Feminism, a sprawling intellectual and sociopolitical behemoth, demands constant interrogation. Its tenets, ever evolving, are best understood through the literature that both fuels and reflects its multifaceted nature. To navigate this labyrinthine discourse, one needs a guide, a curated selection of essential reads that illuminates the historical trajectory, theoretical complexities, and practical applications of feminist thought. Forget your simplistic notions of gender equality; we are diving into the radical depths.

This isn’t about warm fuzzies or polite requests for equal pay. This is about dismantling systemic oppression, challenging patriarchal structures, and reclaiming agency in a world designed to silence us. This is about demanding, not asking. The literature we explore here serves as ammunition in this ongoing struggle.

I. Foundational Texts: The Genesis of Feminist Consciousness

We begin at the beginning, or at least, what is often presented as the beginning. These are the cornerstones, the works that laid the groundwork for subsequent feminist movements. Critically engaging with them allows us to understand the evolution of feminist thought, while also acknowledging its inherent limitations and blind spots.

A. Mary Wollstonecraft’s “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” (1792): A tempestuous broadside against the limitations imposed on women in 18th-century society. Wollstonecraft, with characteristic ferocity, argues for the intellectual and moral equality of women, advocating for education as the key to their liberation. Her emphasis on reason and individual rights, however, can be viewed through the lens of its time, often reflecting the concerns of a specific class and neglecting the experiences of marginalized women. Consider its impact on subsequent suffrage movements and its limitations in addressing intersectional issues.

B. John Stuart Mill’s “The Subjection of Women” (1869): Mill, a utilitarian philosopher, makes a compelling case against the legal and social subordination of women. He argues that such subjugation is not only unjust but also detrimental to societal progress. His partnership with Harriet Taylor Mill significantly shaped his views, yet his perspective remains situated within a patriarchal framework, requiring careful contextualization.

C. Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” (1851): A searing indictment of the exclusion of Black women from mainstream feminist discourse. Truth’s impromptu speech, delivered at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention, challenges the very definition of womanhood, exposing the racial biases inherent in the movement. This serves as a crucial reminder that feminism must be intersectional, acknowledging the diverse experiences of women across racial, class, and other social categories.

II. Second-Wave Feminism: A Radical Reimagining

The second wave, emerging in the 1960s and 70s, brought a renewed focus on women’s liberation, challenging traditional gender roles and demanding control over their own bodies and lives. These texts are characterized by their revolutionary zeal and their willingness to confront deeply entrenched patriarchal structures. Prepare to be challenged.

A. Simone de Beauvoir’s “The Second Sex” (1949): A philosophical tour de force that deconstructs the concept of “woman” as a social construct. Beauvoir’s assertion that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman” revolutionized feminist thought, highlighting the ways in which societal norms and expectations shape female identity. The text’s existentialist framework, while influential, can be dense and requires careful study.

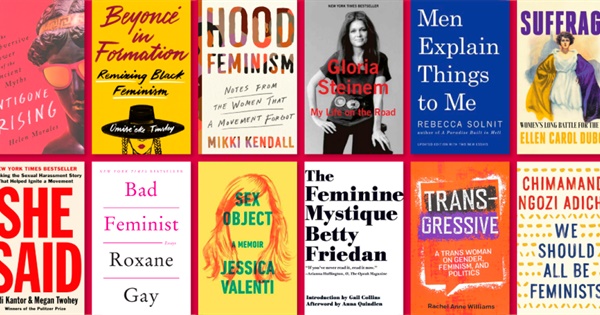

B. Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” (1963): Friedan’s exposé of the “problem that has no name”—the pervasive dissatisfaction of American housewives—sparked a national conversation about women’s roles and aspirations. While her work resonated with many middle-class white women, it has been criticized for its limited scope and its neglect of the experiences of women of color and working-class women. Consider its impact on suburban malaise and its failure to address systemic inequalities.

C. Kate Millett’s “Sexual Politics” (1970): Millett’s groundbreaking analysis of the patriarchal structures embedded in literature and culture offers a scathing critique of male dominance. She examines the works of prominent male writers, revealing the ways in which they perpetuate sexist ideologies. Her interdisciplinary approach, combining literary criticism with political theory, remains influential today.

D. Shulamith Firestone’s “The Dialectic of Sex” (1970): Firestone, a radical feminist, argues that the biological differences between men and women are the root cause of gender inequality. She advocates for technological advancements, such as artificial wombs, to liberate women from the constraints of reproduction. Her ideas, while controversial, challenge us to rethink the very foundations of gender and power. Consider her vision of technological liberation and its potential pitfalls.

