging the pain, but refusing to be defined by it. It was about finding strength in community, in shared experiences, in the unwavering belief that things could, and would, get better. The blues became a source of solace, a reminder that they were not alone in their struggles, and a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit.

IV. Black Feminism Avant la Lettre: Recognizing the Blues as a Precursor to Contemporary Feminist Thought

Here’s where Davis’s analysis truly shines. She positions the blues as a crucial, yet often overlooked, precursor to contemporary Black feminist thought. These women, singing about their experiences decades before the formal articulation of Black feminist theory, were essentially laying the groundwork for a radical understanding of race, gender, and class oppression.

Think about it: they were challenging the patriarchal structures within their own communities, critiquing the racism of white society, and demanding economic justice long before the term “intersectionality” entered the academic lexicon. They were living and breathing a feminist praxis, using their music to articulate their experiences and challenge the systems that sought to control them. They were, in essence, proto-feminists, forging a path for future generations of Black women to follow.

Davis argues that by recognizing the blues as a form of Black feminist expression, we can gain a deeper understanding of the historical roots of the movement. It allows us to see that Black feminism wasn’t just a product of the 1960s and 70s; it was a movement that had been brewing for centuries, fueled by the experiences of Black women who had been systematically silenced and marginalized. The blues becomes a crucial link in the chain of Black feminist resistance, connecting the past to the present and providing a roadmap for the future.

V. Challenging the Canon: Re-evaluating the Blues and Its Legacy

Davis’s work is a direct challenge to the traditional canon of music history, which often marginalizes or outright ignores the contributions of Black women. She demands that we re-evaluate the blues, not just as a musical genre, but as a crucial site of cultural and political resistance. She forces us to confront the ways in which our understanding of music has been shaped by patriarchal and racist biases.

She also questions the tendency to romanticize or fetishize the blues, to reduce it to a simple expression of suffering without acknowledging its radical potential. She insists that we listen to the blues with a critical ear, paying attention to the nuances of the lyrics, the complexities of the musical arrangements, and the social and political context in which the music was created. She demands that we treat these women as serious artists and intellectuals, not just as entertainers.

By challenging the canon, Davis opens up space for new voices and perspectives. She encourages us to explore the music of other marginalized communities, to listen to the stories of those who have been historically silenced, and to recognize the power of music to challenge injustice and inspire social change. Her work is a call to action, urging us to create a more inclusive and equitable understanding of music history.

VI. Beyond the Blues: Implications for Contemporary Social Justice Movements

The lessons of “Blues Legacies and Black Feminism” extend far beyond the realm of music history. They offer valuable insights for contemporary social justice movements, particularly those focused on issues of race, gender, and class. Davis’s analysis reminds us of the importance of listening to the voices of marginalized communities, of recognizing the intersectionality of oppression, and of using art as a tool for resistance and social change.

The blues women, in their own way, were pioneers of intersectional activism. They understood that their struggles were inextricably linked to their race, their gender, and their class. They challenged the dominant narratives that sought to divide them and used their music to create a sense of solidarity across these lines. Their example serves as a powerful reminder that true liberation requires a collective effort, a willingness to stand in solidarity with all those who are oppressed.

Moreover, Davis’s work highlights the importance of cultural production in social justice movements. The blues, in its time, served as a powerful tool for consciousness-raising, for community building, and for challenging the status quo. Today, music, film, literature, and other forms of art can play a similar role, providing platforms for marginalized voices and inspiring action for social change. We must recognize the power of art to shape public opinion, to challenge dominant narratives, and to create a more just and equitable world.

Ultimately, Angela Davis’s “Blues Legacies and Black Feminism” is more than just a book about the blues. It’s a blueprint for radical social change, a testament to the power of music to inspire resistance, and a celebration of the resilience and creativity of Black women. It’s a gauntlet thrown down, a challenge to reconsider everything we think we know about race, gender, and the transformative power of art. Are you ready to pick it up?

Leave a Comment