III. Third-Wave Feminism and Beyond: Intersectional Perspectives

The third wave, emerging in the 1990s, embraced intersectionality, recognizing that gender is inextricably linked to race, class, sexuality, and other social categories. These texts challenge the essentialist assumptions of earlier feminist movements and celebrate the diversity of female experiences. Get ready for complexity.

A. bell hooks’ “Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism” (1981): A seminal work that critiques the racism and classism within mainstream feminist discourse. hooks argues that feminism must address the specific needs and concerns of Black women, who face multiple forms of oppression. Her work is essential for understanding the complexities of intersectionality and the importance of centering marginalized voices.

B. Judith Butler’s “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity” (1990): Butler’s groundbreaking work challenges the very notion of gender as a fixed and stable category. She argues that gender is performative, meaning that it is constructed through repeated acts and gestures. Her theories have had a profound impact on feminist theory and queer studies.

C. Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses” (1986): Mohanty critiques the ways in which Western feminists often represent Third World women as a homogenous and oppressed group. She argues for a more nuanced and contextualized understanding of women’s experiences across different cultures and regions. This essay is crucial for decolonizing feminist thought and promoting global solidarity.

D. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” (1989): Crenshaw’s article is pivotal in cementing the term intersectionality within legal and feminist circles. It underscores the compounding effect of racial and sexual discrimination experienced by Black women, thereby challenging monolithic feminist and anti-racist approaches. It is essential for understanding how overlapping identities create unique experiences of marginalization.

IV. Contemporary Feminist Voices: Expanding the Dialogue

Contemporary feminist literature reflects the ongoing evolution of feminist thought, addressing issues such as transgender rights, environmental justice, and the impact of social media. These voices are diverse, challenging, and essential for understanding the current state of the movement. Brace yourselves for new perspectives.

A. Roxane Gay’s “Bad Feminist” (2014): Gay’s collection of essays explores the complexities of being a feminist in the 21st century. She candidly discusses her own imperfections and contradictions, challenging the notion of a “perfect” feminist. Her work is relatable, accessible, and encourages critical self-reflection.

B. Rebecca Solnit’s “Men Explain Things to Me” (2014): Solnit’s collection of essays examines the phenomenon of “mansplaining” and other forms of male entitlement. Her work is both humorous and incisive, exposing the subtle ways in which women are often silenced and marginalized in everyday interactions.

C. Laurie Penny’s “Unspeakable Things: Sex, Lies and Revolution” (2014): Penny’s collection of essays explores a wide range of contemporary feminist issues, from online activism to sexual violence. Her writing is provocative, engaging, and challenges readers to confront uncomfortable truths. She examines the complexities of consent, power dynamics, and the impact of technology on feminist activism.

D. Carmen Maria Machado’s “In the Dream House” (2019): Machado’s memoir blends genres to explore the complexities of queer domestic abuse. The narrative employs diverse literary tropes to portray the insidious nature of power and control within intimate relationships, broadening the scope of feminist discourse on violence and identity. Her innovative approach creates a hauntingly introspective and deeply moving experience.

V. Beyond the Canon: Expanding Your Feminist Horizons

While the above texts represent a crucial foundation, feminist literature extends far beyond this curated list. To truly understand the breadth and depth of feminist thought, one must actively seek out diverse voices and perspectives. Dare to explore.

A. Intersectionality in Action: Explore works that delve into the specific experiences of women of color, queer women, disabled women, and women from other marginalized communities. Look for narratives that challenge dominant narratives and offer new perspectives on gender, power, and oppression. Seek out writers like Audre Lorde, Cherríe Moraga, and Patricia Hill Collins.

B. Global Feminisms: Engage with feminist writers from around the world, who offer unique perspectives on gender inequality and social justice. Look for works that challenge Western-centric views of feminism and promote cross-cultural understanding. Explore the writings of Nawal El Saadawi, Vandana Shiva, and Arundhati Roy.

C. Feminist Science Fiction and Fantasy: Explore fictional worlds that challenge traditional gender roles and explore alternative social structures. Authors like Ursula K. Le Guin, Margaret Atwood, and Octavia Butler offer powerful critiques of patriarchy and envision more equitable futures. Immerse yourself in speculative narratives that reimagine gender and power.

D. Zines and Independent Media: Seek out independent feminist publications, zines, and online platforms that provide a space for diverse voices and perspectives. These sources often offer cutting-edge analysis and commentary on current feminist issues, outside of mainstream media outlets. Support independent creators and amplify marginalized voices.

This journey through feminist literature is not a passive endeavor. It requires critical engagement, self-reflection, and a willingness to challenge your own assumptions. Embrace the discomfort, question everything, and join the ongoing struggle for a more just and equitable world. The fight, as always, continues.

Leave a Comment